Mark Twain Slept Here, Or Did He? — Celebrating New York From the Morgan to the Belleclaire

By Stuart Mitchner

Bliss. Feeling like a kid up past his bedtime, I’m stretched out on a cushioned window seat on the ninth floor of a century-old Beaux Arts hotel gazing at the  lights moving up and down after-midnight Broadway.

lights moving up and down after-midnight Broadway.

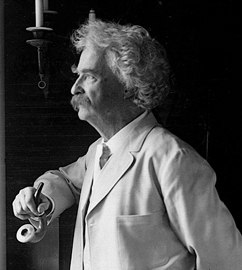

We checked into the Hotel Belleclaire after spending Saturday afternoon at the Morgan Library and Museum’s Gatsby to Garp exhibit of 20th century American literature rarities from the Carter Burden collection. Since one of the Belleclaire’s claims to fame is that Babe Ruth and Mark Twain once stayed there, the hotel offers suites named for the Sultan of Swat and the author of Huckleberry Finn. Asked about the Mark Twain Suite, the man at the desk says, “Somebody already lives there.” After I mention that I’m planning to write a column about our stay, he says the best he can do is an “upgrade.” He and his female co-worker are smiling as they send us up to Room 903, which turns out to be, ta-dum, the Mark Twain Suite, and here he is, large as life, white-maned and white-suited in three framed, hugely enlarged photographic reproductions — wearing a top hat in the entry hall; looking out a window with his pipe in his hand on the wall of the sitting room, along with framed sketches of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer; and seated as if waiting for us in the second room, which has a replica of a vintage bed with cast-iron curtained head board within easy reach of a replica of a Twain-era telephone.

A knock at the door and in comes a man bearing a bottle of Merlot and two wine glasses. A minute later he’s back with two bottles of water and some Dean & DeLucca snacks. On shelves beside the sofa are facsimile first editions of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn and the lavishly illustrated volume that accompanied the Ken Burns American Lives documentary about Mark Twain.

At the Morgan

On days like this New York is in its glory. As we walk crosstown from Penn Station, everything’s falling into place, as if the whole city has achieved clarity, it’s all working, even the balance is balanced, and after sharing an upscale cheeseburger lunch at the Morgan’s courtyard cafe, we’re ready for the Burden exhibit. My wife indulged my craving for a burger and fries without my having to convince her that nothing else on the menu went as well with a visit to 20th century American literature. It’s true that the exhibit begins with Henry James, who most likely would have scorned such an unseemly delicacy (though he did partake of donuts and there’s a photo to prove it). In fact, James is treated as an outlier, an island unto himself in an anteroom, where he’s represented by an American first of Portrait of a Lady; the doomed play he made from his novel, The American; and a post card of a church. James is there because Burden’s collection had its “foundation” in the Master, “the only nineteenth century writer who being an American felt the method of the twentieth century,” according to Gertrude Stein.

Sorry, but if anyone “felt the method ahead of the century” it was New Jersey’s own Stephen Crane, not to mention our roommate Sam Clemens, neither of whom are on the premises. Ask Hemingway about his debt to Crane and he’ll be even more vocal on the subject of the man the Belleclaire named a suite for, witness his declaration in The Green Hills of Africa that “all American literature comes from one book … called Huckleberry Finn.”

No more carping, it’s a fascinating show, and one of the highlights is Hemingway’s expansive, playful, if not downright nutty inscription in The Sun Also Rises. Of course seeing the dust-jacketed first edition of Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby is a thrill; no matter how often you may have seen the cover reproduced, it’s still the most charismatic image in American literature. Other highlights: Fitzgerald’s heavily annotated proof sheet for a Civil War story; the first editions of Dashiell Hammet’s The Maltese Falcon and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, along with the shooting script for The Thin Man and Knopf’s publicity sheet (“In 1929, we gave you Hammett, in 1934 we gave you [James M.] Cain, in 1939 we give you Chandler and The Big Sleep”), not to mention Little Brown’s flyer for The Catcher in the Rye (“This book is going to click!”) and Salinger’s polite letter to a Little Brown copy editor about Franny and Zooey. Of all the letters, the most striking is the long, eloquent, typically selfless and apparently futile one Allen Ginsberg wrote to John Ciardi explaining the art of Jack Kerouac.

Gorky Scandal

Gorky Scandal

For several days I’ve been trying to find out when, why, or how Mark Twain, who had a home of his own on lower Fifth Avenue, ever resided at the Belleclaire. The one piece of evidence I’ve found concerns the Russian novelist, playwright, and revolutionary, Maxim Gorky, who stayed at the hotel in April 1906, presumably at Twain’s urging. The Belleclaire was only three years old at the time and still an architectural showpiece, the first “skyscraper” hotel (it was all of ten stories high).

Gorky’s arrival in America was front page news. A long story in the April 13 New York Times about his adventures in the city (he visited Grant’s Tomb, among other tourist sights), offers the clearest evidence of Twain’s presence at the hotel: “Mark Twain and W. D. Howells called upon Gorky at his apartments in the Hotel Belleclaire last evening. They remained with him for about half an hour discussing literature, and invited him to attend a literary dinner about a fortnight from now.”

The dinner never happened because it was discovered that the charming woman referred to in various news stories as Mrs. Gorky was an actress with whom the writer had been living ever since his separation from his wife a few years before. The press-fueled out-of-wedlock scandal was unacceptable to the Belleclaire’s owner, who evicted the couple and huffily told the Times, “My hotel is a family hotel, and in justice to my other guests I cannot possibly tolerate the presence of any persons whose characters are questioned in the slightest manner.”

After two other hotels turned them away, Gorky and his mistress left the city; he told reporters, “The publication of such a libel is a dishonor to the American press. I am surprised that in a country famed for its love of fair play and reverence for women, such a slander as this should have gained credence.” Only the day before, the Times story had quoted him saying, “This is a wonderful country, surely the Promised Land. I hope I shall live to see the day when things are this way in Russia.”

Later that same year, back in his homeland, Gorky wrote a nightmarish account of “the wonderful country” titled “The City of the Yellow Devil” where the buildings “tower gloomily and drearily,” there are “no flowers at the windows and no children to be seen,” and the city is “a vast jaw with uneven black teeth” breathing “clouds of black smoke into the sky.”

Never the Twain

I have no reason to doubt that Twain himself stayed at the Belleclaire, if only because it was “the thing to do” when the hotel was a unique addition to the city. But since I’ve been unable to pin down an exact time and place, I can only resort to Twain’s own rationale, stated in Eve’s Diary: “If there wasn’t anything to find out, it would be dull. Even trying to find out and not finding out is just as interesting as trying to find out and finding out; and I don’t know but more so.”

Remember this is the author who threatened to prosecute, banish, or shoot persons attempting to find a motive, a moral, or a plot in his most famous novel. As Huck himself says, “there was things” that the author “stretched, but mainly he told the truth.”

It’s also true that “Gatsby to Garp: Modern Masterpieces from the Carter Burden Collection” will be at the Morgan Library and Museum through September 7.