Men of Great Spirit and Fine Feeling: Mr. Ciccolini, Mr. Turner, Mr. Lennon, and Mr. McCartney

By Stuart Mitchner

Have you heard the word is love — Lennon/McCartney, “The Word”

With Valentine’s Day almost upon us, and the Oscars not far behind, I’ve been thinking about love scenes in film, love as a force in classical music, and love in the abstract, as it is, for all purposes, in “The Word,” one of the strangest things the Beatles ever recorded, and one of the best.

In that eerie, relentless, evangelical incantation of a song, John Lennon and Paul McCartney reduce the most used and abused term in popular culture to its word-for-word’s-sake-Gertrude-Stein essence. In the chorus, “Say the word and you’ll be free/Say the word and be like me/Say the word I’m thinking of,” word isn’t sung so much as wailed, and not in any bluesey rock and roll revival sense, but dementedly, despairingly, like the cry of souls lost in a loveless wilderness, or like “woman wailing for her demon lover” in Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan.” The song is driven by a determination to possess that one word/note, a worthy challenge, as McCartney once suggested: “To write a good song with just one note is really very hard. It’s the kind of a thing we’ve wanted to do for some time. We get near it in ‘The Word.’” Lennon, whose go-to-the-marrow voice gives the performance its obsessive edge, says “it’s all about gettin’ smart.” Both admit they were smoking grass when they put it together (“We normally didn’t work while we were smoking,” says Paul), which helps explain the myopic, out-of-time focus on a single element.

Speaking Love

The word is spoken only once, and indirectly at that, in the love scene shared by the painter J.M.W. Turner (Timothy Spall) and his Margate landlady Mrs. Booth (Marion Bailey) in Mike Leigh’s film Mr. Turner, which just opened at the Garden. No need for music, nor any other accompanying emotional stimulants. Spall and Bailey deliver the sequence with the verbally nuanced true-to-life warmth Mike Leigh consistently draws from his actors. Admiring the outline of her profile against the parlor window, Mr. Turner compares the chirpy, not quite homely widow to a statue of Aphrodite, adding “the goddess of love” in case the embarrassed lady is unaware of the fact. After he compares his own face to that of a gargoyle, Mrs. Booth gently reminds him of the folly of those who “fish for compliments,” looks him directly in the eye and firmly, sweetly, tremulously tells him that he is “a man of great spirit and fine feeling,” which are qualities of Turner’s the audience definitely needs to be reminded of at this point in the film. His way of sealing his declaration of love is to tell her, after a long, equally direct look, that she is “a woman of profound beauty.” The landlady’s response, beautiful in itself, is the high point of the film’s most moving performance. When she says she’s “lost for words,” she sounds the last note of a love duet composed by a master — almost the last note, for the scene actually ends with a satisfied noise from Timothy Spall, possibly the most eloquent grunt in his repertoire.

Playing Love

Playing Love

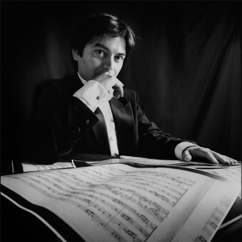

It may be that the proximity of Valentine’s Day had something to do with the BBC’s decision to mark the February 1 death of the renowned pianist Aldo Ciccolini with a video in which he performs “Salut d’Amour,” the piece Edward Elgar composed in July 1888 as an engagement present to his fiancée. Born on August 15, 1925, a month and a half after the passing of Erik Satie, whose piano music he helped bring to life in the 1960s, Ciccolini presents “Salut d’Amour” as if he’d lived and written it himself. Delicately taking creative possession of Elgar’s piece, he seems very much the self-confessed “solitary man” who once said he “should have been born on a desert island” rather than Naples.

Asked in March 2013 why he chose to perform Liszt’s transcription of Wagner’s Liebestod after winning the ICMA (International Classical Music Awards) lifetime achievement award, Ciccolini called the aria “the most beautiful hymn to love ever written …. Many composers have given wonderful expression to love in their music but Isolde’s Liebestod is unique in its sublimity. She becomes reunited with the man she loves …. They are no longer two people, but one.”

