On Scott Fitzgerald’s Birthday: “Some Day You’ll Be Old Enough to Read This”

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Among American writers, my mother favored Scott Fitzgerald, who was born on September 24, 1896, and died December 21, 1940. A hundred years ago this month he was starting his sophomore year at Princeton.

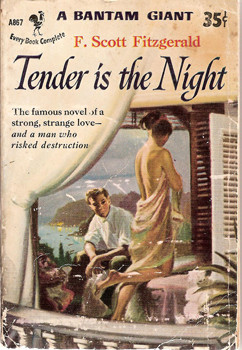

My mother had a small study adjoining my father’s big study, with just room enough for a desk, a chair, and some bookshelves. There were always books around, mostly paperbacks, but the only novel of Fitzgerald’s I remember seeing there was Tender Is the Night, which Scribners first published 80 years ago this spring. The cover of the Bantam paperback caught my adolescent attention because of the woman with the towel draped around everything but her back and legs; the sentence under the title said: “The famous novel of a strong, strange love — and a man who risked destruction.” The man on the cover was looking sideways at the woman, as if he were bored. Outside the window was a painted view meant to be the French Riviera.

“Some day you’ll be old enough to read this,” my mother told me. I figured she meant old enough to comprehend what “strong, strange love” was all about and how a man in such intimate proximity to a half-naked woman could look so bored.

In the Shadow of “Gatsby”

I’ve never really liked Tender Is the Night. Both before and after I was “old enough to read it” I found it scattered, wordy, and full of expendable dialogue, its characters off-putting, as if after all that work, the author himself finally couldn’t find it in his heart to care about them. Reading The Great Gatsby, you know Fitzgerald loves his characters and his creation. My reaction to the later, much longer, more ambitious novel has been somewhat complicated by the fact that there are two versions. In the original 1934 edition, which I first read in the paperback with the sexy cover, the narrative begins on the Riviera in 1925 with a young movie starlet named Rosemary Hoyt. A great deal happens before the novel flashes back to Zurich in 1917 and its true protagonist, Dr. Richard Diver. Pondering the book’s disappointing reception, Fitzgerald began to think that the true beginning was with “the young psychiatrist in Switzerland,” and in 1951, a decade after his death, Scribners published the chronological version of Tender Is the Night “with the author’s revisions” in a single volume with The Great Gatsby and the unfinished Hollywood novel, The Last Tycoon. The critic Malcolm Cowley, who introduced and edited the revision, ends by making a case for the superiority of the chronological version.

All this month I’ve been rereading Tender Is the Night and comparing the chronological revision with the original. I also revisited Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” which provided the title, and read around in The Crack-Up, a posthumous collection of Fitzgerald’s essays, correspondence, and notebooks put together by his friend and Princeton classmate Edmund Wilson. Either way, I find a brave, driven, sprawling, fascinatingly flawed work that anyone who loves Fitzgerald and Gatsby should value the same way readers who love Melville and Moby Dick cherish Pierre, both books written in the shadow of their great predecessors. To begin to fathom what Fitzgerald was up against in the nine years it took him to pull together Tender Is the Night, imagine sitting down to write another novel after producing one that T.S. Eliot called “the first step American fiction has taken since Henry James.”

Then there was the timing. The Great Gatsby arrived at the heart of the era it evoked. Tender Is the Night, with its wealthy, neurotic characters partying and sunning themselves in European settings, was not a good fit for 1934. Fitzgerald had become so much the dated emblem of the roaring twenties, the Depression had no place for him. Not that any of it mattered to mainstream reviewers who had been no less clueless about Gatsby, or to a reading public whose response to that “first step” since Henry James was registered in hugely disappointing sales compared to those of Fitzgerald’s Princeton novel, This Side of Paradise (1920).

Clinical vs. Lyrical

In his appendix to the 1951 revision, after describing the various drafts of Tender Is the Night “kept in six big blue cartons” in the Princeton University Library’s Manuscript Room, Malcolm Cowley finds that they “reveal how an author who was not a born novelist, but rather a romantic poet with a gift for social observation, a highly developed critical sense, and a capacity for taking infinite pains, went about the long task of putting his world into a book.”

