|

|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 35

|

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

|

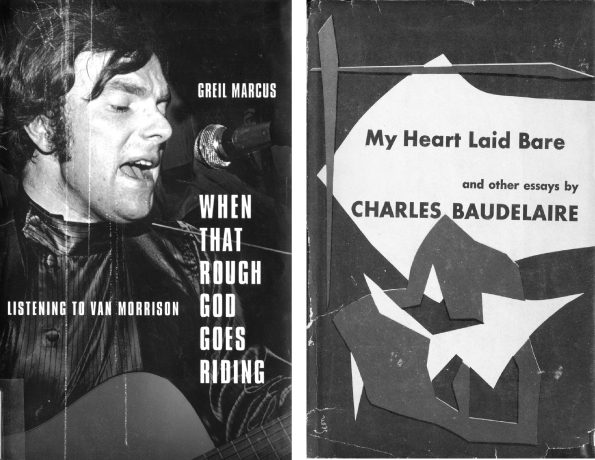

Tuning In Radio Free Baudelaire on Van Morrison’s BirthdayStuart MitchnerBe Drunken, Always. That is the point; nothing else matters... Drunken with what? With wine, with poetry or with virtue, as you please. But be drunken. And if sometimes...you should awaken and find the drunkenness half or entirely gone, ask of the wind, of the wave, of the star, of the bird, of the clock, of all that flies, of all that speaks, ask what hour it is; and wind, wave, star, bird, or clock will answer you: “It is the hour to be drunken!” — Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) Fly it, sigh it, try it.... Fly it, sigh it, c’mon, die it.... — Van Morrison, from “Ballerina” For all I know there’s a foot of water in the finished basement room where the effluvia of Irene is streaming in because the outside pumps aren’t working even though I tested all three of them, and worse, the back-up sump pump is flashing its red alarm light, meaning that when the power goes off, as now seems inevitable, we’ve had it. At 2 a.m., with the water pouring in on both sides of the basement, it’s like Baudelaire says, “the hour to be drunken.” Wind and wave are telling me there’s nothing for it but to trudge upstairs and listen to Astral Weeks, one of the most intoxicating albums ever made, of which people say, as reported by Greil Marcus in When That Rough God Goes Riding: Listening to Van Morrison (Public Affairs 2010), “‘I’m going to my grave with this record, I will never forget it.’” August 31 is not an insignificant date for either Morrison or Baudelaire. The composer of Astral Weeks is born on that day in 1945; the author of Flowers of Evil dies on that day in 1867. A hundred years later on March 29, 1967, Morrison records “TB Sheets” at A&R studios in New York. Knowingly or not, he’s picking up a strong signal from RFB, Radio Free Baudelaire, and his reception is even better in the fall of 1968 when he, along with bassist Richard Davis and all the right people land in the right place at the right time and create Astral Weeks. Trapped “T.B. Sheets” is a wrenching, relentless sick-room complaint that pants and heaves for almost ten minutes between the walls of its own claustrophobia. Like Baudelaire’s “The Double Room,” where a knock on the door turns a “paradisiacal” space into an “abode of eternal Ennui” (“one breathes here only the rancidity of desolation”), the room in “T.B. Sheets” inflicts pain, the light “through the crack in the window pane” numbing the brain of the entrapped singer telling his consumptive Julie “It ain’t natural for you to cry in the midnight” as he backs off from the terror in the room: “I see the way they jump at me Lord, from behind the door, and look into my eyes.” Unable to breathe, he opens the window (in Baudelaire’s room the windows are “sad and dusty”), looking down at the street below before he lets it out, wailing, “And I can almost smell your T.B. sheets, on your sick bed.” He wants to go, she wants him to stay, and it’s he, not she, who needs a drink of water. You can hear his footsteps as he goes off to get it. He finally escapes after promising to send somebody around later “with a bottle of wine for you, babe.” Leaving isn’t easy. He starts and stops, “Gotta go, gotta go, gotta go, gotta go.” Before he leaves, he turns on the radio, in case “you wanna hear a few tunes.” If that’s Van Morrison’s personal radio on the bedside table, Julie will have a whole world to listen to. Turn It Up! Turn up your radio and let me hear your song.... Turn it up, turn it up, little bit higher, radio Turn it up, that’s enough, so you know it’s got soul.... — from “Caravan” In Van Morrison’s version of Genesis, you could say, “In the beginning, He turned on the Radio.” His most visible and renowned performance of “Caravan,” from the 1969 album Moondance, was recorded by Martin Scorsese in The Last Waltz. As described by Greil Marcus, the star-studded farewell concert for The Band had “nearly come to a halt” when Van the Man “turned the night around,” and “as the horn section pushed back, louder each time...matching it in volume, he began to kick his right leg into he air like a Rockette. He shot an arm up, a dynamo, the movements repeated, repeated, repeated, and shocking