150 Years Later — The President, The Poet, and the Master

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

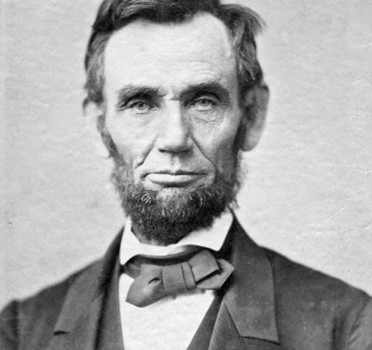

Writing in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, which occurred 150 years ago Tuesday, Walt Whitman refers to the fallen president as “the greatest, best, most characteristic, artistic, moral personality.”

Henry James had just turned 22 on April 15, 1865. According to his biographer Leon Edel, he received the news as “the shrill cry … of an outraged and grieving America standing at the bier of the assassinated president.”

Three months later, in one of his first reviews for the newly founded journal, the Nation, James denounced Whitman’s book of war poems, Drum-Taps, as “an offense against art.” How dare Whitman presume to be the “national poet” only to “discharge the contents” of his “blotting book into the lap of the public?” Although James goes on at length, chiding “the great pretensions” of the stanzas beginning “Shut not your doors to me, proud libraries” and “From Paumanok starting, I fly like a bird,” he ends his review by citing, almost as if in spite of himself, the qualities most famously associated with a poet he would come to appreciate years later — “the vigor of your temperament, the manly independence of your nature, the tenderness of your heart.” As he concludes, James seems to be speaking as much to himself as to Whitman: “You must be possessed, and you must strive to possess your possession. If in your striving you break into divine eloquence, then you are a poet. If the idea which possesses you is the idea of your country’s greatness, then you are a national poet.”

In April 2015, few will dispute Whitman’s claim to be “a national poet,” but who thinks of the expatriate Henry James in those terms? How could that most regal of American writers, who, as Leon Edel puts it, “wielded his pen as if it were a scepter,” be possessed by the idea of the great, sprawling, vulgar country’s “greatness?” Yet when James returns to the U.S. for the first time in 20 years and writes The American Scene (1907), he “possesses his possession” every bit as passionately, expansively, and poetically as Whitman, doing so all the while in a supremely Jamesian manner.

James Asks Directions

In the vaudeville of American history, Lincoln struts his stuff, cracking jokes and quoting Shakespeare, while Whitman gathers the audience to his bosom and does everything but dive into the 19th-century equivalent of the mosh pit. James meanwhile is caricatured in the press during the ten-month visit to the States (1904-1905) recounted in The American Scene. As Edel points out, “Jokes became current in cultured circles about the lady who knew ‘several languages — French, New Thought, and Henry James.’” Then there was “the lady who boasted she could read Henry James ‘in the original.’” Like bloggers today, letter writers to the New York Times sniped about a convoluted style that would “drive a grammarian mad.”

James’s friend, novelist Edith Wharton, recalls his attempt to ask directions upon their arrival late at night in the town of Windsor in her 1904 Pope-Hartford motor-car. As Wharton tells it, James called over an elderly passer-by and proceeded, thus, “My friend, to put it to you in two words, this lady and I have just arrived here from Slough; that is to say, to be more strictly accurate, we have recently passed through Slough on our way here, having actually motored to Windsor from Rye, which was our point of departure; and the darkness having overtaken us, we should be much obliged if you would tell us where we now are in relation, say, to the High Street, which, as you of course know, leads to the Castle, after leaving on the left hand the turn down to the railway station …. In short, my good man, what I want to put to you in a word is this: supposing we have already (as I have reason to think we have) driven past the turn down to the railway station (which in that case, by the way, would probably not have been on our left hand, but on our right), where are we now in relation to — ”

At this point, seeing the confusion on the old man’s face, Wharton loses patience: “Oh, please, do ask him where the King’s Road is.”

“Ah —? The King’s Road? Just so! Quite right! Can you, as a matter of fact, my good man, tell us where, in relation to our present position, the King’s Road exactly is?”

“Ye’re in it.”

