Golden Anniversary: In The Beatles Romance, “Yesterday” Is the Good 9/11

Beatles publicist Derek Taylor (1932-1997) begins his preface to Volume 1 of The Beatles Anthology (1994) by contrasting his “rose-colored” view of the group’s worldwide impact — “the Twentieth Century’s greatest romance” — to John Lennon’s typically hard-nosed, “We were just a band who made it very very big.”

Beatles publicist Derek Taylor (1932-1997) begins his preface to Volume 1 of The Beatles Anthology (1994) by contrasting his “rose-colored” view of the group’s worldwide impact — “the Twentieth Century’s greatest romance” — to John Lennon’s typically hard-nosed, “We were just a band who made it very very big.”

Had he been alive in May 2003 and June 2004, Taylor would have witnessed a massive validation of that great romance in the delirious crowds thronging Red Square (est. 100,000) and St. Petersburg’s Palace Square (est. 50,000), waving their arms and dancing and smiling and cheering in ecstasy as the embodiment of the Beatles, Paul McCartney, sang “Hey Jude” (with the crowd joining in) and closed the show with “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” belting out the line, “And Moscow girls make me sing and shout” to the delight of countless singing shouting Moscow girls.

Now consider what was going on in the world when the Beatles made their first recordings 50 years ago this month, keeping in mind the Moscow and St. Petersburg multitudes and especially those among them who had come to cherish the musicians, the music, and even the words, in a language not their own, by taking their chances with records smuggled in from the West. On Tuesday, September 11, 1962, when the Beatles were in the studio recording “Love Me Do” and “Please, Please Me,” the Soviet Union was warning the U.S. that an attack on Soviet ships carrying supplies to Cuba would mean war, Soviet missiles fitted with nuclear warheads having arrived in Cuba on September 8. A month later, after U.S. spy planes obtained photographic evidence of the building of Soviet missile sites, the battle lines were drawn and the world was closer to nuclear war than at any time before or since. The day the crisis was resolved, October 28, a rock group from Liverpool virtually unknown outside the British Isles was making its first major stage appearance at Liverpool’s Empire Theatre, on a bill topped by Little Richard.

9/11/62 vs. 9/11/01

Most people, me definitely included, are susceptible to the significance and power of dates. During the almost nine years I’ve been writing these columns, the day of the month or the year has as often as not given me a subject, a motive, or an inspiration. So here I am balancing on either end of a manichean seesaw two Tuesdays that happened to fall on the eleventh day of September. On the tables of history September 11, 2001 will weigh as heavily as December 7, 1941, and November 22, 1963. According to the depth and weight and dissemination of immeasurable forces like joy and love, truth and light, the group that began life unspectacularly in London 50 years ago, September 11, 1962, “gave more cheer,” as Derek Taylor put it, “than almost anyone else this century.”

The four rockers from Liverpool did a great deal more for the world than cheering it up, regularly testing the limits in EMI’s Abbey Road studio while creating wonders over the next eight years that no one in 1962 could have imagined. On September 11 they recorded their first single, “Love Me Do,” which failed to get beyond 17 on the British charts. Toward the end of the session, they tried out a Roy-Orbison-inspired song by John Lennon that producer George Martin felt “badly needed pepping up.” The next time they returned to the studio, more than two months later, they increased the tempo, tightened the vocals, and after 18 takes produced their breakthrough song, “Please, Please Me.” At the end of the session, Martin told them “You’ve just made your first number one.” It was the first of 15 number ones, in fact.

“Free as a Bird”

Sitting in a Montreal hotel room, picture window curtains parted for a bright-lights night view packed with skyscrapers after the 400-mile drive to the Miracle of the North, I’m putting Volume One of The Beatles Anthology on the disc player, which is mine, all mine, now that my son is asleep. For a golden anniversary column, my plan is to go back to the earliest record, the primal disc cut in 1958 in the living room of a Victorian house on Kensington Avenue in Liverpool. “In Spite Of All the Danger” is a song Paul co-wrote with George Harrison two years before the Quarrymen became the Beatles. The unlikely title, with its hint of dark fate lurking, is the first example of the group’s knack for “being in mystery.”

