Pity, Terror, and Tragedy Within and Without James Joyce’s “Portrait”

By Stuart Mitchner

In the final chapter of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man (1916), Stephen Dedalus tells two of his fellow students what happened to a girl who got into a hansom cab “a few days ago” in London. “She was on her way to meet her mother whom she had not seen for many years. At the corner of a street the shaft of a lorry shivered the window of the hansom in the shape of a star. A long fine needle of the shivered glass pierced her heart. She died on the instant.”

In the final chapter of James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man (1916), Stephen Dedalus tells two of his fellow students what happened to a girl who got into a hansom cab “a few days ago” in London. “She was on her way to meet her mother whom she had not seen for many years. At the corner of a street the shaft of a lorry shivered the window of the hansom in the shape of a star. A long fine needle of the shivered glass pierced her heart. She died on the instant.”

Reading Portrait my senior year in college, I put a ballpoint asterisk next to the anecdote in the Viking Compass paperback (“copyright renewed in 1944 by Nora Joyce”) and above it scrawled the words “accidental causation,” which were probably cribbed from something the teacher said. Although I underlined Stephen’s prosy remarks on “pity” and “terror,” delivered as he explained why it was not “a tragic death,” all that stayed with me was the girl in the hansom cab and the style Joyce had devoted to the brutal, uncanny happenstance of the event, the “shape of a star” and the “fine needle of shivered glass” he employed to finesse a freak accident. Pity, terror, and “the tragic emotion” were secondary; all it finally came down to was the way Joyce had composed it.

It Killed Me

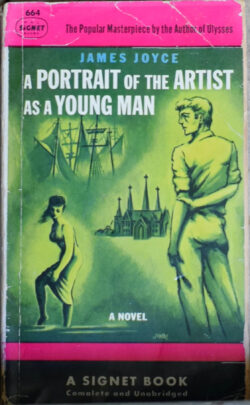

I was Holden Caulfield’s age when I first read Joyce’s Portrait in my mother’s Signet paperback, the one with a photo of an eyepatched Joyce looking like a pirate on the back. Although I was beginning to think of myself as a “young artist” at the time, having composed a series of e.e. cummings travesties, my response to Joyce’s novel was 100 percent Holden: “It killed me.” The moocow coming down the road-and-nicens baby tuckoo opening; the schoolboy at play scenes; the hair-raising sermon; the descent into Dublin’s red light district; and the vision of the girl on the strand — they all killed me. Except, the sermon about hell and eternity didn’t kill me; it terrified me. And the vision of the girl, under which I scribbled “the epiphany!” I was sure it had changed my life. It was my epiphany, even though I thought the part where Stephen’s “soul” cried “Heavenly God!” in “an outburst of profane joy” sounded, well, pretty damn phoney.

As for the fifth and last chapter, what can I say? All that talk about Aristotle and Aquinas, aesthetic theory and Roman history — to me it sounded only a step above the phonies raving about the Lunts that Holden endured when he took Sally to the theater. The one thing that got me and shook me and followed me around for years was the dead girl in the hackney. Why?

Because it came while I was still blissed out over the girl on the strand, who “stood before him in midstream, alone and still, gazing out to sea. She seemed like one whom magic had changed into the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird. Her long slender bare legs were delicate as a crane’s and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. Her thighs, fuller and softhued as ivory, were bared almost to the hips where the white fringes of her drawers were like feathering of soft white down. Her slateblue skirts were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her. Her bosom was as a bird’s, soft and slight, slight and soft as the breast of some darkplumaged dove. But her long fair hair was girlish: and girlish, and touched with the wonder of mortal beauty, her face.”

I was going to condense the part about her thighs and her drawers and the “darkplumaged dove,” but it would have been a violation of the original moment: “Long, long she suffered his gaze and then quietly withdrew her eyes from his and bent them towards the stream, gently stirring the water with her foot hither and thither. The first faint noise of gently moving water broke the silence, low and faint and whispering, faint as the bells of sleep; hither and thither, hither and thither; and a faint flame trembled on her cheek.”

By then I was okay with “the outburst of profane joy,” and how “His soul was swooning into some new world, fantastic, dim, uncertain as under sea, traversed by cloudy shapes and beings.”

Reading the passage now, I’m there again, and it still kills me.

