John Berryman Joins Dylan Thomas in Life and Death: A Double Centenary

By Stuart Mitchner

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

—Dylan Thomas

I was in the corridor, ten feet away.

—John Berryman, when asked about the death of Dylan Thomas

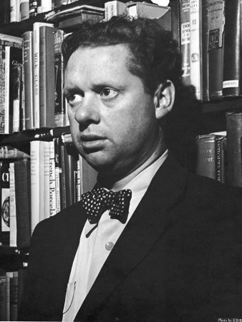

John Berryman and Dylan Thomas were born two days apart, 100 years ago this month, Berryman on October 25, Thomas on October 27.

In Dylan Thomas in America, after a harrowing account of the poet’s last days at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan, John Malcolm Brinnin, who had brought Thomas to the U.S. for a series of readings from 1950 through 1953, describes the moment he received the news he’d been dreading: “As I stepped from the waiting room into the corridor, I saw John Berryman rushing toward me. ‘He’s dead! He’s dead! Where were you?’”

Berryman’s biographer John Haffenden excused the accusatory “Where were you?” as “a manifestation of shock,” but it must have galled Brinnin, who had been faithfully in attendance for four days while Berryman was out of town. There’s a melancholy “poetic justice” in the notion that Berryman, Thomas’s birth-week brother poet, would be there at the end, the first among those who knew him to witness and report the fact of his death. When he had word that Thomas might be dying, Berryman was at Bard College giving a lecture on Shakespeare. According to Haffenden’s 1982 biography, his reaction to the news was “notably dramatic and drunken.” After announcing “Poetry is dead with Dylan Thomas,” he continued “melodramatizing his concern” during a “country walk,” saying, “as he took long gulps of air, ‘I’m breathing for Dylan, if I breathe for him perhaps he will remain alive.’” Another biography, Paul Mariani’s Dream Song (1990) has Berryman drunkenly reciting Thomas’s most quoted poem, “Do not go gentle into that good night.”

Paul Muldoon cites “Do not go gentle” in his introduction to the 2010 reissue of the original edition of Collected Poems (New Directions $14.95), observing that it is “not only vital in itself but also of some value to us in our day-to-day lives” as a poem read “at two out of every three funerals.”

The notion of battling death, so forcefully sounded in the line, “Rage rage against the dying of the light,” is reflected in the move Thomas made at 2 a.m. at the Chelsea Hotel when, after telling the woman he was with that he wanted to die, he came out of a fitful sleep, “suddenly reared up with a fierce look in his eyes,” said he had to have a drink, and hurled himself into the New York night and the White Horse Tavern where he claimed to have downed 18 straight shots of whiskey; as legend has it, that’s what precipitated the fatal coma.

Berryman’s Passage

Some 20 years later, Berryman made his own ungentle move, following the scenario he’d half-seriously outlined in a letter to his wife Eileen in fall 1953, days before Thomas’s death. As related in Dream Song, he imagined himself planning to jump off the George Washington Bridge “by climbing over the rail and staring down into the Hudson River until he became so dizzy he would finally let go.” If his body was recovered, he wanted it planted “as cheaply as possible in Princeton.” The facetious reference at the end gives an idea of his complicated attitude toward the town and university where he’d been living and teaching ever since R.P. Blackmur’s offer of a job in 1946 saved him from teaching Latin and English at a prep school in New Rochelle.

Berryman finally performed his vision of suicide on January 7, 1972, when, as related in Dream Song, he walked along the upper level of the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis, climbed “onto the chest-high metal railing and balanced himself,” and while several students watched, “made a gesture as if waving …. Then he tilted out and let go.”

Princeton Hospital

My thoughts on these two October poets might have taken me somewhere more cheerful than St. Vincent’s had I not been preoccupied with the large building on Witherspoon Street currently being relieved of its outer layer prior to death by demolition. The process is hard to ignore, particularly when it’s taking place within view of my work place parking lot. For days now I’ve been watching the facade of the hospital being stripped of its “skin,” as it’s called, a suggestive term for a building so intimately associated with the human body. It’s likely that someone as familiar with hospitalization as Berryman (for exhaustion, epilepsy, and detoxification) had first-hand knowledge of that building during his turbulent, adulterous, hard-drinking, productive years in Princeton. The man who brought him here, the great poet-critic Blackmur, died in that building in 1965, one among numerous celebrated residents (like Albert Einstein in 1955 and 50 years later George Kennan) who breathed their last in the original structure that has been expanded vertically and horizontally over the years with the help of many fund-raising Fêtes.

