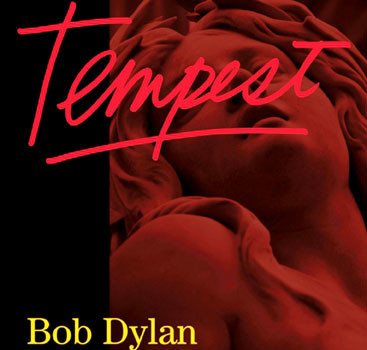

Bob Dylan’s “Tempest” — “Heavy Loaded, Fully Alive and Revved Up”

I wear dark glasses to cover my eyes, there are secrets in ‘em that I can’t disguise…

I wear dark glasses to cover my eyes, there are secrets in ‘em that I can’t disguise…

—Bob Dylan, from Tempest

It was an image for the ages, post-millennium Americana in all its glory at the White House May 29 as President Barack Obama presented the Medal of Freedom to Bob Dylan. Masked behind dark glasses, the 71-year-old with the shadow mustache and air of tenuously contained vehemence (“You’re like a time-bomb in my heart,” he sings in “Duquesne Whistle”) might have stepped from the pages of a story by Flannery O’Connor. When he was called forth to receive his medal, a cheer went up from the overflow East Room crowd. Dylan did not look happy. Not once did he come near to a smile. He was fidgeting like a prize fighter at the ringing of the bell, the president standing by while a disembodied female voice read the inane citation, something about “a voice in the national conversation.”

Tending to the other honorees, including astronaut-senator John Glenn and Nobel-prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison, President Obama had been his usual unflappable self. With Dylan, it was as if he were putting a collar on a pit bull or decorating a land mine. Maybe he’d had a sneak preview of the new album, Tempest, where Dylan growls, “I got dogs could tear you limb from limb,” “I could stone you to death” (“Paid in Blood”); “Ever since the British burned the White House down/There’s a bleeding wound in the heart of town” (“The Narrow Way”); “Then she pierced him to the heart and the blood did flow” (“Tin Angel”); or “I can strip you of life/strip you of breath/ship you down/to the house of death” (“The Early Roman Kings”). In “Long and Wasted Years,” where the singer “can’t disguise” the secrets in his eyes, he warns that “the sun can burn your brains right out.”

As he and Obama shook hands, Dylan gave the president’s arm several little pats, as if to say, no harm done, hang in there, you’re all we got.

His Darkest Work?

No doubt it was Dylan’s idea that Columbia Records release Tempest on September 11, 2012, 50 years to the day that his debut LP Bob Dylan came out. A more curious coincidence is that his highly-acclaimed album, Love and Theft, appeared on September 11, 2001. Paranoid bloggers who suspect Dylan has the devil’s unlisted phone number and may even be his emissary contemplate a satanic conspiracy of wonderful dimensions (throw together the operative words and you’ll find at least one blog debating the issue).

There’s no denying, now more than ever, that Dylan trades in ominous nuances and edgy stalemates, the play of shadows and century-spanning vignettes of gutter romance and violence, of which there are, as I’ve already hinted, a remarkable abundance in the new album. Numerous reviewers think Tempest may be his darkest work ever. In the last chapter of his memoir, Chronicles Volume One, where Dylan’s “little shack in the universe was about to expand into some glorious cathedral, at least in songwriting terms,” he discusses the origins of the tear-your-heart-out dynamic that’s still in force in Tempest. One of the key transformative influences was seeing Brecht on Brecht (with music by Kurt Weill, Brecht’s lyrics translated by Marc Blitzstein) at the Theatre de Lys in the Village in early 1962. Dylan was “aroused right away by the raw intensity of the songs,” “songs with tough language… herky jerky — weird visions” sung by “thieves, scavengers or scallywags” who “roared and snarled.” He mentions “grim surroundings, creepy sensations,” and how “every song seemed to have a pistol in its hip pocket, a club or a brickbat.”

The number that hit him the hardest was “The Black Freighter” or “Pirate Jenny.” After calling it “a wild song. Big medicine in the lyrics. Heavy action spread out,” he writes, “Each phrase comes at you from a ten-foot drop, scuttles across the road and then another one comes like a punch on the chin.” He can’t let it go, still fascinated by what it did to him: “It’s a nasty song, sung by an evil fiend, and when she’s done singing, there’s not a word to say. It leaves you breathless.”

Knowing he’s on to something, Dylan tries to find out “what made the song tick, why it was so effective.” What excites him as a songwriter is that “you couldn’t see what the sum total of all the parts were, not unless you stood way back and waited ‘til the end. It was like Picasso painting Guernica.” Inspired by “Pirate Jenny,” he “began fooling around with things,” taking a lurid story out of the Police Gazette and using Brecht’s song “as a prototype…piled lines on, short bursts of lines.” He liked the idea “but the song didn’t come off.” He was “missing something.” He wastes no time revealing what it was.

