|

|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 31

|

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

|

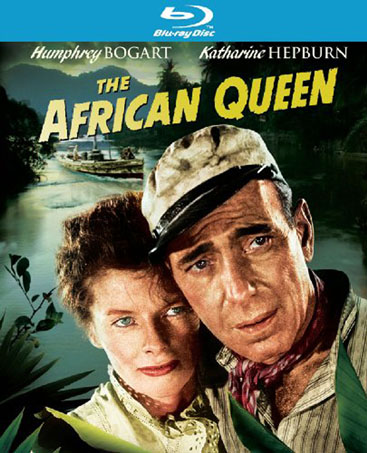

Celebrating “The African Queen” at 60: Bogart, Hepburn, and the Genius of AgeeStuart Mitchner“It is dated, incredible, quite outside acceptable dramatic screen material ... Its two characters are neither appealing nor sympathetic enough to sustain interest for an entire picture ... Both are physically unattractive and their love scenes are distasteful and not a little disgusting. It’s no bargain at any price. No amount of rewriting can possibly salvage this dated yarn.” The judgment above was rendered by a mercifully unnamed script writer at RKO, one of several studios that decided not to take a chance on C.S. Forester’s 1935 novel The African Queen. “A story of two old people going up and down an African river,” British producer Alexander Korda told the film’s eventual producer Sam Spiegel. “Who’s going to be interested in that? You’ll be bankrupt.” The two “old people” being referred to were Charlie Allnutt, the crude Cockney eventually played by Humphrey Bogart (as a crude Canadian) and Rose Sayer, the prim spinster played by Katherine Hepburn. As for the final outcome, the picture was a sensation with both reviewers and the public, grossing $4.3 million in its first run. Premiered in December 1951 so that it would qualify for the 1951 Academy Awards, it received four nominations (Best Actress for Hepburn, Best Director for John Huston, Best Screenplay for James Agee and Huston) while bringing Humphrey Bogart the Best Actor Oscar. The “dated, incredible” screen material was not merely “salvaged” but transformed into one of the most appealing, sympathetic, captivating, tasteful, romantic, uplifting, timeless motion pictures ever made, in or out of Hollywood. The African Queen is among those rare works that make you wish superlatives still meant something. Take the word great. This, one of the most acclaimed and beloved indies (yes, an indie, free of the big studios) ever made, is a great love story, a great adventure, and a great human comedy. Consider, for a start, the odds against an independent technicolor production made in 1951 at the time of the HUAC-driven Hollywood witch hunts and sold by Warners for $50,000 to Sam Spiegel, who had to scuffle to find a backer; then consider the expense and adversity involved in filming on location in Uganda and the Belgian Congo, not to mention the improbability of the romance and of the odd-couple casting of two polar-opposite actors who hardly knew each other and were both politically suspect in the anti-communist paranoia plaguing Hollywood at the time. Besides being a huge personal triumph for Bogart (his first and only Oscar), the picture did wonders for Hepburn. Her performance as the indominitable Rosie leading the Little Boat that Could’s torpedo attack on a German U-boat transformed the moviegoing public’s remote image of brainy, snooty patrician Katherine Hepburn into America’s Kate. As William J. Mann notes in Kate: The Woman Who Was Hepburn (Holt 2006), “With this movie, Kate was transformed into a tower of strength,” having “dispelled any notion that she might be a godless Communist” as the audience “took her to their hearts as their heroine.” Enter James Agee A superlative used less carelessly than great is genius. The African Queen’s genius wasn’t C.S. Forester, who wrote the novel, nor was it John Huston, for all his ingenious directorial contributions; and it wasn’t the brilliant cinematographer Jack Cardiff. The genius whose presence and vision played an indispensable part in this human comedy didn’t accompanythe crew to West Africa. James Agee, who drank and smoked and lived to excess, was in California recovering from a heart attack, the first of a series that would eventually kill him at the age of 45, just three years after The African Queen was released. In addition to the “exceptional intellectual ability, creativity, and originality” of the textbook definition of genius, Agee was possessed of immense emotional intelligence, spiritual heroism, and the total submission to the demons and angels inhabiting Henry James’s “madness of art,” which led to a masterpiece called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941). A more contained form of the same passion went into his writing on film for the Nation and Time and his posthumously published Pulitzer-prize winning novel, A Death in the Family (1957). Two of the subjects of Agee’s best film criticism, John Huston and Charlie Chaplin, would become his friends. He played tennis with both men, spent “30 or 50 evenings talking alone most of the night with Chaplin,” and worked closely with Huston on The African Queen screenplay; awake at all hours writing, he would show up next morning, drained but undaunted, to talk over what he’d written. The importance of his contribution is highlighted in Embracing Chaos, the documentary about the filming included with the Blu-Ray DVD of the film. Agee’s Human Comedy The last part of The African Queen screenplay was written in Africa, by John Huston and Peter Viertel. Otherwise James Agee’s work is the heart of it, and while many of the