Chances are that had the novel achieved acclaim and sales worthy of his expectations, Fitzgerald would have resisted tampering with a narrative form resembling the one he employed in Gatsby, where the romantic poet and socially aware novelist sustain a brilliant balance. The opening paragraph of the revision, with “Doctor Richard Diver arriving in Zurich at 26 (“a fine age for a man, indeed the very acme of bachelorhood”), is flatly expository. In the original version, the misbegotten poet is there from the beginning, with the first paragraph’s image of “the cupolas of a dozen old villas rotted like water lilies among the massed pines.” In the second paragraph, poetry and prose coalesce in a sentence worthy of Gatsby: “The hotel and its bright tan prayer rug of a beach were one.” The poet and novelist connect less smoothly in the description of Rosemary, “who had magic in her pink palms and her cheeks lit to a lovely flame, like the thrilling flush of children after their cold baths in the evening. Her fine forehead sloped gently up to where her hair, bordering it like an armorial shield, burst into lovelocks and waves and curlicues of ash blonde and gold. Her eyes were bright, big, clear, wet, and shining, the color of her cheeks was real, breaking close to the surface from the strong young pump of her heart. Her body hovered delicately on the last edge of childhood — she was almost eighteen, nearly complete, but the dew was still on her.”

Though the poet is clearly present in that passage, the stress on “children after their cold baths” and the “strong young pump of her heart” seems more clinical than lyrical. While it could be interpreted as a suggestion of the doctor’s point of view, the description feels like a formal offering, as if the author were a chef spreading a full course of imagery before the reader.

It gets more complicated if you look at Fitzgerald’s presentation of Dick’s beautiful schizophrenic wife Nicole, who is modeled on Scott’s Zelda. In the original version, you see her first from Rosemary’s point of view, “Her face was hard and lovely and pitiful,” a sentence that reads less like the observation of an 18-year-old starlet than a salute to Hemingway. A few chapters later, a touch of Keats enters the cadence of Rosemary’s impression of Nicole’s beauty: “Her face, the face of a saint, a viking Madonna, shone through the faint motes that snowed across the candlelight, drew down its flush from the wine-colored lanterns in the pine. She was still as still.”

“Verduous Glooms”

One of the few reasons to prefer the revised, chronological beginning is that the moment in the novel where poet and novelist seem truly in harmony comes in the fifth chapter of Book I, rather than many pages later in the fifth chapter of Book 2. Given the almost total absence of poetry in the narrative detailing Dick Diver’s descent into ruin and obscurity, however, it might have been more powerful and poignant for the reader to see Nicole at that point not through the eyes of Rosemary but as Dick does in the ecstasy of falling in love, when her “moving childish smile … was like all the lost youth in the world.”

In view of the novel’s long, ugly, aggressively anti-lyrical denouement, where the “strong, strange love” does indeed destroy the man who “risked destruction,” the lyrical summit of Tender Is the Night, its “Ode to a Nightingale” moment where aura and atmosphere take on the glow of Keat’s “high romance,” is in the scene where Dick and Nicole listen to songs together, “as if this were the exact moment when she was coming from a wood into clear moonlight. The unknown yielded her up; Dick wished she had no background, that she was just a girl lost with no address save the night from which she had come.”

When Nicole sings to Dick, “The thin tunes, holding lost times and future hopes in liaison, twisted upon the Valais night. In the lulls of the phonograph a cricket held the scene together with a single note.” After her song, she smiles at him, “making sure that the smile gathered up everything inside her and directed it toward him, making him a profound promise of herself for so little, for the beat of a response, the assurance of a complimentary vibration in him. Minute by minute the sweetness drained down into her out of the willow trees, out of the dark world.”

Fitzgerald’s shading of the scene evokes the mood of the lines from “Ode to a Nightingale” he uses for an epigraph, “Already with thee! tender is the night …. But here there is no light,/Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown/Through verduous glooms and winding mossy ways.”

Fitzgerald Reading

There’s a posting on YouTube of Fitzgerald reading a portion of “Ode to a Nightingale,” which must have been from memory because there are errors and omissions in nearly every line. So deeply felt is the recitation, however, no one hearing it would quibble. From all accounts, Keats’s poetry was already one of Fitzgerald’s guiding lights when he came to Princeton as a freshman in 1913.

Long ago, around the time I was gawking at the lady on the cover of the paperback, my parents and I drove through nighttime Princeton on the last leg of a two-day drive to New York. As we passed the campus gates, my mother said, “This is where Scott Fitzgerald went to school.” When we walked by the Plaza Hotel a few days later, she told me about Scott and Zelda’s notorious drunken swim in the fountain. A serious drinker herself, she thought of Fitzgerald as a compadre, but it wasn’t the darling of the Jazz Age she felt true kinship with, it was the handsome, greying “has been” who died at 44 in Hollywood making notes on next year’s Princeton football team in his copy of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

The quote about Fitzgerald’s death is based on the account in Andrew Turnbull’s biography.