A Matter of Life and Death: How We Talk When We Talk About Art

Readers of Raymond Carver may recognize the variation on the title story from one of his most famous collections, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Roberta Smith used a version of the same title for a discussion of “the fashionably obtuse language of the art world” four years ago (New York Times December 23, 2007).

Readers of Raymond Carver may recognize the variation on the title story from one of his most famous collections, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Roberta Smith used a version of the same title for a discussion of “the fashionably obtuse language of the art world” four years ago (New York Times December 23, 2007).

In terms of scale, “The Painterly Voice: Bucks County’s Fertile Ground,” which will be at the James A Michener Art Museum through April 1, 2012, is epic, with 200 works by more than 40 artists in three galleries. Curator Brian Peterson’s stated wish is to avoid “stuffy and obscure exhibit labels,” and his casual, person-to-person presentation of this massive exhibit is a refreshing departure from artspeak and the standard curatorial rhetoric, even though he sometimes risks a dumbing down of his subject. After confiding, for example, that from the beginning of his 20 years at the Michener, he’s “dreamed of doing this exhibit,” he ends by reducing “something special” to “a whole heckuva lot of really good paintings.” In his well-meaning attempt at down-to-earth diction, the curator inadvertently brings to mind George W. Bush’s notorious backslap to the incompetent FEMA chief after the debacle of Katrina (“Heckuva job, Brownie”).

The Show Online

Doing anything like full justice to a show of this scope is impossible. That’s why the Michener has put a large portion of the exhibit online, complete with commentaries and a world of information and imagery (http://www.michenermuseum.org/catalogue/painterly-voice). At the museum, QR codes are available for scanning.

The online format makes possible another look at some of the works that held me when I was there in person, including highlights from previous shows, such as Robert Spencer’s cityscapes, and Harry Leith-Ross’s Nightfall on Union Street and The Fair. One piece that kept me gazing beyond a minute was Goldie Peacock’s House, an oil on canvas from 1935 by Charles Ward (1900-1962). In its free-form feeling and sense of fun, it stands apart. There’s no reason why talking about this work shouldn’t be fun as well, and Mr. Peterson catches the spirit of the piece by citing George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” (“those buildings are dancing, the trees are dancing, with each other, with themselves”).

Garber’s Light

If any single artist is the star of this show, it’s Daniel Garber (1880-1958), who was born in Indiana and studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of The Fine Arts and in Europe before settling down a few miles north of New Hope in Lumberville. The work that opens the exhibit is Garber’s 1935 painting of his mentor and colleague, Bucks County artist William Langson Lathrop (1859-1938). Also given a prominent place and featured on the cover of the museum’s Guide to Events and Programs is Garber’s 1915 portrait of his nine-year-old daughter Tanis.

“Light is the first of painters. There is no object so foul that intense light will not make it beautiful.” Although these lines from Emerson are in the commentary accompanying Garber’s landscape, Willows – Noonday (1955), they are even more applicable to what the painter does with the interiors featuring his wife and daughter. Works like Tanis (1915) test the notion of “what we talk about when we talk about art.” How do you react to the blatant beauty of this image of a lovely child wrapped in a sort of diaphanous cloud while spring explodes around her with a brilliance that is almost painful to contemplate? The curator chooses to talk in vivid extremes, “her hair and blouse are lit up like fiery spotlights, as if their very molecules are on fire,” as if “a fairy has touched them with a magic wand …. This is the morning of the day the world was born [Peterson’s italics].”

The curator’s enthusiasm is understandable. It’s a stunning painting. Keeping the notion of talking about art in mind, I emailed the image, along with the other Garbers, to a friend I thought might enjoy seeing them. I made my own feelings abundantly clear (“The way he uses light is amazing!”), assuming she would feel the same way. Not a chance. “It’s a little twee for me, if you know what I mean” was her response to Tanis. If we’d been standing together in front of the painting, I might have tried to downgrade or justify my use of “amazing” by admitting that I felt sympathetic to the idea of the painter’s child, who was born in Paris, died a resident of Bucks County in 1990, and can be seen as a 17-year-old beauty in Garber’s serenely lovely Morning Light, Interior (1923). I might also have admitted that while “twee” wasn’t the word I’d have used, I could see a commercial touch in the soft, smooth, cleanly lighted image that gave it the overtones of a Maxfield Parrish illustration in a story book.