situations and much of the dialogue is C.S. Forester’s, it was Agee who created most of the film’s unique and memorable moments, notably the sequence highlighted by the eloquent growling of Bogart’s stomach. In a letter from December 1950 to his surrogate father, the Episcopalian priest James Harold Flye, Agee outlined his typically outsized plans for the screenplay, wherein he planned to “blend extraordinary things — poetry, mysticism, realism, romance, tra-gedy, with the comedy.” To build a seminal scene around the social discomfort of a growling stomach may seem absurd, but not if you’re familiar with Agee’s writing on film, where time and again he is able to single out moments of simple, often inadvertent human truth from otherwise unworthy pictures. Agee lavishes an inordinate amount of description on this early scene, the first one shared by Bogart and Hepburn, because it sets the tone of their relationship by juxtaposing a tenuously sustained civility with the odd, natural, funny, and irrepressible behavior of the human stomach, something everyone has experienced at one time or another. Such petty human vulgarities were not permitted in Hollywood, however, at least not outside the realm of slapstick. The censors did, in fact, object to the noises made by Allnutt’s stomach as being “in questionable taste,” which of course is exactly the point of view that is being challenged. It’s no coincidence that Agee’s hero, Charlie Chaplin, liked to subject the Tramp to chronic minor gastric convulsions which “the little fellow” would always politely suppress, hand over mouth, though his body shuddered with the internal impact. Agee’s version of the dyspeptic tramp is the grubby character (Forester called him a “London or Liverpool slum rat”) played by Bogart, who is taking tea with Hepburn’s Rosie and her bald, stuffy Anglican missionary brother (Robert Morley) when “All of a sudden, out of the silence, there is a SOUND like a mandolin string being plucked.” Agee’s all-caps SOUND says it all. This is not a small sound, this is a big sound and not easily ignored. The screenplay has everyone looking away, afraid to make eye contact, Allnutt glancing “down at his middle with a look of embarrassed reproach.” The next one is even worse. Allnutt is about to take another sip of tea “when his insides give out with a growl so long-drawn and terrible that Rose first flinches, then makes a noise across it with her spoon, stirring her tea” while her brother “tightens up like a fist, his first reflex being that this loud one is a calculated piece of effrontery.” After another loaded silence, Allnutt, who “is quite embarrassed, and knows they are,” says, “in a friendly, yet detached tone, ‘Just listen to that stomick of mine.’ “ Still the silence. Allnutt gamely tries to make the most of it, with a remark that also hints at the flavor of his character: “ ‘Way it sounds, you’d think I’d got a hyena inside me.” After a third, less prodigious growling, Allnutt excuses himself and then says, “ ‘Queer thing, ain’t it. Wot I mean, wot d’you spose it is, makes a man’s stomick carry on like that?’ ” The scene as filmed perfectly captures the quality Agee intended, the tension between civility and spontaneity, so nicely and humanly expressed by Allnutt’s last attempt to make the “distasteful” somehow socially redeemable. Among the things Rose will come to love about the little man when she relaxes into being Rosie (and one of the things the audience immediately likes in him) is the sweet, funnily thoughtful way he responds to a minor social crisis. Like Chaplin’s Tramp, he has all the charm of his scruffy humanity, and like the Tramp when he stumbles up against the attitudes and affectations of civilization, he comes off as superior to the situation by being more embarrassed for the other two than he is for himself. The tea scene is of course only the first and necessarily most superficial of the more vividly developed events that form the action romance that audiences over the years have found so endearing and compelling. And since Agee wasn’t present during the filming, the Chaplinesque touch he’s added to the Allnutt character likely had no direct influence on the way Bogart played it. What makes Bogart Bogart is that he’s always had some Allnutt in him, versions of which have surfaced, sometimes in movies he would like to forget, sometimes weirdly and amusingly in his best work, as in the way he tugs at his ear in The Big Sleep, the goofy jokes made about his short stature by the Martha Vickers character, and the bookstore scene in the same movie where Bogart the tough private eye turns himself into a mincing, effete little bibliophile looking for a “true first edition” of Ben Hur. ---- For more about what went on in Africa, read Hepburn’s The Making of The African Queen, Or How I Went to Africa With Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind. The quotes about Chaplin and Agee’s hopes for the screenplay are from Letters of James Agee to Father Flye. As mentioned, Embracing Chaos, a special feature of the Blu-Ray DVD, is worth watching, and so, of course, is the beautiful print. A copy is available at the Princeton Public Library which also has a copy of the DVD. |