| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

caption: |

Thomas George and the Adventure of Art

Stuart Mitchner

Speaking about his most recent explorations of the art of the landscape, Thomas George, who has lived in Princeton since 1969, says that the series of "largely abstract images" he's been working on has given him "an assurance that life is worth living as long as there is still adventure." This particular adventure, a retrospective of the 86-year-old artist's work, opened Saturday at the Princeton University Art Museum and will be on view through September 11.

Placing Princeton

During a sneak preview of the exhibit last Thursday, I saw the 25 works before they had been tagged with titles and dates. The first image that catches your eye as you enter the room is a brilliant autumnal pastel so rich with the presence of Princeton you don't need a title card to tell you where it's coming from. Returning to it after the show opened, I discovered that the subject of that burst of color was the pond at the Institute for Advanced Study, where the artist had been at nine a.m. on October 11, 1993. The recording of a specific time suggested that this was one of many visits to that spot. In fact, another pastel devoted to the same subject informs us that he came back there again at seven a.m. on May 9, 1995 when he produced a cooler, softer version of the pond in another season. Once I knew the specifics of time and place, it was no longer so easy to look at those images objectively. Anyone who has enjoyed that particular Princeton scene will recall their own experience of it, probably along with some unique impression, like the memory of an exotic dog someone was walking, or the time your 5-year-old son fell in the pond. It's hard not to compare your personal sense of the scene with the artist's, and it gives the work a special resonance to imagine the painter venturing out day after day to explore and transform a place you may have taken for granted.

For people who know Princeton, the pen and ink drawing of a Norwegian Spruce in Marquand Park is more instantly recognizable than either of George's depictions of the Institute pond. Even so, it's tempting to look deeper into the surface image and imagine the complex natural tree form being used to suggest the shadows, cross-purposes, conflicts, complex struggles, triumphs and tragedies of a human life; it reminded me of the way the conflicting, converging, overarching jets of water in the Woodrow Wilson School fountain suggest the triumphs and tragedies of Wilson's career. This sort of cross-referencing, chain-reaction dynamic of associations created by a single work is the essence of the art adventure.

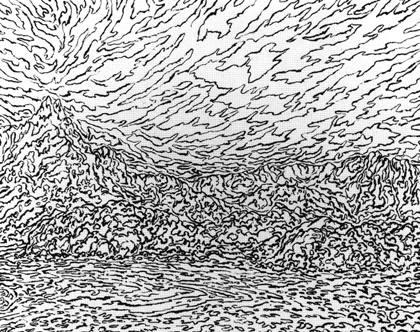

When I was looking at the black-and-white scenes from Norway, China, and Japan at the center of the exhibit without knowing the titles, the viewing experience began to feel uncomfortably close to a glorified Rorshach test. The Chinese landscapes suggest Chinese scroll art, much as the Temple Garden, Kyoto, suggests a Japanese print. All these visions are rendered with compelling force, but one in particular shows the artist stirring the elements of a landscape into action. Lofoten was drawn in brush and black ink in Norway's Lofoten Islands, "one of my favorite places," the artist says in an interview with Richard Trenner featured in the brochure: "a wild landscape in which the turbulent movement of the sea and sky seemed to make the mountains move as well." The action here is so loose and fluid, yet intricate, that it seems on the verge of becoming intelligible, something the artist himself suggests when he speaks of inventing "a calligraphic language" for the picture. In this context, it's interesting to note that George drew terrain maps used in coastal invasions when he was serving in the U.S. Navy in World War II. Here, the land mass looks complex and congested as the forms seem to expand into flight, almost as if the land was a maze the artist navigated on his way into the sky.

Asked in the interview about the roles of black and white and color in his work, George spoke of using gardens in France and England as "color laboratories" where he learned to "think and speak more fluently and expressively in color." The three garden scenes on display side by side are Monet's Garden, Giverny (a darker vision than one might expect), done in 1983, and two pastels from Wales in the early 1990s. The one simply titled Bodnant Garden, Wales, with its muted Turneresque sunburst, is one of the most striking pieces in the exhibit.

Finally, to show us the source of his continuing sense of adventure in art, one of the latest works, done in 2004, is on display. Executed in brush and black ink and gray wash, the landscape is unidentified. In this instance, the white mass of hill or mountain looks at once austere and mysterious in contrast to the agitated black forms erupting onto it. If these later works are, in his words, "distillations" of what he has learned about the natural world, this particular landscape seems less a refinement than an intensification. Like much of Thomas George's best work, it does not wait for you to come find it or critique it; it comes right at you.

A World Class Museum

Such is the scope and depth of this museum, this Princeton treasure, if you have time, you can walk into another room on the same floor and see Giverny as Monet himself painted it a hundred years before. Or you can compare George's landscapes with Cézanne's Mont Sainte-Victoire. Or you can compare them with unique and unlikely landscapes by Klee and Kandinsky. Or, after admiring the deep green and black contrast in George's Sky and Green Earth, you can discover a similar blend in Emil Nolde's Twilight. And this extraordinary adventure in art can be experienced in a relatively compact, navigable venue a few minutes walk from the heart of Princeton.

Speaking of the museum in general, it was good to see that Red Groom's Cedar Bar tableau of the 1950s art life in New York has been moved from relative obscurity at the far end of the main floor to a prominent position in the front room. Now instead of looking down into the bar where Pollock and DeKooning are holding forth, you look directly into it, head on. It's almost as if you could walk inside and be part of the crowd.

You have all summer to take advantage of this world-class museum, which is open to the public without charge Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m to 5 p.m and on Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m. It is closed Monday and major holidays. Tours of collection highlights are given every Saturday and Sunday at 2 p.m. The museum is located in the center of the Princeton University campus, next to Prospect House and Gardens. For further information, call (609) 258-3788 or visit www.princetonartmuseum.org.