|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 17

|

|

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

|

|

|

“They’re not here now so I feel like I’m sort of representing all of them, all of the guys. Remember, I’m one of the last guys left, as I’m constantly being told, so I feel a holy obligation sometimes to evoke these people.”Sonny Rollins

The quote is taken from the official Sonny Rollins website (www.sonnyrollins.com), which reports that the legendary tenor man will be in New Brunswick next month receiving an honorary degree in Fine Arts from Rutgers University. The first time he was so honored, at Tufts University, he referred in his acceptance speech to the fact that honorary degrees were not bestowed on jazz musicians back in the days when he idolized “pioneering tenor players” like Don Byas and Lucky Thompson who were “setting up the music” for him. “Accepting the award that night,” he recalled, “I wanted to share it with those who really deserved it. And that’s the same way I feel now.”

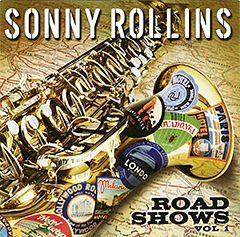

Rollins does more than share honors with his peers and his mentors: he plays for them, channeling tributes into soaring solos like the one I heard him deliver outdoors one hot summer evening around ten years ago at Lincoln Center. His music covered the world of nations and the world of jazz that night — you could hear India, Africa, Harlem, New Orleans, St. Thomas, Constantinople, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Wardell Gray, Dexter Gordon, Ben Webster, Lester Young, the abovementioned pioneers, among many others. Right now no one else on the planet so formidably embodies the glory of jazz. His latest album, Road Shows Vol. 1 (Doxy $14.98), reflects the global scope of his appeal with live performances before large, enthusiastic audiences in British Columbia, Poland, Japan, France, and Sweden. The concluding number, a one-for-the-books rendition of “Some Enchanted Evening” featuring virtuoso playing by bassist Christian McBride, was recorded in 2007 on the 50th Anniversary of his first Carnegie Hall concert.

Flashback: Spring 1959

Fifty years ago this spring saw the appearance of Sonny Rollins with the Contemporary Leaders, the last album he made before his self-imposed exile from the recording scene. Although he was out of action the better part of three years, his fabled practice sessions on the Williamsburg Bridge did wonders for the Rollins mystique. The vision of the Saxophone Colossus blowing tenor from a mid-span perch above the East River has to be one of the jazz century’s central images.

The Princeton Public Library has an excellent selection of Sonny Rollins CDs, although Sonny Rollins with the Contemporary Leaders is not at present among them; the Original Jazz Masters CD is available online and as part of the Freelance Years box set of the Riverside and Contemporary recordings. Road Shows Vol. 1 is at the Princeton Record Exchange. April, by the way, is the Smithsonian’s Jazz Appreciation month, which Cape May celebrated with its 31st jazzfestival.

So named because they recorded for L.A.-based Contemporary Records, the Contemporary Leaders were guitarist Barney Kessel, bassist Leroy Vinnegar, drummer Shelly Manne, and on piano the inimitable Hampton Hawes, whose inspired playing helps make Contemporary Leaders a worthy sequel to Rollins’s other, more celebrated West Coast recording, Way Out West (1957). Hawes would soon be on the way to making jazz history himself. Less than two weeks after putting so much heart and soul, poise and passion, into this recording, the pianist was busted by an undercover cop for heroin possession and sentenced to 10 years in prison. When a relatively hip young president named John Kennedy took over from Eisenhower/Nixon in January of 1961, Hawes saw his chance, put together a case for his release, wrote a letter to Kennedy, and received a presidential pardon three months before November 22, 1963. It’s hard to imagine any single ceremonial tribute — be it an honorary doctorate or a White House medal — ever matching that historic act of executive clemency.

Differences of Opinion

The accepted wisdom at the midpoint in Sonny Rollins’s career was that he performed best in a pianoless setting, He’s admitted as much himself, and when he resurfaced in 1962, the place of a pianist was taken by guitarist Jim Hall. Landmark albums from 1957-58 like Freedom Suite, Way Out West, and A Night at the Village Vanguard would seem to support this idea — at least until you consider the level of his playing with Hawes on this, their only recording together, not to mention what he accomplished with keyboard masters like Thelonious Monk, Tommy Flanagan, Ray Bryant, and Wynton Kelly.

