|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 31

|

|

Wednesday, August 5, 2009

|

|

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone circling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

The last two sentences of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species quoted above are from the first edition, which came out 150 years ago this November 24 and 50 years after Darwin’s birth, February 12, 1809. The author, who died in 1882, changed the wording in the next edition to “breathed by the Creator.” Both the Everyman Library version and the Norton Critical Edition revert to the original.

Whatever you think about the inclusion or exclusion of “the Creator,” you don’t have to read far in his work before you begin to find the essence of Darwin in surprising places. After reading the Autobiography, and portions of The Voyage of the Beagle, I reread Ernest Hemingway’s “The Big Two-Hearted River,” and felt Darwin’s presence in the deliberate, finely detailed observation of a natural landscape, of, for instance, “trout in deep, fast moving water, slightly distorted … through the glassy convex surface of the pool, its surface pushing and swelling smooth against the resistance of the log-driven piles of the bridge.” Reading D.H. Lawrence, I found the Darwin presence in the poems in Birds, Beasts, and Flowers and all through the amazing passages toward the end of St. Mawr, among them the one about “the circling guard of pine-trees” whose “needles glistened like polished steel” and whose trunks “at evening … would flare up orange-red and the tufts would be dark, alert tufts like a wolf’s tail touching the air.”

Obviously Darwin had nothing to do with what happened when Hemingway depicted the landscape of his Upper Michigan summers, or when Lawrence created his passionate vision of the New Mexican landscape he loved. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that both men are in Darwin country, just as it’s clear when you read Darwin’s Autobiography that he and Hemingway have some other things in common. The author of The Origin of Species admits to having been “passionately fond of shooting” in “the latter part” of his school life and after killing his first snipe: “My excitement was so great that I had much difficulty reloading my gun from the trembling of my hands. This taste long continued and I became a very good shot.”

Revelations

Readers of the unexpurgated version of the Autobiography edited by Darwin’s grand-daughter Nora Barlow will find a writer with a nice sense of style, an open heart, and a full measure of candor, wit, and compassion. Readers looking for his human side will probably be touched by what he writes about his wife and family, not to mention the two remarkable letters from his wife in the appendix and his annotation (“When I am dead, know that many times, I have kissed and cryed over this”). Those looking for some explicit reference to his beliefs will underline the part (once omitted, now restored) where he writes of how “disbelief crept over” him “at a very slow rate but was at last complete,” leading him to admit his inability to see “how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so, the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe … will be everlastingly punished” — after which he declares, in one separate stunning paragraph: “And to me this is a damnable doctrine.”

Then there’s the revelation that Darwin’s nose very nearly changed the course of his life because the captain of the Beagle, the ship of evolutionary destiny, “was an ardent disciple of Lavater, and was convinced that he could judge a man’s character by the outline of his features; and he doubted whether anyone with my nose could possess sufficient energy and determination for the voyage.” Darwin’s timing is right on target as he playfully adds: “But I think that he was afterwards well-satisfied that my nose had spoken falsely.” He picks up the idea again a few pages later when he marvels that “the most important event of my life … depended on … such a trifle as the shape of my nose.” He then seals the theme by recalling the remark made by his father, who had no use for phrenology but who on first seeing him after the voyage, exclaimed, “Why, the shape of his head is quite altered!”

Or consider my personal favorite, which begins with this admission: “But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me.” Darwin isn’t merely expressing his estrangement from the days of his youth when he used to “sit for hours” reading Shakespeare; he’s executing a form of scientific self-analysis on the “atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend.” He goes on to admit that “the loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.” More remarkable still is the explosion of exalted gratification that follows his admission that he has not only become estranged from poetry but has also “almost lost any taste for pictures or music.” What saved the day for Darwin? Novels! Those “works of the imagination, though not of a very high order, have been for years a wonderful relief and pleasure to me, and I often bless all novelists.” And what makes a superior reading experience? “A novel, according to my taste, does not come into the first class unless it contains some person whom one can thoroughly love, and if it be a pretty woman all the better.” Those are my italics, to give some idea of the delight I felt when I read those words. If Darwin doesn’t come alive for you there, he never will. So much for the creationist caricature of the fire-breathing Victorian monster, the ultimate nattering nabob of negativity!