I’d forgotten that the album devoted to Beatle history begins with a “new” song, “Free As a Bird,” born in 1977 in New York when John made the demo and completed in 1994 when Paul wrote and sang a brilliant bridge (one of the glories of Beatles music are the middle eights). Meanwhile George was moved to perhaps the most spiritual, passionate playing of his life, Ringo having set things in motion with a thunderclap. In the ten years since the break-up, fans all over the world had been wishing and hoping the group of groups would get back together; the invitation from Russia might have done the trick, had John and George lived that long. The haunting “Free As a Bird” video reminds me of the golden period between A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and the White Album (1968) when everything the Beatles touched seemed to fall magically into place. The dreamlike imagery of the video, viewed as by a bird in flight, offers a dark tour, touching, gloomy, whimsical, and portentous, with John’s voice wailing from beyond the grave and the emergency imagery of police lines and wreckage recalling “A Day in the Life” from Sgt. Pepper (“He blew his mind out in a car”) which in turn evokes the Paul-is-dead phenomenon that had everyone looking for ominous messages in the closing seconds of “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “I am the Walrus” with its sampling from Act Four of King Lear, Oswald (Shakespeare’s or Lee Harvey’s, take your pick) moaning, “untimely death.”

“Yesterday”

Paul McCartney turned 70 on June 18 of this year. Wherever he plays, and he’s still at it, he is the Beatles, as he was in Red Square, and in New York in the aftermath of September 11, closing the October 20, 2001 benefit concert he organized for the first responders to September 11, the New York police and fire departments and their families, as well as for the families of those lost in the attacks, and those working in the recovery effort. The star-studded show ended with McCartney singing “Freedom,” which he’d composed for the occasion. “Yesterday” the last song of the Beatles medley, however, had the most visible emotional impact on the audience.

Paul’s “Yesterday” was a major breakthrough in the Beatles romance, charming and converting adults who had been staring with nagging, reluctant, uneasy fascination at the object of the ludicrous “moptop” phenomenon they never imagined they could ever take seriously. I was in the living room with an English family, a middle-aged couple and their neighbors who had been gently teasing me about my fondness for the Beatles. We were watching Paul sing “Yesterday” on the telly. When the song was over, the adults in the room were, literally, speechless, until one said, in a choked voice, “Well, that was quite nice, wasn’t it?”

Watching the faces of the thousands in Red Square as Paul sang his signature song, I thought of the faces of the people at the 9/11 benefit who took the lyrics and the sad melody personally. In Moscow where many in the crowd were singing along in a language they did not know, their eyes were shining not with sorrow but with love. Well, except for Vladimir Putin, who did at least look pleasant. Which is saying something.

Finally, there was the moment in Pula, on the Adriatic coast in Yugoslavia, a country where the people seemed cold and unfriendly, even hostile, at least to a bearded American hitchhiker still coming down to earth after a year in India. Late one night I heard voices in the street, looked out the window and saw a group of boys and girls about my age singing as they walked, serenading anyone who chose to listen. A bit drunkenly perhaps but beautifully, romantically, they were singing “Yesterday.”

In addition to the program notes for The Beatles Anthology, I used Mark Lewisohn’s The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions and William J. Dowlding’s Beatlesongs. “Being in mystery” comes from a letter by John Keats in which he spins the theory of Negative Capability.

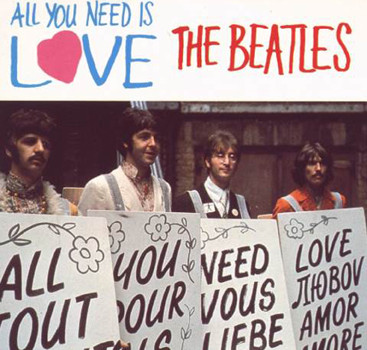

As for Paul McCartney, he will begin his next tour in St. Louis this November. And the French government just awarded the embodiment of the Beatles the Legion of Honor. Cue the Marseillaise opening from “All You Need is Love.”