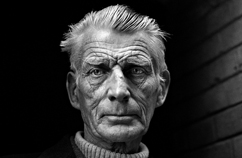

In a New York Moment: Having It Both Ways on Samuel Beckett’s Other Birthday

By Stuart Mitchner

By Stuart Mitchner

Except for the lack of a parking spot on Charlie Parker Place, the transition from Princeton to Manhattan has never been smoother, turnpike to tunnel, uptown, crosstown to a bench in Tompkins Square Park and a sunny spring day of chirping sparrows and grumbling pigeons. While dogs are romping nearby in their own playground, I’m reading about dachsunds “of such length and lowness” that “it makes very little difference to their appearance whether they stand, sit or lie.”

Until I bought the Grove Press paperback of Murphy (1938) last week in Doylestown, I’d never found a way to read Samuel Beckett. In all the English courses I took in college and graduate school, he’d never been on the reading list, no friend had ever chanted his name in my ear, “you must read this,” and I’d never seen a performance of Waiting for Godot. But when I read in Chapter 5 of Murphy that the title character was one of those “who require everything to remind them of something else,” I caught a glimpse of myself in Beckett’s mirror. Of course everything reminds everyone of something, but to require it is another matter and not unlike what I do when I compose a column. Beckett is requiring it in a room where the “lemon of the walls whined like Vermeer’s,” “the unupholstered armchairs” resembled “those killed under him by Balzac,” and the linoleum’s “dim geometry of blue, grey and brown delighted Murphy because it called Braque to his mind.”

Having it Both Ways

After a mere 109 pages of Murphy, Beckett has become a state of mind, a place, a way of life. It’s very Beckett, in fact, that my motive for finally reading and writing about him is based on misinformation about his birth. According to wwnndb.com, he was born on this date, May 13, in 1906. Look elsewhere and the date is April 13. The New York Times obituary of December 27, 1989, has it both ways: “Samuel Barclay Beckett was born in Foxrock, a suburb of Dublin, on Good Friday, April 13, 1906 (that date is sometimes disputed; it is said that on his birth certificate the date is May 13).”

You don’t need to read far in Beckett to appreciate the April/May conundrum. If you have it both ways, or all ways, right or wrong or neither, whether you’re looking for a subject for a column or a New York moment, it becomes possible not only to penetrate what had seemed impenetrable but to see Beckett spilling off the page into the “real life” ambience of dogs and sparrows and people on a spring day in an East Village park.

Enter Nelly and Shelley

As the reader on the park bench in New York resumes reading, Murphy’s title character is in London’s Hyde Park placing five biscuits “face upward on the grass, in order as he felt of edibility … a Ginger, an Osborne, a Digestive, a Petit Beurre and one anonymous.” While he contemplates those items “of which it could be said as truly as of the stars, that one differed from another,” a “corpulent middle-aged woman” asks him if he would mind holding “her little doggy.” Miss Rosie Dew has come all the way from Paddington to feed greens from her garden to “the poor dear sheep” grazing nearby (such was the case in those days). The doggy, a dachsund called Nelly, is, her owner admits, in heat, and Miss Dew is afraid that if Nelly is not held she will “be off and away,” to “plunge the fever of her blood in the Serpentine or in the Long Water for that matter, like Shelley’s first wife you know, her name was Harriet was it not, not Nelly, Shelley, Nelly, oh Nelly how I ADORE you.”

At this moment the reader on the park bench, who has come all the way from Princeton, is grinning as he rereads the passage, with its abrupt, absurd, delightfully rhymingly remindfully blending of Shelley and Nelly. It’s really as if Beckett’s doggy mind has gone for a romp in the park of the page, and Murphy, who “requires everything to remind him of something else,” has found another Romantic poet in the “dingy, close-cropped, undersized and misshapen” sheep that want nothing to do with Miss Dew’s offerings. It’s right about now that the reader is reminded that the author served as James Joyce’s secretary when he was writing Finnegan’s Wake, so is it any wonder that he imagines “a compositor’s error” transforming Wordsworth’s “lovely ‘fields of sleep’” into “‘fields of sheep.’”