Listening to Contemporary Leaders after live performances ranging from 1980 to 2007 on Road Shows is like going from a rowdy Times Square Saturday night to three-o’clock-in-the-morning intimacy, from a master playing at the top of his bent within a very busy musical element to a group of relaxed musicians going with the flow of the session. That sounds simplistic but in the live performances it’s as if the Colossus has to keep topping himself to conquer an arena packed with willing listeners you know he’s ultimately going to stun, amaze, dazzle, and blow away. In the Contemporary studio, in his 28-year-old prime, he’s no less driving, no less ambitious and unfettered; you can hear him playing hard and smooth, all-out and laid-back, in the same solo. He’s also brashly playful on almost every track, without striving to amuse, which is how it can seem when there’s a crowd expectantly waiting to be captivated. The grunting honking cadenza that ends “How High the Moon” comes off as a bit of fun in the studio rather than the brazen stroke of showmanship it might seem in front of an audience guaranteed to whistle, clap, and cheer all the more because of it.

I have no wish to reopen that other well-traveled argument among Rollins scholars and fans about the confinement of the studio vs. the freedom and challenge of a live performance. The man has discussed the differences often enough himself. In a recent interview for the Catalan magazine Jaç, after observing that “all art has the desire to leave the ordinary,” he’s most likely referring to playing in front of an audience when he says that in jazz “the world of improvisation is perhaps the highest, because we do not have the opportunity to make changes. It’s as if we were painting before the public, and the following morning we cannot go back and correct that blue color or change that red. We have to have the blues and reds very well placed before going out to play. So for me, jazz is probably the most demanding art.”

The newly released live material is definitely more demanding than the music in Sonny Rollins with the Contemporary Leaders, where you have time and space to absorb the discoveries and masterstrokes rather than being bombarded by a titanic display of sheer genius.

I know, being bombarded by genius isn’t exactly a fate worse than death, in case it sounds like I’m trying to scare people away from the many wonders of Road Shows. It’s only that, for me, there’s more deeply satisfying listening pleasure to be found in this apparently underrated studio session, which a Jazz Times review calls “uneven” after admitting that “some people are crazy about this record.” In his otherwise informative study of Rollins, Open Sky (DaCapo), Eric Nisenson actually suggests that “although Contemporary Leaders is an enjoyable enough album, for a perfectionist like Sonny, it was, perhaps, evidence that he needed to go back to the drawing board again.” In fact, his decision to withdraw from the scene in 1959, as Rollins has made clear in numerous interviews, came about because he thought his playing at some live dates around that time wasn’t what it should have been.

As I mentioned, Hampton Hawes is the second master on the Contemporary date. On the runaway soloing that marks “The Song is You,” he not only sustains the pace set by Rollins but seems to be matching him note for note so attuned and resonant is his playing; it’s as if Sonny’s faster than the speed of sound solo with its sampling of “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” never stops but is simply, fluidly translated from tenor to piano. The famous Parker-Gillespie “other half of my heartbeat” metaphor comes to mind when you hear Hawes speaking in the same voice, shading and shaping the “heartbeats” of the notes, keeping pace. Rollins’s tempo creates the sonic equivalent of a brilliant blurring that Hawes picks up on and conveys at the same breakneck speed.

Long known for his knack for making memorable music out of the quirkiest material, Rollins outdoes himself on this album with covers of such unlikely ditties as “I’ve Told Ev’ry Little Star,” “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody,” and “In the Chapel in the Moonlight.” If you think he’s merely amusing himself with pop trifles, just listen to what he does with “Chapel in the Moonlight.” While the other covers (there are no originals in this set) feature his lively sense of humor, they’re no less passionately played. The special late-night all-bets-are-off nature of this session can be felt in the virtuoso ride given “How High the Moon,” which Lester Koenig’s liner notes say Sonny hadn’t planned on recording: “He was jamming the tune with Barney and Leroy at the start of the session, waiting for Hamp and Shelley to arrive. The tape recorders were on, and the result, totally improvised in one take, is a fortunate record of a performance that almost got away.”

Alone Together

You could say the same for the entire October 20-22, 1958 session. What makes it special is the sense of communion, of musicians sharing a time and place and making music that will outlive them. More than any other song on the album, “Alone Together” evokes the late-night atmosphere and the relaxed rapport as each musician pays his respects to the muse. Hawes opens the way with a complexly nuanced statement, at once forthright, easygoing, understated, and then thoughtfully extended by Kessel so that when Rollins comes in the mood has a subtle randomness about it that he explores, dreams on, and then brings home, nailing it, getting it all, the song fading like the musical equivalent of a chance meeting — more an interlude, a snatch of conversation, than a formal statement. The spirit of the song, the way it comes and goes, the sense of its passing, haunts the album and the experience of hearing it, particularly when you think that only one of these musicians is still alive. Hawes died in 1977, Manne in 1984, Vinnegar in 1999, Kessel in 2004 (vibraphonist Victor Feldman, who played on only one track, in 1987) — taking their place among the fallen players Sonny Rollins feels a “holy obligation … to evoke.”