Living in Style

Living in Style

James lived his style, whether the situation was formal or casual. Even when felled by a stroke a hundred years ago this December, he told a friend that his first thought was, “So it has come at last — the Distinguished Thing.” He died three months later.

Probably the most frequently cited critic of James’s late prose was his brother William, author of The Varieties of Religious Experience, who in 1907 urged him to “sit down and write a new book, with no twilight or mustiness in the plot, with great vigor and decisiveness in the action …. Say it out, for God’s sake and have done with it! For gleams and innuendoes and felicitous verbal insinuations you are unapproachable, but the core of literature is solid. Give it to us once again!” He contrasted his own manner (“to say a thing in one sentence as straight and explicit as it can be made”) to his younger brother’s determination to “avoid naming it straight, but by dint of breathing and sighing all round and round it, to arouse in the reader … the illusion of a solid object, made wholly out of impalpable materials, air and the prismatic interferences of light, ingeniously focused by mirrors upon empty space.”

Bringing It Off

When William wrote to Henry expressing doubts about his plan to return to America in 1903, advising him of “the sort of physical loathing with which many features of our national life will inspire you,” he provoked a long letter that becomes a manifesto outlining the rationale for the Master’s visit to the land of his birth: “If I shouldn’t, in other words, bring off going to the U.S., it would simply mean giving up, for the remainder of my days, all chance of such experience as is represented by interesting ‘travel’.”

James took eloquent advantage of that experience in The American Scene, where the depth and richness of the prose he lavishes on the “loathed” subject can leave the word-drunk reader reeling. In more than a century of writing about New York City, there is nothing to equal what happens when James takes on the metropolis. As W.H. Auden makes clear in his introduction to the 1946 edition, The American Scene is best read “as a prose poem of the first order,” to be relished “sentence by sentence, for it is no more a guide book than the ‘Ode to a Nightengale’ is an ornithological essay.”

Moral Personality

Moral Personality

In the end, James and Whitman, each in his own way, lived lives worthy of the “the best, most characteristic, artistic, moral personality” that Whitman ascribed to Lincoln on April 16, 1865.

The same term surfaces in Edel’s reference to the “deep affection” James was to develop in later years “for the personality of Whitman,” whose poetry he knew “by heart and on occasion liked to declaim.”

As Whitman writes in his entry on the assassination, “the soldier drops, sinks like a wave — but the ranks of the ocean eternally press on,” so it happens that the 22-year-old reviewer who told Whitman in the Nation that to “sing aright our battles and our glories” it wasn’t enough “to have served in a hospital” finds himself at 70 on the fringes of the Great War visiting wounded Belgian and English soldiers in hospitals, while, according to Edel, likening himself to Walt Whitman during the Civil War. “Friends of the Master wondered how the soldiers reacted to his subtle, leisurely talk,” but what came through was “his kindness, his warmth.” All during 1914 and into 1915 “when illness slowed him up, James surrendered himself to the British soldier.”

Seeing Lincoln Plain

Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., the site of the assassination, is marking the 150th anniversary with a series of programs centered on around-the-clock events, April 14-15. On the street outside, throughout the day and night, living historians will provide first-person accounts about the end of the Civil War, the experience of being inside the theatre at the moment of the assassination, medical reports from the Petersen House, and the impact of Lincoln’s life and death. Starting the evening of April 14, the public will be able to visit the Ford’s Theatre campus throughout the night. The morning of April 15, Ford’s will mark Abraham Lincoln’s death at 7:22 a.m. with a wreath-laying ceremony; church bells will toll across the city, just as they did in 1865.

Also in the news recently is Yale’s acquisition of a major photographic collection featuring “a definitive assemblage of portraits of Abraham Lincoln.” Although Walt Whitman doubted there could be a satisfactory portrait, he tried his hand at a word-picture in summer of 1863: he is “dress’d in plain black, somewhat rusty and dusty, wears a black stiff hat, and looks about as ordinary in attire, &c., as the commonest man …. I see very plainly [his] dark brown face, with the deep-cut lines, the eyes, always to me with a deep latent sadness in the expression …. None of the artists or pictures has caught the deep, though subtle and indirect expression of this man’s face. There is something else there. One of the great portrait painters of two or three centuries ago is needed.”