On Lincoln’s Birthday: Lights and Shadows, Sandburg, Shakespeare, and Black History

By Stuart Mitchner

Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect.” With these words the poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg began his address to a joint session of Congress on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, February 12, 1959.

Not often in the story of mankind does a man arrive on earth who is both steel and velvet, who is as hard as rock and soft as drifting fog, who holds in his heart and mind the paradox of terrible storm and peace unspeakable and perfect.” With these words the poet and Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg began his address to a joint session of Congress on the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, February 12, 1959.

Sandburg made sure to mention some hard truths up front, including the fact that early in his administration, Lincoln “took to himself the powers of a dictator.” As commander of “the most powerful armies till then assembled in modern warfare,” he “enforced conscription of soldiers for the first time in American history. Under imperative necessity he abolished the right of habeas corpus. He directed politically and spiritually the wild, massive, turbulent forces let loose in civil war.” And after failing to get action on compensated emancipation, “he issued the paper by which he declared the slaves to be free under ‘military necessity.’ In the end nearly $4 million worth of property was taken away from those who were legal owners of it, property confiscated, wiped out as by fire and turned to ashes, at his instigation and executive direction.”

On a key date in Black History Month, whether you’re thinking 1959 or 2025, it’s striking to hear emancipated human beings referred to as “property confiscated.” No less striking is the idea of a poet addressing a joint session of Congress in the same room that would be overrun by a lawless (recently “emancipated”) mob during the January 6, 2021 insurrection.

It’s almost as if by opening with the “powers of a dictator” idea, Sandburg somehow anticipated the “turbulent forces let loose” in January 2025 by the newly elected president. As Sandburg makes clear, while Lincoln’s use of these powers, primarily during his first three weeks in office, was urgent and necessary, his ultimate goal was to bring the country together, not to pull it apart. Compare Sandburg’s vision of an abiding leader (who once admitted “I have been controlled by events”) to the president who recently ordered the U.S. Treasury to stop minting the Lincoln penny (among many more consequential dictates): “In the mixed shame and blame of the immense wrongs of two crashing civilizations, often with nothing to say, he said nothing, slept not at all, and on occasions he was seen to weep in a way that made weeping appropriate, decent, majestic.” And even as “the war winds howled, he insisted that the Mississippi was one river meant to belong to one country, that railroad connection from coast to coast must be pushed through and the Union Pacific Railroad made a reality.”

And perhaps most striking of all is the poet’s pondering of the word “democracy” in regard to people of “many other countries” who “take Lincoln now for their own. He belongs to them …. He had something they would like to see spread everywhere over the world. Democracy? We can’t find words to say exactly what it is, but he had it. In his blood and bones he carried it. In the breath of his speeches and writings it is there…. He had the idea. It’s there in the lights and shadows of his personality, a mystery that can be lived but never fully spoken in words.”

Knowing Shakespeare

Sandburg’s phrasing on Lincoln’s mystery, his “lights and shadows,” brings to mind the president’s fondness for Shakespeare, whose words were also in “his blood and bones” along with democracy. It wasn’t just that he could recite long passages from Hamlet and Macbeth and Richard III, he actually knew when the speeches he loved had been violated or omitted, as was sometimes the case with the fratricidal king’s soliloquy in Hamlet or the time when the earthy duel of invective between Falstaff and Hal in the first part of Henry IV was dropped altogether, as happened during a performance the president attended at the Washington Theatre in March 1863.

Lincoln’s enlightened grasp of the plays is evident in his letter to the actor James H. Hackett, who had played Falstaff in that compromised staging of Henry IV. After complimenting Hackett’s performance (“I am very anxious to see it again”), Lincoln refers to his favorite plays, with Macbeth the most admired (“It is wonderful”), before making a distinction between two soliloquies, declaring that the one spoken by Claudius (“O, my offence is rank”) “surpasses” Hamlet’s “To Be Or Not To Be.”

John Wilkes Booth himself might have been struck by that choice, as would perhaps his brother Edwin, the most acclaimed Shakespearean actor of the day. While “To Be Or Not To be” may have more in common with Lincoln’s “philosophy,” it’s important to note that he’s pondering Claudius’s words (“It hath the primal eldest curse upon’t, / A brother’s murder!”) while planning his speech for the dedication of the Gettysburg national cemetery later that month. With the country embroiled in civil war, “brother slaying brother” (including one instance Lincoln had firsthand knowledge of), it makes sense that he’d be more responsive to the grimly timely “My offence is rank” soliloquy, with its reference to a hand “thicker than itself with brother’s blood,” and to the question, “Is there not rain enough in the sweet heavens to wash it white as snow?”

The Shakespearean resonance of Claudius’s words is particularly striking on February 12, 2025, in lines like “May one be pardon’d and retain the offence? / In the corrupted currents of this world / Offence’s gilded hand may shove by justice; / And oft ‘tis seen the wicked prize itself / Buys out the law: but ‘tis not so above: / There is no shuffling, there the action lies.”

Paging Darwin

Aware of the fact that Lincoln and the author of The Origin of Species were both born on February 12, 1809, and given my weakness for the poetry of connections, I recently read “Darwin on Lincoln and Vice Versa,” a January 22, 2009 article in Smithsonian Magazine, in which Lincoln’s law partner and biographer William Herndon refers to the future president’s fascination with Robert Chambers’s Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (published anonymously in 1844), suggesting that Lincoln was “deeply impressed” by the “universal law of evolution,” having told him one day, “There are no accidents in my philosophy. Every effect must have its cause. The past is the cause of the present, and the present will be the cause of the future. All these are links in the endless chain stretching from the finite to the infinite.”

That’s a very “written” statement, but whether Herndon took it down as spoken or finessed it, Lincoln’s presence is signified by his assumption of Hamlet’s most quoted line, to his dear friend Horatio, “There are more things on heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

As for Darwin’s view of Lincoln, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin (Dover paperback) includes a letter to an abolitionist friend in America written a few weeks after the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863: “Well, your President has issued his fiat against Slavery — God grant it may have some effect.” After mentioning his “gloomy view about your future,” Darwin says “I look to your money depreciating so much that there will be mutiny with your soldiers & quarrels between the different states which are to pay. In short anarchy & then the South & Slavery will be triumphant. But I hope my dismal prophecies will be as utterly wrong as most of my other prophecies have been. But everyone’s prophecies have been wrong; those of your Government as wrong as any. — It is a cruel evil to the whole world; I hope that you may prove right & good come out of it.”

Lincolnesque

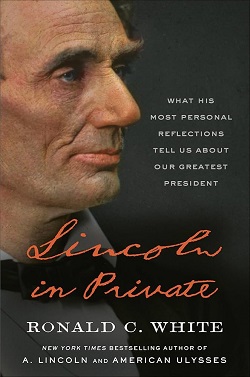

There’s a Lincolnesque story behind the clean-shaven, colorized face on the cover of Ronald C. White’s Lincoln in Private (Random House 2021). As White points out, Lincoln told the photographer Alexander Hesler “that he did not know why people wanted photos of such a homely face. When Hesler insisted on smoothing out Lincoln’s hair,” the future president ran his fingers vigorously through it before sitting, with wild and wonderful results, which the book’s jacket designer understandably cropped, giving Hesler what he wanted a century and a half after the fact.

Black History

February 12 is a date to be reckoned with. Lincoln’s centenary was the occasion of the founding of the NAACP, inspired by the 1908 race riot in his hometown, Springfield, Illinois. Two world wars later on February 12, 1946, an honorably discharged Army veteran named Isaac Woodward was beaten blind by South Carolina police, an atrocity that helped galvanize the civil rights movement.