|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 33

|

|

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

|

|

People who listen to the Beatles love them — what about that?Richard Poirier, “Learning from the Beatles”

In case you doubt that loving the Beatles can change your life, here’s a long and winding road of a story that begins in a school gym in Trieste where an American hitchhiker is standing in front of two big amps getting his first taste of amplified rock and roll up close in person. He is amazed. The Beatlesque group onstage call themselves the Five Fans and the Yank is there because Oscar, the keyboard player, gave him a lift about ten miles out of Venice. The two rosy-cheeked lads sharing the mike are singing “She Loves You” face to face and shaking their Beatle haircuts just like Paul and John in A Hard Day’s Night, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Hitching out of Trieste next morning the American gets a lift from a small, rotund Iranian in a new VW he’s still learning how to drive; he’s going all the way to Tehran and seems to think he can make it on one tank of gas because he’s got a 45-rpm record player attachment under the dashboard and only one record to play on it, “Help” by the Beatles, which he prompts the American to keep putting in for him because his arm isn’t long enough even in a VW and he doesn’t intend to stop again until he gets to Tehran, about 2000 kilometers to the east. Every time the song finishes, the Iranian says, “Playplay,” and after about the twentieth time it dawns on the hitchhiker that the driver thinks that by keeping a record called “Help” constantly playing, he’s somehow adding fuel, as if there’s some kind of magic Beatles octane flowing, and it’s a tribute to the staying power of the song that after surviving that mad ride the hapless hitchhiker loves “Help” as much as he ever did — more, in fact. A few days later he’s in Istanbul loving A Hard Day’s Night for the ninth time. A few weeks later he’s in a Calcutta record shop listening booth with some friends loving the Beatles for Sale album and wondering how can it get any better than this. Six months later he’s with a girl he loves finding out how much better it can get as they bliss out together to the entire Revolver album in a record shop listening booth in Salzburg. A few years later the hitchhiker and the girl are married and he’s doing graduate study in English at Rutgers because an essay about the Beatles by Richard Poirier, the chairman of the department, changed the course of his life.

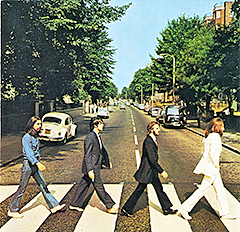

The Zebra Crossing

It was a hot day in London, a really nice hot day …. I didn’t feel like wearing shoes. So I went around to the photo session and showed me bare feet.Paul McCartney

Forty years ago on the morning of August 8, four men, one of them barefoot, are striding in single file across the zebra crossing in front of EMI’s Abbey Road recording studios while a photographer named Iain Macmillan takes pictures and a London bobby holds traffic at bay. The historic cover shot — you could call it the shot seen round the world — takes about 10 minutes as John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr cross and recross that now-hallowed pedestrian walkway. While the montage of some 60 celebrities, living and dead, featured on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band probably made a deeper impression on the consciousness of the culture, it was a fantasy. Not so the cover of Abbey Road. The site in the picture is real; it’s still there; it can be visited, and so it is, day after day, year after year, by real people of all ages from all around the real world, there to walk in the footsteps of the Beatles and take pictures of themselves doing it. If you prefer the comfort and economy of a virtual visit, you can access the Abbey Road crossing, day or night, 24/7, courtesy of EMI’s webcam (www.abbeyroad.co.uk/visit).

Another Anniversary

The last time all four of the Beatles were in EMI’s Studio Two working on the same project (overseeing the ultimate mix and “running order” for Abbey Road), it was 40 years ago and a day, August 20, 1969, which was also when the album was essentially completed. Though the record was released half a year ahead of the long-delayed, battle-scarred Let It Be, Side Two of Abbey Road stands as the group’s true swan song. Outspoken as always, John Lennon dismissed the sublime denouement as “just junk … just bits of songs thrown together.” He was no less hard on his own contributions to the farewell medley, disparaging “Because” as “a terrible arrangement, a bit like Beethoven’s Fifth played backwards” and “Sun King” as “a piece of garbage I had around.” As McCartney admitted in a 1984 Playboy interview, John wasn’t one to “dish out” praise: “If ever you got a speck of it, a crumb of it, you were quite grateful.” Of course Lennon’s tough love attitude had a lot to do with why the Beatles were always outdoing themselves.

