|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 35

|

|

Wednesday, August 29, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 35

|

|

Wednesday, August 29, 2007

|

|

Mush!” we yelled whenever a movie cowboy romanced, or worse, sang to, a comely female. No dictionary I’ve consulted online has traced the genesis of that particular use of the word back to action-hungry kids at Saturday matinees. Film critics in embryo, we shouted it loud and clear, in between boos and whistles. We came to see the hero gun down the bad guys and here he was wasting his time mooning over some silly schoolmarm. Maybe we had a point. When you think of all the travesties of love that have been put on film over the years, all the bogus sentiment, the soft-focus close-ups and tender words, all the soap-opera-level moves, all the corny clichés and stereotypes of paint-by-the-numbers romance, not to mention marathon kisses and simulated sex, it’s enough to make you take a cue from James Agee and join the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Love.

Movies handle the sacred subject best when they don’t come at it head-on. Better to keep romance light and amusing, or else set off by unexpected events and unlikely relationships, like two cowboys falling in love, or a woman and an ape. I haven’t seen all of Hollywood’s latest version of King Kong but every time I surf HBO it seems Naomi Watts is there swooning in the palm of Kong’s hand. Fay Wray just screamed a lot. Naomi Watts actually creates a love scene with the big guy simply by looking adorably desirable and refusing to camp it up. Not since the days of the Gaze (remember Nancy Reagan’s worshipful contemplations of the president?) have a woman’s mutely adoring looks done so much to express the cause of true love.

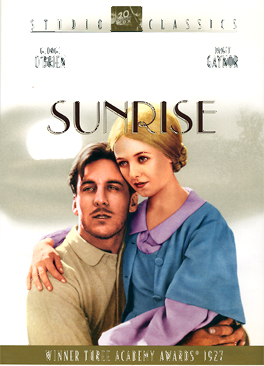

The Virtue of Silence

The awful truth is that the course of movie love seems to run smoothest when the lovers have no voices, as is the case in two of the best movies ever made, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise and Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, both of which opened in American movie theaters eighty years ago. With rare exceptions, that’s how far back you have to go to find a movie where the men are allowed to feel and yield and love as fully as the women. Had either film been made a few years later when sound was the norm, a good deal of emotional magic would have been lost, or, at least diminished. One thing these pictures have in common besides having been made at the same studio (Fox) with the resources of the same art department is that both do full justice to love. Even more important is the presence of Janet Gaynor, who won the first Best Actress Oscar for her performance in both films (and in another Borzage romance, Street Angel). It’s doubtful that any other actress, let alone a virtually unknown 22-year-old, ever had the experience of being the shining center of two masterpieces made in the same year by two major directors. In an interview years later, she said, “To go from Murnau and Sunrise to Borzage was enough contrast for a lifetime. Murnau was all mental, Borzage totally romantic--all heart.”

Laughing at Beauty

Needless to say, silent movies, especially silent romances, are an acquired taste. Screen Sunrise or 7th Heaven to a contemporary audience, and there’s a chance you’d soon hear patronizing laughter — so archaic, so quaintly amusing, these creaky old things.

When Sunrise was shown to a relatively enlightened group on the Princeton campus some years ago, people laughed to see little Janet Gaynor running just a bit too speedily away from her hulking husband; you’d have thought it was a chase scene in a Roadrunner cartoon rather than the flight of a wife who had just seen her husband come within a heartbeat of murdering her. At a long-ago showing of 7th Heaven in New York, the revival house audience laughed when the petite Gaynor (as Diane) was lifted up and hugged by the towering Charles Farrell (as Chico). But no one was laughing after the first lingering close-up of the radiant natural beauty of Gaynor’s Parisian waif at the moment she knows she is loved by the man she loves. One of the keys to a convincing depiction of romance onscreen is that the audience fall in love with the lovers, most especially the female. Audiences fell in love with Janet Gaynor, and she and Farrell became “America’s Sweethearts.” 7th Heaven was a box office sensation. Not so Sunrise.

Love and Death

While Sunrise bombed at the box office, it’s a much more celebrated film, usually turning up whenever film critics and scholars are polled about the “greatest films of all time.” 7th Heaven is beautifully directed and shot, but most of the imagery is devoted to developing and celebrating the relationship between the lovers. Sunrise is a feast of cinematic virtuosity. Even the titles are done with visual flair. When the woman from the city (Margaret Livingston) seduces the farmer (George O’Brien) and suggests that he get rid of his wife (Janet Gaynor), the letters of the title “Couldn’t she get drowned?” drip down and dissolve like water. As the temptress makes love to her hapless, all but catatonic victim in a moonlit field, trying to lure him away from his farm and his marriage (and baby) with visions of big city excitement, the letters of the title “Come to the City” loom with a hypnotic immensity as the sky above the field the two are lying in (the vamp coiled around her victim like a snake) is filled with a delirium of city visions, bright lights in a magical swarm, tall buildings, electric signs, bands playing, people dancing.