When we talk about art, we’re often talking outside or beyond or beneath it. How important is what we say? What difference does it make? And in the face of great art, what can be said that doesn’t sound either simplistic (“Wow, that’s amazing!”) or pompous? People conversing in the presence of the work will often temper their opinions for the sake of being agreeable, however much they may disagree. Or they may have other things on their mind. The day I was at the Michener most of the talk was not about the art but the effects of the previous weekend’s freak October snow storm. As I admired Garber’s The Studio Wall (1914), which my friend liked, too, someone was talking about the power outage. They were still without electricity and I was thinking, “Here’s power! Here’s electricity!” The Studio Wall is pure enchantment: the sunny day delicately reflected in muted tones of lilac and yellow, the classic beauty of the pose struck by Garber’s wife as she holds a small vase while wearing a vision in the guise of a kimono. Voice or no voice, the painting speaks in colors and images and effects, a form of communication that bypasses language, goes straight to the senses, and stops the conversation cold.

The Human Touch

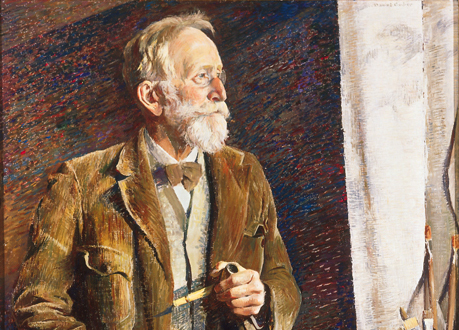

In Daniel Garber’s painting of his mentor and colleague William Langson Lathrop, completed three years before Lathrop’s death in 1938, Lathrop is shown standing at close range, holding a pipe, his other hand thrust in the pocket of a comfortably lived-in looking jacket burnished in shades of brown and reddish gold somewhat like the hues in the forest floor of Lathrop’s work, The Forest (1918). In fact, the elderly painter might be dressed in one of his own land- or sky-scapes, his vest a field of flowers touched with the pearly pastel light of the sky in Evening Before the Storm (ca. 1898), his trousers showing the mottled pastel shades of the sky in Burning Fields, Bucks County (1898). Blazing behind the handsome, white-bearded man with the faraway look in his eyes is a wild, dark, free-form background, streaked and shot with vivid skeins of purple, orange, and red as intense as a nocturnal psychodrama out of Van Gogh.

Garber’s mastery of light, so brilliantly expressed in the paintings centered on his daughter and wife, becomes a subtle secondary presence in the portrait of Lathrop, touching the hand holding the pipe, the sleeve, the pocket of the coat, and as if attracted by the quiet thoughtful intensity of Lathrop’s gaze, the face, the white beard, the hair, and, the deepest, most telling touch, the faint semblance of light on his forehead. Stand in front of this work long enough and it’s possible to imagine that the man’s spirit, his thought, his art, his humanity, his vulnerability, everything he is, has been serenely, definitively illuminated. But then, as if to counter all that lofty verbiage, you have Lathrop’s nose, which appears to be inflamed, irritated, perhaps from a cold, a rash, the rubbing of a pair of spectacles. That suggestion of inflamed flesh is a deterrent to aesthetic overstatement. It says, “Keep things real, on the human level, where noses are blown, eyes get rheumy, and knuckles chapped, and where a pipe, like a paintbrush, can be an old friend.”

A Note on the Curator

Brian Peterson makes his priorities clear at the outset by invoking artist Marianne Werefkin’s observation as the epigraph for “The Painterly Voice,” (“There is no history of art — there is the history of artists”) and by placing Garbers’s painting of Lathrop at the entrance of the show. Curious to know a bit more about the chief curator at the James A. Michener Art Museum, I came upon some information I think is worth sharing. Four years ago, Mr. Peterson was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. In addition to putting together this magnum opus of Bucks County art, and coming to terms with a devastating illness, he’s published a memoir, The Blossoming of the World: Essays and Images, illustrated with his own photographs.

Note: I’ve never dedicated a column to anyone until now. In one sense, every piece I write is dedicated to an ideal reader or readers, and one of my ideal readers was Everett Dale Gross, the contractor who for all purposes rebuilt the interior of the house we’ve been living in since 1986. Though he was known to most of his longtime customers and friends as Dale, we have always called him Everett. Of all the people I know, writers, poets and academics, doctors, lawyers, and librarians, this rugged Vermonter came closest to actually speaking in the direct, down to earth, no-nonsense voice Curator Brian Peterson seems to be striving for in his commentary. Everett died last week at 80, and I know we aren’t the only homeowners in Mercer County who are living in and appreciating every day of our lives the interior he built. All the moldings, doors, bookcases, closets, from the frames on the windows to the tiles on the kitchen floor are due to his handiwork, works of his straightforward art.