Sides? What Sides?

People who came of age in the post-LP era might be wondering “What’s all this talk about sides?” In days of old, the object you pulled out of the record sleeve had two sides, and if one happened to hold you more than the other, that’s the one you kept putting on the turntable until, as happened here, it became its own self-contained album. Look at the track listing on the back of the Abbey Road CD, and you find nothing to indicate a dividing line between the long, stormy, demonically symphonic coda to John Lennon’s “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” that ends Side One and Side Two’s opening song, “Here Comes the Sun,” one of George Harrison’s most inspired contributions to the Beatles repertoire. Side One is a collection of more or less unrelated songs, which was usually the case before the Beatles and others began making “concept albums.” Along with Harrison’s ageless ballad “Something,” which he thought “probably the nicest song” he’d ever written, you’ve got “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” and Ringo’s “Octopus’s Garden,” two cute, impeccably produced numbers that sound a bit thin once you’ve been exposed to the splendors of Side Two. Even the virtuoso singing on McCartney’s “Oh! Darling” sounds like overkill compared to Harrison’s gently sung “Little darling,” the first words of “Here Comes the Sun.” As for Side One’s opening track, “Come Together,” which Lennon says began as a “campaign song” for Timothy Leary when Leary was considering running against Ronald Reagan for Governor of California, its origin alone suggests why, with its mixture of self-mockery, politics, and “Ono cycle” word play, it would be more at home on a John Lennon solo album. It isn’t until the “garbage” on the second side that you get the heartfelt essence of the man. Another key to the dynamic that drives the Beatles is the mixture of love and anger projected by Lennon, the cynic, the wit, the putdown artist, who has a voice and a gift for feeling that can make “Sun King” — that “piece of garbage” — into a thing of beauty.

Even so, Paul McCartney and producer George Martin deserve much of the credit for the glory of Side Two. So brilliantly paced and arranged is the medley woven together with those “bits of songs” John disdained that you’re too swept up in the music to question anything, including McCartney’s somewhat preachy declaration that “the love you make is equal to the love you take” at the end of “Carry the Weight.” Lennon actually dished out some faint praise for what he called a “cosmic, philosophical line” that “proves that if [Paul] wants to he can think.” The truth is, Paul didn’t need to be so explicit. It’s understood, as Richard Poirier observed: “People who listen to the Beatles love them.” In other words, it’s the music they make that equals the love people take from it, and a lot of people carried the soul-sustaining weight of Abbey Road’s magic medley close to their hearts in the decades that followed the summer of ’69.

A Hard Day’s 1964

Now think back 45 years to the summer of ’64. Not only did the Beatles achieve their conquest of America that year, they came through with A Hard Day’s Night (the album and the film) and later the same year Beatles For Sale. A recent story in the New York Times suggests that their music is bringing people together (“Generation Gap Narrows, and the Beatles are a Bridge”), as if that were something new. In fact, A Hard Day’s Night was bridging generations and seducing audiences of all ages, races, creeds, and colors back in 1964. A year later, in London, I found myself walking among excited, exhilarated crowds near Piccadilly Circus. Something special was at hand. It was like a reversal of Blake’s “London.” Instead of bearing “marks of weakness, marks of woe,” these faces were smiling because the Beatles were just around the corner attending the premiere of their second film, Help. What could one do but smile? The joy-givers were near and love and music were in the air.

Richard Poirier’s “Learning from the Beatles,” which appeared in Partisan Review in 1967, can be found in his landmark work, The Performing Self (1971). The founder of Raritan, co-founder of the Library of America, and longtime professor of English at Rutgers, Richard Poirier died this past Saturday at the age of 83. Making special mention of his writing on the Beatles, The New York Times obituary credits him for recognizing “the emergent interaction between ‘serious’ and pop culture” and “the revolution that the Beatles … had begun to effect in American cultural life.” The obituary by Bruce Weber also points out that “Poirier” rhymes with “warrior,” a nice connection given the courage and conviction of his work.

My other sources were William J. Dowlding’s Beatlesongs and Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles Recording Sessions.