|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 50

|

|

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

|

|

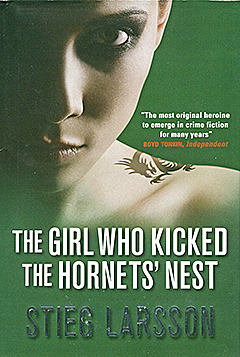

Note: Although The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest won’t be published here until May, demand for the English edition has been sufficient to rate a story in the December 7 New York Times (“Booksellers Feed Imports to Mystery’s Hungry Fans”). Thanks to a friend who had an extra copy, I didn’t have to fork over $45 for the British import, which I just finished. There will be no spoilers here, I promise.

Today is Jane Austen’s birthday. She was born on December 16, 1775. She died on July 18, 1817. What better way to begin a book review than by celebrating the author F.R. Leavis called “the first modern novelist”? While the surface gentility of her Regency milieu may appear out of place in the same column with a Swedish crime thriller written in the 21st century, the perceptual rigor with which she scrutinizes the society she’s holding in the palm of her hand carries an implicit force as strict in its way as your garden variety fictional blood and thunder, Gothic fireworks, shootings and knifings, heavy sex, or hand-to-hand combat. Mark Twain’s famous aversion to Austen could be read as a backhanded compliment testifying to the impact of her brilliance; it’s as if he were recoiling from a threat to his literary manhood. And if he found her characters so detestable, why did he keep reading her? “Every time I read Pride and Prejudice,” he once wrote in a letter to a friend, “I want to dig her up and beat her over the skull with her own shin-bone.”

Too bad Twain isn’t here to read about the latest raiding of the author’s tomb in Monday’s “Arts Briefly” column in the New York Times (“Austen Zombies Go Hollywood”), which tells us that in the movie of the best-seller Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Elizabeth Bennett “must survive vicious killers.” No problem: “Luckily Elizabeth and her sisters are all trained in the martial arts.”

The sort of novel Twain abhorred actually had more in common with the type Austen was referring to in a letter written four months before her death (“Pictures of perfection, as you know, make me sick and wicked”) and in her brief jeu d’esprit, “Plan of a novel according to Hints from Various Quarters,” where she imagines a “faultless,” beautiful heroine inhabiting a world in which “All the Good will be unexceptionable in every respect — and there will be no foibles or weaknesses but with the Wicked, who will be completely depraved and infamous, hardly a resemblance of humanity left in them.”

A Man With a Message

Since the subject at hand is The Girl Who Kicked the Hornets’ Nest (to be published by Knopf in May 2010), the third volume in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy (all three translated by Reg Keeland), a glancing reference to the author of Pride and Prejudice is not inappropriate. The original Swedish title of the first book in the series (and the film based on it), Män som hatar kvinnor (Men Who Hate Women), makes clear that Larsson was a writer with a message, and the terms used by Kate Moss in her Guardian review of the new book — ”a novel that is complex, satisfying, clever, moral” — suggest how far beyond the genre of a thriller his vision has taken him. In fact, the same terms would fit Austen’s fiction, as would the reviewer’s reference to the way “the theme of how words can be a force for justice permeates the narrative,” and the way “society chooses to treat those it does not understand.” The review goes on to point out that the women in Hornets’ Nest are “equal players — police officers, advocates, journalists — rather than just glamorous sidekicks or victims, as in so many thrillers.”

The women in Hornets’ Nest are more than “equal players,” however; they’re warriors. The book’s four sections are prefaced with lengthy epigraphs that underscore Larsson’s message by citing the 600 women “estimated to have served in the American Civil War”; the “fearsome female warriors from ancient Greece”; the Amazons of Libya where “only women were allowed to hold high office, including in the military (“Only a woman who had killed a man in battle was allowed to give up her virginity”); and the women’s army in West Africa whose survivors were interviewed and photographed as late as the 1940s.

Mark Twain’s fancy about digging Jane up and beating her with her own shin bone is nothing compared to what various men in the Millennium Series do or would like to do to Lisbeth Salander. At the end of The Girl Who Played With Fire, after shooting her in the head, her evil Russian father has Salander’s monster stepbrother bury the body, shin bones and all — but you can’t bury Salander. She’s as indestructible as she is indispensable. Without this force of nature at its epicenter, the trilogy would not be an international sensation that has people in the States lusting for the last (or is it the last?) installment.