He’s Everywhere

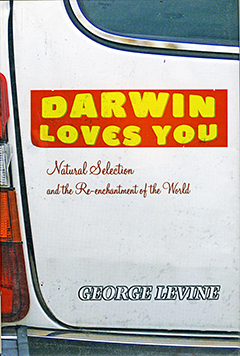

As must be clear by now, what I know about science would barely fit into the pocket of Darwin’s waistcoat. My point of view is that of a sometime novelist, weekly columnist, lapsed poet, and graduate student in English. In addition to the Autobiography; The Voyage of the Beagle; The Origin of the Species; and the Norton Critical Edition edited and selected by Philip Appleman, I’ve been reading George Levine’s Darwin Loves You (his title taken from a bumper sticker playing on “Jesus Loves You”), which was published by Princeton University Press in 2006 and is now available in both paperback and e-Book editions.

Once you begin to appreciate Darwin’s magnitude — the avatar of observation, the naturalist taken to the highest power, or, as Walt Whitman put it, “science incarnate”

— you can begin to see him everywhere, not only in the work of poets and novelists like Hemingway and Lawrence but in every aspect of life. If you imagine the great thinkers, writers, artists of the past two centuries as a mountain range, Mt. Darwin surely casts the longest shadow. The idea he “breathed into” form when Origin of Species was published is still “being evolved” in 2009 in the wonderful, terrible, unthinkably complex world of the internet where the resources and forms are truly “endless,” offering access to the brightest and darkest sides of human nature, from poetry to child pornography, from a benign flow of information to mind-sick propaganda suggestive of George Eliot’s Darwinian epigraph in Middlemarch to the effect that “if we had a keen vision of all that is ordinary in human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow or the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which is the other side of silence.”

Now I find myself having second thoughts about using “Darwinian” in that brutal context. It’s too easy to type the theories his name represents as somehow analogous to the dark side, or more famously, to Tennyson’s “Nature red in tooth and claw.” When I read over the last words of The Origin of Species, citing the “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful” that “have been, and are being, evolved,” I know that my concept of “Darwinian,” based on what I’ve read of him, is in agreement with what Levine is getting at in his subtitle, Natural Selection and the Re-enchantment of the World. Although Levine makes clear that he doesn’t mean to deify Darwin, it’s hard not to attribute something like divine power to the discoverer of a vision of existence, enchanted or otherwise, that encompasses everything from murder and mayhem to peace and love. As the media is already reminding us, it was 30 years ago this week and next (August 9, August 15-17) that the Manson massacre and the Woodstock festival took place.

Close Reading

The more I read in and about Darwin, the more I realize that at its best graduate study in English and the process involved in exploring and “close reading” a vast landscape of literature is itself Darwinian. A more enlightened form of the same thing is also what Levine is doing when he subjects Darwin and his critics to intense scrutiny, training his microscope on specific words that for one reason or another demand special attention. One such word is “nauseated” in the passage where Darwin admits to no longer being able to tolerate Shakespeare. It’s an unusual usage, to say the least. A more conventional term would seem to have been in order and the fact that Darwin suggests being bored to the point of becoming physically ill leads Levine to make some powerful connections in support of his thesis that Darwin’s “rendering of the world, though it is tough-minded and difficult, is derived from and points back toward a humane and loving relation to nature and to people.” A significant element of Levine’s theory involves the “worst moment” of Darwin’s life — ”the death of his beloved daughter Annie,” which Levine connects to Shakespeare and the death of Cordelia in King Lear.

Meanwhile I’m reading Darwin’s simultaneously heartfelt and clinical accounts of ten-year-old Annie’s last days quoted in Darwin Loves You and noticing that the cause of suffering most frequently mentioned was vomiting. If you take the word “nauseated,” connect it to “Shakespeare,” and then note the fact (as Levine points out) that Annie died on Shakespeare’s birthday, April 23, it’s easy to understand Darwin’s visceral distancing of himself from the author who above all others “held the mirror up to nature.”