What you remember from seeing 7th Heaven are the exalted faces of the lovers and, especially, Diane in her ruffled wedding dress standing in the window of the garret like a vision. What has contributed most to Sunrise’s reputation is the bravura direction and the extraordinary photography of Charles Rosher and Karl Struss: the Vermeer-like clarity of the table set by the wife (herself a perfect Vermeer portrait) for the dinner the husband is lured away from by the vamp; that misty moonlit field he lumbers heavily across (Murnau actually weighted his boots with lead) on his way to meet her, moving like a sex-enchanted sleepwalker; the almost-murder scene on the lake where the husband looms over his terrified wife, his ape-like movement so extreme it might well provoke laughter in a contemporary audience; the tram ride into the city; the city itself, a fantastic improvisation on the idea of a metropolis that at first intimidates and then helps reunite the couple. Finally there are the wild carnival scenes that begin with a fantastic exploding pinwheel and are followed by a deadly storm that descends on the couple as they row homeward on the lake.

The heart of the movie, however, has little to do with filmic showmanship. Without it, Sunrise could not be mentioned in the same breath with a love story as rich as 7th Heaven. In Borzage’s film, the lovers are challenged by the man’s pride, the woman’s beaten-down fear of life, the First World War, and death itself (Chico literally comes back from the dead). No less powerful in Sunrise is the way in which the moment on the lake, when the wife raises her hands in prayer as her husband hovers murderously over her, leads to a rebirth of love in the city that fully justifies the film’s subtitle, A Song of Two Humans. The song, as such, begins with the tram ride to the city, probably the most famous sequence in the film. Think of the situation: the wife in shock, the husband desperate and passionately remorseful, his repeated plea, “Don’t be afraid of me!” the only words spoken in the course of the ride, the tram moving with unreal smoothness, gliding dream-like around turns, the view through the windows changing from lakeside and country to city outskirts and as signs and buildings and traffic multiply.

The woman runs from him again as soon as they reach the terminus at the city’s center. After catching up in time to stop her from running blindly into a maze of frantic traffic, he guides her into a restaurant and brings food to the table, but when she tries to eat, she begins to weep. They’re still in the shadow of the moment on the lake, both dazed, bemused, haunted by what almost happened. While they’re in the restaurant, the flow of people and traffic outside the window never stops. A rugged man more at home in westerns than romances, O’Brien carries these scenes, his demeanor at once abject, penitent, loving, and thankfully mute. Spoken words would have violated the simplicity of his gestures. After gently, miserably shepherding his still shaken wife from place to place, he leads them into a church during a marriage service. At first, neither one seems to understand the significance of the setting, but when the minister recites the marriage vow “to keep and protect her from all harm,” the husband breaks down and buries his head in his arms as the impact of those words overcomes him. Again, the scene takes force from the fact that nothing is said, that we can’t hear him sobbing and can’t hear her consoling him as she rests her head on his. They walk out of the church ahead of the actual newlyweds, their marriage renewed.

From then on the city is their plaything. Even more, it’s Murnau’s. He came over from Germany to direct the picture with the contractual understanding that there would be no interference, and Fox kept its word. Given a free hand, he made the most of it, and in the scenes that follow the hushed reunion, he seems to be intoxicated by his own hilarious vision of the carnival of life, and the two actors are as if carried along by the director’s creative frenzy. The Song of Two Humans becomes gay, raucous, drunken. A pig runs wild, gets drunk on spilled wine, and is finally heroically corraled by the husband. Then the couple are encouraged to do a peasant dance. The city loves them and they love the city, and the husband is enjoying a version of it even more animated than the one created in the sky above the field when the city woman was telling him of its excitements.

The DVD of Sunrise is not easy to come by, but the film shows up fairly often on the Fox Movie Channel, where it can be seen September 14 at 6 a.m., October 12 at 8 a.m. Like most of Frank Borzage’s work, 7th Heaven is not available in this country on either video or DVD. Why Fox hasn’t seen fit to release this classic is puzzling and a bit ironic, since it was the more popular of the two. Sunrise was such a box office disaster that it marred the remainder of Murnau’s brief career at Fox. Never again was he given a free hand.