Reading at Lake Carnegie

Princeton is where Berryman got to know Saul Bellow, a friendship that began with a walk around Lake Carnegie. After reading the manuscript of Bellow’s breakthrough novel, The Adventures of Augie March (1953), Berryman was inspired to write his own breakthrough work, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet (1956), which Edmund Wilson called “the most distinguished long poem by an American since The Waste Land.” Berryman lived only a few blocks away from the lake and viewed it as an inspirational focal point, going there to recite Mistress Bradstreet to a woman friend he associated with his poem’s heroine. In time Berryman’s struggles with the work led to troubles at home. “As he began to ‘kill off’ his mistress,” Mariani writes, “Berryman seemed to die himself.” From his wife’s perspective, he appeared “at last to be forcing an end to their marriage.”

Dylan Rides the Dinky

It goes without saying that all Princeton’s writers and their wives, friends, lovers, and editors, Bellow, Berryman, Wilson, Blackmur, not to mention William Faulkner, Allen Tate and Caroline Gordon, and John O’Hara, among many others, were familiar with the Dinky and its station. According to Dylan Thomas in America, the bard of Swansea rode to town on the little-train-that-could on two occasions in the early 1950s, first for a reading that led to “a night-long bull session with a congenial crowd of undergraduates,” and most memorably on March 5, 1952, when “a cavalcade of motor-cycled policemen … sirened Dylan to the lecture hall from his late train.”

A Vagrant Vision

Dylan Thomas came to Bloomington, Indiana, in May of 1950, and I have a vivid yet vagrant image of the sweating, red-faced poet declaiming from the balcony of a building near the Indiana University Union, the moated, battlemented castle of my childhood fantasies. My father’s closest friend on the English Department faculty had met Thomas at the Indianapolis airport and driven him the 52 miles to Bloomington, stopping at every bar or tavern along the way.

Listening to Thomas on YouTube reading “A Poem in October” on the birthday we share, it’s easy to believe that I did indeed see him that day intoning the words of a man in his “thirtieth year to heaven,” seeing “so clearly a child’s/Forgotten mornings,” walking through “the twice-told fields of infancy” to “the woods the river and sea/Where a boy/In the listening/Summertime of the dead whispered the truth of his joy.” Listening, eyes closed, there again remembering how his sweating discomfort seemed at such a stark remove from the flow of his reading, “Oh may my heart’s truth/Still be sung/On this high hill in a year’s turning.”

Movies and Events

John Berryman’s centenary is barely on the map (you’d need to go to Minneapolis), although Farrar, Straus and Giroux has published The Heart Is Strange, a new selection of poems edited and introduced by Daniel Swift, along with reissues of Sonnets, 77 Dream Songs and the complete Dream Songs. On the other hand, Thomas, who helped ensure his claim to be the Poet of the Age by dint of those exhausting American tours, is the subject of two films, the BBC’s A Poet in New York and Set Fire to the Stars, which premiered earlier this year at the Edinburgh film festival. John Malcolm Brinnin is a character in both films; not so John Berryman. Perhaps someday someone will bring those two poets together to give the world a glimpse of the “heart’s truth” lived out by two “Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight.”

Dylan Thomas festivals abound, in Swansea, London, and New York, where the Poetry Center has organized “Dylan Thomas in America: A Centennial Exhibition,” and a new production of his radio play Under Milk Wood directed by Michael Sheen. Known best for Frost/Nixon and Masters of Sex, Sheen and five other actors will take the stage in the Kaufmann Concert Hall, where Under Milk Wood had its debut in May 1953, half a year before Dylan Thomas was rushed from the Chelsea Hotel to St. Vincent’s “good night.”