|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 15, 2007

|

|

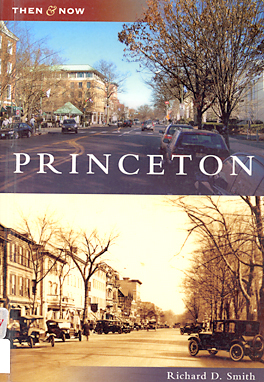

Dedicated to the memory of Gail Stern, who died in 2006 after spearheading the Historical Society of Princeton (HSP) for 13 years, the new edition of Richard D. Smith’s Princeton in the Then and Now series (Arcadia $19.99) offers an irresistible tour of the town Albert Einstein once compared to “a well-smoked pipe.” Like other Princeton residents, famous and otherwise, Einstein haunts this little book, and as the terms of his analogy suggest, he eventually felt very much at home here (early on, this was not the case); in fact, the well-loved armchair in which he enjoyed that well-smoked pipe was donated to the HSP and Bainbridge House during Ms. Stern’s tenure.

The images of Princeton’s past Mr. Smith has drawn from the HSP collection are bound to set off a chain-reaction of memories and associations, particularly in people who have lived in Princeton long enough to appreciate what has changed, what is no longer here, and what is no longer where it used to be.

The Trolley Song

Let’s start with the picture of the trolley car on page 28, which looks somehow out of place on Witherspoon Street even in the 1930s. If I have a weakness for this particular vehicle it’s partly because it resembles the most storied trolley in all cinema — the one taking a seriously estranged husband and wife (he almost murdered her) into the big city that reunites them in F.W. Murnau’s great film, Sunrise. The ringing of trolley bells that was once a part of daily life on Witherspoon Street (“Clang, clang, clang went the trolley/Ding, ding, ding went the bells/zing, zing, zing went my heartstrings”) must also have quickened the pulse rate of a Princeton freshman named Eugene O’Neill who arrived in fall 1906 and was expelled in spring 1907. The future Nobel-prize-winning playwright used to take The Princeton Fast Line trolley to Trenton for the bouts of debauchery that figured in his expulsion. Quoted in Arthur Gelb’s biography, O’Neill says he “flunked out...for over-cutting.” While his trolley rides to Trenton to see the Anna Christies of the red light district clearly conflicted with his study-time, the last straw may have come the night he missed the 11:18 p.m. trolley back and had to take a 1 a.m. train to Princeton Junction, whereupon he threw a stone through the stationmaster’s window to silence (it is said) a barking dog. The stationmaster’s complaint led to a two-week suspension.

My own chain-reaction of memory impressions set off by this same photo involves regular father-son outings on what we called the Trolley Walk because the bike path we followed was the same right of way used by the Princeton Fast Line speeding Eugene O’Neill on his way to sin and glory. You can walk the route by parking in the Elm Court lot and heading down the path toward Johnson Park School. Hiking through the unpaved portion of the trail had a special scary fascination for an overprotective father and a six-year-old because when we pushed through the often thorny overgrowth and came out above Stony Brook, the ground gave way to empty space with startling abruptness. The trestle was long gone but the three pylons were still there supporting a phantom span. That sudden cessation of solid ground caused the father a few anxious moments since his stubborn, daredevil son was usually charging ahead and had a tendency to make sudden grabs at flowers or occasional frogs and snakes, unmindful of the abyss that lay ahead.

Lost Moviehouses

The photo of the Princeton Playhouse on page 94 can be placed in time because the movie featured on the marquee, I Live On Danger, came out in 1942. The caption says that Einstein “enjoyed Saturday matinees there,” and it’s easy to imagine Princeton literati like John Berryman, Saul Bellow, and R.P. Blackmur going in some years later and coming out talking, or, more likely, arguing. You can bet John McPhee saw his share of movies at the Playhouse when he was growing up (he’d have been around 11 when I Live On Danger was playing); he cared enough about the place to salvage some fieldstone remnants of the building after its demolition. Reading the description in the WPA Guide to New Jersey should shame whoever’s responsible for the theatre’s demise: “The walls of the foyer are finished in metal; the shell-shaped and serrated ceiling of the auditorium, based upon Dr. H. Lester Cooke’s isophonic curve theory of the perfect reflection of sound, is called the first of its kind in the world.” Now you know one reason Einstein and no doubt some of his colleagues from the Institute were drawn to the place. At least it was replaced by a restaurant, Mediterra, that has kept the Princeton Playhouse spirit alive by sponsoring Monday night Movies in the Plaza during the summer months.

In remarks at a Princeton Public Library event in his honor last year, Mr. McPhee mentioned a boyhood fondness for another vanished moviehouse, the Arcade, which was located where the Triumph Brewery now stands. On the subject of Princeton and change, he quoted from one of his own books: “Stay here all your life and you get a new town every five years.”

Speaking of movies, look at the picture of the frame structure that used to sit on the site of the Tudor Revival building (formerly Pyne Hall) now housing Hamilton Jewelers (p. 17). It’s not wholly fanciful to imagine that the African American youngster sitting on the curb could be Donald Lambert, who would grow up to become one of the great stride piano players and who was good enough at age 10 to accompany silent movies, most likely the ones screened at the Princeton Theatre at Spring and Witherspoon. That’s the same corner shown in the photo of the Princeton-Trenton trolley, by the way. And if you ever want to hear why Donald Lambert’s virtuosity was legendary, listen to his breathtaking, breakneck version of “The Trolley Song.”

Micawber to Labyrinth

You may be reminded of Princeton’s most recent loss when you see the Bickford Building (p. 30), constructed in 1913 (once the home of an A&P ), and its successor (built in 1950), which was home to Woolworth’s and adjoined the late lamented bookshop named for Mr. Micawber. But here comes “another new town” — something’s always turning up — in the form of another business planned for the ghostly footprint of A&P and Woolworth’s this fall, a state-of-the-art bookstore called Labyrinth.

Sailing On

If there are no pictures of Lake Carnegie, perhaps that’s because it’s harder to find one of a body of water that suggests an older time. You’d need to put a man in a straw hat and suspenders on the shore with a girl in a hoop skirt. Or better yet, find a picture of Albert Einstein out there drifting into history on the still waters of the lake in his little second-hand sailboat.