A Startling Move

As promised, no plot spoilers are lurking in the dark corners of this review, but readers who want to see Salander in action may grow impatient, even though Larsson finds ingenious ways to put her unique genius into play. He also confounds our expectations by setting the stage for an explosive scene only to suddenly snuff it. Most writers in the thriller genre would light the fuse. Not Larsson, such is the depth of his commitment to larger themes. For a writer who has proven to be sensationally adept at manipulating his readers, it’s a truly startling and daring move.

The Other Plot

Meanwhile the latest twist of the real-life plot unfolding behind the scenes mirrors some of the Millennium Trilogy’s central preoccupations, most notably that of a woman jousting for justice against male adversaries in an implacable bureaucracy.

In 2004, not long after delivering the manuscript of all three novels to his publisher, Stieg Larsson died in Stockholm of a massive heart attack. He was only 50. The rumor that he’d been murdered was to be expected because of numerous death threats he’d received as the founder of the Swedish Expo Foundation, established to “counteract the growth of the extreme right and the white power-culture in schools and among young people.” As editor of the Foundation’s magazine, Expo (the model for the Millennium, the journal for which the series is named), he was instrumental in documenting and exposing Swedish far right and racist organizations. During the last 15 years of his life, he and his longtime (32 years) companion Eva Gabrielsson lived under constant threat from right-wing violence. According to an online article, “When a labor-union leader was murdered in his home by neo-Nazis in 1999, the police discovered photos of and information about the couple in the murderer’s apartment.” So it was not without cause that Larsson and Gabrielsson took “precautionary measures … were never seen together outside the house,” and “always kept the blinds down.”

The theory that Larsson was murdered has been denied by his colleagues, one of whom describes him online in terms of a heart-attack-waiting-to-happen. “A classic workaholic,” he put in long hours at Expo, wrote books on right-wing extremism, held lectures for international politicians, police forces and youths, not to mention writing the Salander novels at night and smoking 60 or more cigarettes a day.

Eva/Erica

One of the women warriors in Hornets’ Nest Erica Berger’s alter ego is Eva Gabrielsson, just as Larsson’s is her journalist colleague, best friend, and sometime lover Mikael Blomkvist. Erica and Mikael are the trilogy’s core couple, just as Stieg and Eva are the couple at the core of its creation. It seems more than probable that in the course of a close working relationship, Eva Gabrielsson played a part in the development of the saga and by all rights should be reaping the immense benefits from its worldwide success. In 2008, however, all of Larsson’s estate, including future royalties from book sales, went to his father and brother. Gabrielsson had no legal right to the inheritance because his will had not been witnessed, they were never married, and had no children. Since Swedish Law requires married couples to make their addresses publicly available, marrying would have been a security risk.

The most intriguing twist in the thickening plot is that Eva Gabrielsson owns the laptop containing the unfinished fourth book in the series as well as notes and outlines relating to it and future volumes. According to one source, Larsson told a friend that he’d written 320 pages of a book he expected to be 440 pages long; he had the beginning and the end but needed to flesh out the middle of the story. Clearly Gabrielsson would seem to be the person who, with some help from Larsson’s editors, could put together a legitimate fourth volume. Yet she can’t publish anything unless she’s given the full rights to manage the existing and subsequent novels in the series, something Larsson’s father and brother have refused to grant her. Last month she reportedly turned down their offer of a final settlement of two million kroner, claiming that it’s not the money she’s after, but the legal right to administer the literary property.

Gabrielsson, who is now 54, plans to publish a memoir, tentatively called The Year After Stieg. A website (www.support eva.com/uk) has been set up on her behalf to help with legal expenses. Though the negotiations have not yet put her in debt, she acknowledges that “three and a half years of this is expensive and sooner or later I will run out of funds or become unemployed, especially in these times of crisis. Then what do I do? Give up? No. You fight back. It’s what Stieg would have wanted.”

Talk about life imitating art. Not only is the situation right out of Larsson’s own fiction, it’s rich with the sort of social and moral challenges and complexities Jane Austen thrived on. As for life exploiting art, think about Elizabeth Bennett and her sisters karate-chopping those zombies as she tries to patch things up with Darcy.