When Dylan signed his first contract with Columbia, producer John Hammond gave him an acetate of King of the Delta Blues by Robert Johnson. “From the first note the vibrations from the loudspeaker made my hair stand up,” Dylan writes. “The stabbing sounds from the guitar could almost break a window.” So writes the composer of lines like “Blades are everywhere and they’re breaking my skin” in “The Narrow Way.” When Johnson started singing, he “seemed like a guy who could have sprung from the head of Zeus in full armor.” Six pages later Dylan brings Rimbaud into the mix (“That was a big deal, too…the bells went off”), which “went right along with Johnson’s dark night of the soul” and “the Pirate Jenny framework.” Woody Guthrie’s “hopped up union meeting sermons” are also mentioned, but Dylan’s debt to his mentor is so intimate and respectful that it seems dispassionate by comparison. At this point, five pages from the end of Chronicles, Dylan sets the stage: “I was standing in the gateway. Soon I’d step in heavy loaded, fully alive and revved up.”

The Course of a Lyric

So here he is at 71, with a new album that is undeniably “heavy loaded,” with an event at its center he knew he wanted to write a song about back when he was 20, before he ever made a record. “The madly complicated modern world was something I took little interest in,” he writes in the first chapter of Chronicles. “What was swinging, topical, and up to date for me was stuff like the Titanic sinking.”

In the 45 verses of the title song on Tempest, with its Shakespearean resonance, Dylan is still channeling his early allies, Picasso and Guernica, Rimbaud (“The Drunken Boat”), Robert Johnson (“short punchy verses that resulted in some panoramic story”), and Brecht’s “Black Freighter” while using the Carter Family’s “The Titanic” as his prototype. “I was just fooling with that one night,” he says in an interview with Mikhail Gilmore in the latest Rolling Stone. “I liked that melody — I liked it a lot. ‘Maybe I’m gonna appropriate this melody.’ But where would I go with it?” While he borrows most of the first verse of the Carters’ version and makes good use of the dreaming watchman from the second verse, Dylan’s moon rises not on the ocean but “Out on the Western town.”

Time to set aside the road map and the rule book. If Bob Dylan wants to put the town where it has no business being, like in the middle of the North Atlantic, or vice-versa, that’s his prerogative. “A songwriter doesn’t care about what’s truthful,” he says in the Rolling Stone interview. “What he cares about is what should’ve happened, what could’ve happened. That’s its own kind of truth.” The next 16 verses of “Tempest” are generally true to the historical reality, chandeliers swaying, orchestra playing, smokestack leaning sideways, ship going under, but (with one exception) you won’t find the passengers Dylan mentions on the actual Titanic, although “Leo” and “his sketchbook” (the actor Leonardo diCaprio) were in the James Cameron film. But what about this character Wellington, who was sleeping when “his bed began to slide”? Now he’s strapping on “both his pistols” (“How long could he hold out?”), so it’s that Wellington, and Dylan has cut from April 14, 1912 to the War of 1812. No sooner do you encounter someone who was actually on board (“The rich man Mr. Astor/kissed his darling wife”), then you hear that “Calvin, Blake and Wilson gambled in the dark,” and the Titanic is becoming Desolation Row, with (it seems) John Calvin, William Blake, and (could it be?) Woodrow Wilson joining Wellington and “Davey the brothel keeper” who “came out and dismissed his girls.” Typical of the violence flaring throughout the album, you have brothers on board fighting and slaughtering each other “in a deadly dance.”

Wherever and however Dylan chooses to take it, the ballad’s 45 verses offer the main course in Tempest’s feast of imagery, and 14 minutes on his Titanic is better than 194 on James Cameron’s recently re-released billion-dollar 3-D blockbuster.

“It’s All Good”

Dylan’s band is, as Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie used to say of one another, “the other half of his heartbeat”: Donnie Herron (steel guitar, banjo, mandolin, violin); David Hidalgo (guitar, accordion, violin); guitarists Charlie Sexton and Stu Kimball, drummer George G. Receli, and Tony Garnier’s bass, which at times suggests a lovelorn ghost. The 45 seconds of sunshine leading into “Duquesne Whistle” (co-written with Robert Hunter and released as the album’s single with an accompanying music video) is some of the most sweetly seductive music in all Dylan, and when the drum and bass come pounding in bigtime after the light, melodic spell created by the opening, you feel like the guy in Nash Edgerton’s rough and tumble Chaplin-meets-Tarantino video who can’t help dancing as he playfully stalks the beautiful girl. Look for John Lennon’s face 13 seconds into the video, a subtle acknowledgment of the way he and the Beatles haunt the album, which ends with “Roll On John,” a strong, unsparing elegy for Lennon, who also haunts “Soon After Midnight,” with its subtle echo of the Beatles song “This Boy.”

As for the rest, as Dylan sings on Together Through Life, “It’s all good,” especially “Long and Wasted Years,” the circular motion of life’s wheel of fortune in its gyring guitar; “Scarlet Town” with its sinister “Ain’t Talkin’” ambience; and “Narrow Way,” which swings fiendishly under a killer lyric.

In the Rolling Stone interview, Dylan rightly expresses righteous indignation on the issue of his unacknowledged borrowings. In Desolation Row, there’s room for Wellington and Whittier, Blake and Bo Diddley, and even the city of Vienna, which provided the cover art. The detail shown is from “The Moldau,” one of the four statues in the “Pallas Athena” fountain in front of the Austrian parliament. As I’ve indicated, Dylan has vividly expressed his debt to Brecht, who wrote “The Song of Moldau,” which has a line, claims a blogger from Vienna, that can be translated, “the times they are a changin.”

Last time I checked, the Princeton Record Exchange had restocked discounted copies of Tempest, both regular and deluxe editions.