Discoveries

Almost 11 months into 2024 and only now do I realize how Joycean a year it is, all the fours in play, the most obvious being the day Joyce met Nora, June 16, 1904, Bloomsday in Ulysses, then Dubliners in 1914, and of course Nora’s copyrighted 1944 edition of Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man. Plus this is the centenary of the first English (Jonathan Cape) edition, published in 1924.

Portrait surprised me. My only intention had been to write about the girl in the hackney in relation to the movie theatre catastrophes I’d discovered when I looked up today’s date, October 23, in Wikipedia’s list “Events 1901-present,” and found the real-life horror, freak accidents, pity, terror, and tragedy that actually set this column in motion. Given the approach of Halloween and a monstrously fateful Election Day, I was going begin with The Thing, the original 1951 version, which I saw when I was 12 and had never heard of James Joyce or, for that matter, Howard Hawks, who I later came to admire as one of Hollywood’s greatest filmmakers.

Like the vision of eternity and hell in Portrait, The Thing haunted me for years, the impact of that first and only viewing heightened by the screaming of the matinee audience (mostly kids my age), which actually reached such a pitch that the projectionist stopped the film. I wasn’t screaming. I didn’t have to be. Surrounded by so much sheer sonic turbulence, it was as if I was being screamed. In fact, the appearance of the projectionist himself was as shocking as the monster because I could see him looming hugely, alarmingly, outside the projection booth, as if the noise had driven him mad.

“The Wages of Virtue”

The last of the epigrams prefacing Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray is “All art is quite useless,” which follows from “The only excuse for making a useless thing is that one admires it intensely.” Before that, Wilde says “No artist is ever morbid. The artist can express everything. Thought and language are to the artist instruments of an art. Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art.”

On October 23, 1927, at the Imatra cinema in Tampere, the third largest city in Finland, a Gloria Swanson film called The Wages of Virtue was playing. Mordaunt Hall’s New York Times review describes Swanson as “lithe and vivacious, with swiftly changing moods” in the part of Carmelita, the girl who mothers the regiment of gruff soldiers and in a dilettante manner presides over a café, to which the nondescript volunteers come to forget their disappointments or misdeeds with a cheering glass of cheap wine.”

About 200 people were in the audience at the Imatra when the nitrate film ignited. The projectionist, who was 18, tried to extinguish the burning film, but the hot gases exploded, blowing him out of the projection booth, allowing the fire to spread and destroy the building, killing 21 people and injuring 28. The idea of the teenage projectionist burned alive in a freak accident that destroyed a theatre and incinerated 21 human beings brings to mind the girl killed in the London hackney, whose death according to Stephen Dedalus was not “tragic,” that being “the feeling which arrests the mind in the presence of whatsoever is grave and constant in human sufferings and unites it with the secret cause.” In the cinema fire, the un-secret cause was the combustible nature of nitrate film stock. That the community of Tamare considered the event a tragedy is underscored by the fact the over 20,000 people came to the funeral of the victims.

The “Saddest Fire”

After typing a few words online, I came up with the “Saddest Fire” at the Laurier Palace cinema in Montreal, which happened nine months earlier on January 9, 1927, as a matinee audience, almost all of them under 16, was watching a short slapstick feature starring Stan Laurel. This time the actual cause of the fire was never officially determined beyond the fact that it was not caused by a nitrate explosion but more likely by a lighted cigarette tossed on to the floor of the balcony. The death toll was 78 grade schoolers and teenagers, an audience like the one I was part of when I saw The Thing. The title of the film was Get ‘Em Young, which burns with a fiendish irony, all the more because it has nothing to do with the plot: a man and his butler and the man’s wild attempt to marry someone in time to satisfy the provisions of a million dollar will. While there are lots of rough and tumble gags throughout (that old standby seasick passengers on a storm-tossed ship), the funniest scene by far is the denouement in which Stan Laurel ends up reluctantly, drunkenly posing as the bride, which involves being forcibly encased in a bridal gown by the groom. The scene would have prompted screams of laughter if the half-hour-long film had ever reached that point. Get ‘Em Young can be seen on YouTube. The Wages of Virtue is now considered “a lost film.”

The Fifth of November

And so we stagger toward Halloween and the Fifth of November, the date John Lennon cries out at the climax of his primal-therapy-inspired song “Remember,” followed by the sound of an explosion, a reference to Guy Fawkes Night, which is celebrated with fireworks and bonfires. In Lennon’s Rolling Stone interview posted on September 7, 2007, it amused him to suggest the song successfully accomplished a failed plot to blow up the Houses of Parliament.