Time for a breather after all this chasing after Beckett, who has been cavorting unleashed all over Tompkins Square Park, and we haven’t even come to the first of several denouements, or punch-lines. It seems that while Murphy was engaged by the spectacle of Miss Dew’s “tendering of lettuce” to the dejected, disinterested sheep, the dachsund was eating all the biscuits “with the exception of the Ginger, which cannot have remained in her mouth for more than a couple of seconds.” Murphy thereupon points out to Miss Dew that while “the sheep may not fancy your cabbage … your hot dog has eaten my lunch … or as much of it as she could stomach.” The matter is settled when Miss Dew gives Murphy threepence for “his loss.”

Much more could be said about Miss Dew’s talents as a medium “who could make the dead softsoap the quick in seven languages,” but once you start quoting Beckett you’re lost. As Leslie Fielder notes in a 1997 New York Times appraisal of Murphy, Beckett’s “eerie deadpan humor” involves “the gravely mathematical working out of all the possibilities of the most trivial situation,” for it’s as a “vaudevillian of the avant-garde” that he “especially tickles us, converting its most solemn devices into quite serious gags.” Fiedler finds Murphy the “funniest, perhaps, of his novels,” one that “evokes a ferocity of terror and humor that shames most well-made novels of our time.”

Beckett in Manhattan

In Norman Mailer’s 1958 collection Advertisements for Myself, the excitement generated among New York theatregoers and intellectuals in the spring of 1956 by the Broadway production of Waiting for Godot inspires Mailer to, in effect, jump all over Godot in his column for the Village Voice before, as he admits, either seeing or reading the play. After facetiously congratulating the critics for revealing that the title “has something to do with God,” Mailer points out that Godot “also means ‘ot Dog, or the dog who is hot,” thus “To Dog The Coming, and God Hot for Waiting,” or “Go, Dough! (Go, Life!)” (among “a hundred subsidiary themes”), though in the end he likes “To Dog the Coming” best.

This romp in the dog park of Mailer’s undaunted and ever expanding ego precedes his announcement that a quarrel with the editors of the Voice has made the outburst on Godot his “last column” for the paper “at least under its present policy.”

How rare, how sweet, how very Beckett, that after finally seeing and reading the play and realizing “it was, at the least, very good,” Mailer returns to the Voice long enough to write a mea culpa (“It is never particularly pleasant for me to apologize, and in the present circumstances, I loathe doing so”), which he ceremoniously titles “A Public Notice on Waiting for Godot.” It’s six pages of Mailer throwing everything he’s got at Beckett’s “sad little story, but told purely” — until the character Lucky enters and delivers “the one strangled cry of active meaning in the whole play, a desperate retching pellmell of broken thoughts and intuitive lurches into the nature of man, sex, God, and time” that “comes from a slave, a wretch, who is closer to the divine than any of the other characters.”

Thirteen years later, when the Nobel Committee gave the prize in literature to Beckett, an Irishman who had lived in France most of his life, his French wife said, “This is a catastrophe” while the author of Godot left them waiting in Stockholm and gave away the prize money.

Earth Opera

I’m sitting on the same bench in Tompkins Square Park with my son watching the dogs at play and talking about Earth Opera, one of the great lost groups of the sixties. The words and music from the self-titled debut album had been haunting me for days because the lead singer and lyricist, Peter Rowan, was the first and only person to point me in the direction of Beckett. True to Murphy’s law about requiring everything to remind him of something else, Beckett reminds me of Rowan, who reminds me of watching Earth Opera perform free summer Sunday concerts on the Cambridge Common.

Back from three hours browsing the stock at Academy Records, my son had been hoping to find the first Earth Opera album, which had seen him through some hard times in his late teens. The same record had meant so much to me in my late twenties that I looked up Peter Rowan’s number in the Boston phone book and called him to talk about it. Here was someone whose roots were in bluegrass, who had played with Bill Monroe, and now he was writing Brechtian songs like “Home of the Brave” (“and the war was grand, a glorious parade”), “Death by Fire,” which ends “no willow will weep for her silence of ashes, will sleep in the new fallen snow,” and “Time and Again,” which begins “Every day is the same growing gently insane/it’s the wind or the rain/but I don’t feel anything.” Then there were lines like “and it is being only being, it is as it was before” and “I can see you combing sleep from your hair as you choose what to wear and you whisper who’s there to the mirror on the wall.”

So here I was, a total stranger calling Rowan up like Holden Caulfield calling Fitzgerald after reading Gatsby, asking, in effect, who’s your favorite writer, where did all this come from?

Said Peter Rowan without hesitation, “Beckett. Samuel Beckett.”