Filmed at 87 in a concert performance, his death less than two years away, Ciccolini is seen from above, in mid-range, and close-up, his expression impassive as he channels Liszt and Wagner; his classic Italian profile prompts thoughts of the boy of ten who was “totally transfixed” hearing Tristan for the first time at Teatro San Carlo in Naples and who in his teens interrupted his budding career to play for American soldiers and in bars to help support his family.

Music Is His Love

I found it all but impossible to locate Ciccolini in relation to family or friends or lovers. He never married and, according to the obituaries, left no survivors. A Los Angeles Times interview in March 1986 when he was 61 depicts a devoted, caring teacher allowing a master class to run half an hour past its scheduled conclusion: “Fully absorbed, Ciccolini hovers over the keyboard and later makes a few simple yet profound observations on the interpretive matter at hand.” As for love: “I am more and more in love with music and playing. So I learned to sleep while crossing the Atlantic and to need only three hours a night.” Which gives him that much more time to spend with the love of his life. Move ahead to 2013 and the ICMA interview and he’s talking about “incurable insomnia” and his preference for working at night because “the silence at night is not the same as during the day.” Night is also more forgiving: “one is better disposed and more patient with oneself if everything doesn’t work out as one wishes.”

During the 1986 visit to L.A for an all-Liszt performance at Royce Hall on the 100th anniversary of the composer’s death, Ciccolini scoffed at the journalistic fondness for the idea that he “recorded all of Satie’s piano music and practiced Zen Buddhism and became a French citizen [in 1949].” He expresses no interest in “building popularity,” saying so “with the slightly husky, growling laugh of a Maurice Chevalier,” adding that he “should be a very foolish pianist” to think about “reinforcing” his renown every time he performed: “People will not speak of me in 100 years, but they will still be talking about Liszt. That’s the reality.”

It took a lot of determined searching online to find those few personal details, the Maurice Chevalier laugh, the Zen Buddhism, the philosophical view of his fame next to Liszt’s, and perhaps most interesting, the admission that he “always played what others avoided.”

Ciccolini and Chico

While the proximity of Satie’s exit and Ciccolini’s entrance in the summer of 1925 may not be worth mentioning except as a calendar coincidence, the fact is that Ciccolini’s name became “virtually synonymous with that of Satie,” according to the liner notes to Satie: Great Recordings of the Century (EMI Classics 1986). Listening to Ciccolini playing the first of Satie’s Gymnopédies, so simple and straightforward, you may be reminded, as I was, of the life-walks-on-and-on left hand of Bill Evans’s “Peace Piece.” Listen to the Sports et divertissements, however, and you hear the “intelligent mischievousness” Stravinsky saw in Satie, who composed send-ups of Mozart and Chopin (describing the Funeral March as a “famous mazurka” by Schubert, who never wrote a mazurka), and then in his Embryons desséchés (“Desiccated embryos”), created surrealist fantasies on fossils and crustaceans, including “a sea cucumber that purrs like a cat.”

Though I’ve been unable to find any reference to the other Ciccolini, meaning Harpo and Groucho’s brother, the ever-resourceful character with the same name played by Chico Marx in Duck Soup, you have to believe that the master interpreter of compositions as zany as Satie’s was well aware of Chico and the slapstick sleight of hand he uses to shoot music from the keys like gunfighter counting off shots.

A Day in the Life

Thanks to Ciccolini’s embrace of Satie, we’ve come through Elgar and Wagner and love back to the Beatles, whose groundbreaking recording “A Day in the Life” has some obvious points in common with Satie’s Sonatine bureaucratique, performed by Ciccolini on the Great Recordings album, and accompanied by Satie’s “commentary telling of a day in the life of an office worker.” The Beatles famously end their Day with an orchestral hurricane, a development in their music that may have been first signaled by the chilling, verging-on-atonal chorus of “The Word,” which was recorded in November 1965. Speaking of surrealist fantasies, the title of the album the song eventually appeared on was Rubber Soul, which will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year.

“Everywhere I go I hear it said/In the good and the bad books that I have read,” John sings, then repeats that line in an interview quoted on the site, Beatles Bible — “whatever, wherever, the word is ‘love.’ It seems like the underlying theme to the universe.”