every time.” In Marcus’s words, “he had taken everything the song had to give, he had left nothing out...It was always a song that demanded to be made a testimony — this is the last song I’m ever going to sing in my life — and that’s what Morrison gave back.” Radio Nights Radio Free Baudelaire was on Van Morrison’s wavelength as early as “Mystic Eyes,” which he recorded in 1965 with his group Them. According to Morrison, who pulled that searing, hellbent song out of the air in the flux of a recording session, the words were inspired by the sight of children playing in a graveyard and the thought of “the bright lights in the children’s eyes...and the cloudy lights in the eyes of the dead.” Recorded when he was 20, “Mystic Eyes” may have been the first and most explosive piece cut from the heart of Morrison’s Belfast nostalgia. As he eased into his forties, some of his most affecting songs harked back to Belfast nights listening to rhythm and blues and jazz on the Armed Forces Network and Radio Luxembourg. “Elvis did not come in/without those wireless knobs...Nor Sonny, nor Lightning, Nor Muddy, nor John Lee.” The allusions range from Jelly Roll Morton to Debussy, from Wilson Pickett to Piaf. Morrison’s lyrics from the same period also salute his literary heroes, forming a landscape of poets and writers in the evocation of specific locales, Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lake Country, Blake’s Albion, Yeats’s “uninhabited, ruinous” house from “Crazy Jane in God.” Although there’s a song for Rimbaud (“Tore down a la Rimbaud”), Baudelaire is nowhere to be found, at least not on the surface. Even so, his presence in Morrison’s music of the late sixties is as pervasive as it is unstated. The other poets are mostly celebrated in passing, like companion spirits. The spectral presence of Fleurs du mal and Spleen de Paris that haunts the sick room in “TB Sheets” hovers over the slipstreams and backstreets of Astral Weeks. The “viaducts of your dream” in the title track could be an image out of Baudelaire’s “death-fraught idyll” of Paris. The bold beauty of the “little girls on the way back home from school” conquers the man in the car in “Cyprus Avenue” (“I may go crazy before that mansion on the hill”), while the room in “Madame George” with its smell of sweet perfume “drifting through the cool night air like Shalimar” could be in the hashish-eater’s Hotel Pimodan on the Ile Saint-Louis. A Baudelaire angel is “Ballerina,” from the first lines (“Spread your wings. Come on fly awhile straight to my arms little angel child”) to the breathless, intoxicated flow of “Fly it, sigh it, try it” like the flow “of the star, of the bird, of the clock, of all that flies, of all that speaks” in “Be Drunken.” The last song on Astral Weeks, “Slim Slow Spider,” harks back to “T.B. Sheets” (“I know you’re dying, baby/And I know you know it, too”). Greil Marcus calls the sudden violent conclusion of this once-in-a-lifetime album “a farewell, in the form of a closing door” that bassist Richard Davis “rattles...in its frame.” Heaped Listening to Astral Weeks on a CD Walkman with a lantern nearby while Irene roars and blusters in the background, I know that even if the power goes out, the music will keep playing. I’ve got a seven-pack of AA batteries but I don’t need them. The power stays on, and downstairs the water is slim slow sliding away, the floor is already getting dry, and I’m wishing I could call someone who will know what I’m talking about when I tell them that the music I just listened to has, as Captain Ahab would have it, heaped a hurricane. “What does it say, where did it come from?” Marcus asks as he ponders the “inexplicable” greatness of Astral Weeks. His answer, as good as any, is that this music tells both musicians and people who aren’t musicians “there’s more to life than you thought. Life can be lived more deeply–with a greater sense of fear and horror and desire than you ever imagined.” Writing in the book he’d been “dreaming of for years,” Baudelaire says, “I cultivated my hysteria with delight and terror.” The book was to be titled My Heart Laid Bare (Mon coeur mis à nu). “Be Drunken” (“Eniverez-Vous”) is from the Arthur Symons translation of Baudelaire’s Paris Spleen (Petits Poèmes en prose). The DVD of The Last Waltz is at the Princeton Public Library, as is Greil Marcus’s book, which does full justice to Van Morrison. |