|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 51

|

|

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 51

|

|

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

|

|

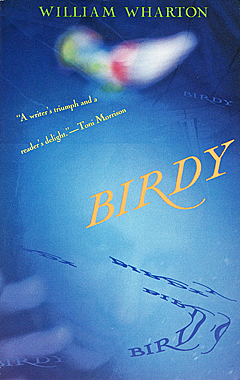

In the Fall of 1976 a literary agent based in Pennington received a novel in manuscript by way of a close friend and college classmate who had moved to Paris from Hopewell. The author was an expatriate American painter living in a houseboat on the Seine. Though he had a modest reputation as an artist, he was in his early fifties, unpublished, and, as a writer, unknown. The agent was so excited by what she read that rather than mail the manuscript, she took it in to New York personally, by car, and delivered it to an editor at Knopf, who read it and was equally excited. The first and only publisher to see the book, Knopf scheduled it for publication in Fall 1978, then held it back until January 1979 in order to avoid a major newspaper strike. With the press functioning again, the reception accorded the author’s first novel, Birdy, made him an instant literary sensation. The impact of his arrival on the scene could still be felt some 30 years later in the attention the press gave to his death. William Wharton, whose real name was Albert William du Aime, died on October 29, a little over a week short of his 83rd birthday.

Besides receiving extraordinary critical acclaim, Birdy became a best-seller, won a National Book Award, and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Meanwhile the agent, who became the author’s lifelong friend, was selling it to the movies and auctioning it to a paperback house for $525,000.

Compelling Belief

Birdy has to be read to be believed. Or, as Newsweek’s Peter Prescott put it while comparing the author to an alchemist, Wharton “compels belief.” So he does, but after you read this book, try telling someone in reasonably specific terms what makes it special and they will give you funny looks, as if you were putting them on. It’s not the notion of a character who wants to be a bird and tries to fly that’s hard to talk about with a straight face; the concept of a human metaphorically singing or soaring is nothing new to literature and mythology. Nor would it be all that much of a stretch to credibly communicate the possibility that a soldier obsessed with birds could be so traumatized by combat that his madness would take the extreme form that it does in Birdy. But how do you in simple conversation put across the idea that the heart and literary soul of an acclaimed novel depends on the reader believing that a boy not only falls in love with a canary but dreams himself into believing he’s become one, right down to mating with a female, nesting, and feeding nestlings? That would be a tricky feat even if the love object were a nightingale or a hawk, an eagle or a blackbird. But a canary? It might be different if you grew up with one in the house, or if your knowledge of the species didn’t begin and end with Tweetiebird. As Prescott’s review puts it (if you read “canaries” for “birds”), “Only the most rigorous imagination can make a story of this sort work for a reader who is generally indifferent to birds. Wharton has just such an imagination.”

Bringing off a book as unique as Birdy called for something more than a rigorous imagination; it required a comparable obsession in the life experience of the author. Like his title character, Wharton/du Aime grew up in Philadelphia and by the time he was 17 was overseeing a personal aviary of some 250 canaries that enabled him to make more money than his father could as a Depression-era carpenter. While Wharton, again like Birdy, saw combat in World War II, he came back with his faculties intact after being seriously wounded during the Battle of the Bulge. He studied art at UCLA, got a doctorate in psychology, and taught in the Los Angeles public school system for 11 years before moving to Europe with his family, eventually settling in Paris, where his wife taught and he painted and wrote. It wasn’t until the Hopewell-Pennington connection brought his novel to Knopf that he assumed a new name (combining his middle with his mother’s maiden name) and began a new life as a writer. His decision to use a pen name was his way of both masking his actual identity and keeping his two creative missions distinct. “In France, I’m just a crazy painter who lives on a boat,” he told one interviewer. “I didn’t want to become an American celebrity, even a small literary one.” In another interview he explained that “not thinking of myself as a writer gives me the freedom to be one.” The mask may also have permitted him to give his imagination even more play, in effect freeing him from the weight of his identity, like a lesser version of Birdy’s attempt to fly free of the weight of his human limitations.

Looking for Salinger

One odd side-effect of the pseudonym was that it helped inspire the absurd rumor that J.D. Salinger was sneaking into print by way of William Wharton (Salinger has been “outed” even more absurdly as Thomas Pynchon). There are, in fact, some parallels between the two writers worth mentioning. Salinger also fought in the Battle of the Bulge, undergoing a less idiosyncratic breakdown than Birdy’s, one that he made brilliant use of in “For Esmé — with Love and Squalor,” where the simple letterby-letter spelling out of f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s that are not (and finally are) “intact” creates the story’s denouement. A more likely hint for readers looking for a touch of Holden Caulfield in Birdy can be found in the voice or narrative style of Birdy’s best friend, Al, who provides the grounding essential to the book’s dynamic. While the chapters describing Birdy’s thoughts and “flights” are in italics, Al’s earthier, more profanely realistic point of view is laid out in good old no frills roman type. There’s an adolescent flavor to Al’s swearing that is occasionally, superficially evocative of Holden’s, but the clearest echo of The Catcher in the Rye’s ultimate message (“Don’t ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody”) comes when Al says, “Before you know it, if you’re not careful, you can get to feeling sorry for everybody and there’s nobody left to hate.”

If Al represents the voice of the street, or simply a more manly normality, the most striking of Birdy’s flights show Wharton attempting to articulate another world, to translate his art from the human to non human, to give voice to the very air, not merely in order to transcribe the song of a bird, but to virtually inhabit the bird and thus to become the song. Needless to say, this is a wildly ambitious undertaking, to move beyond the tropes and themes of poets writing odes to skylarks or nightingales or falcons. It was Wharton’s all-out attempt to live metaphor and enact analogy — to cross a line with seemingly nothing but madness or nonsense on the other side — that moved reviewers of the novel to employ terms like “a marvel,” “an amazement,” “a remarkable feat of the imagination,” “incandescent beauty,” “fascination,” or to impersonate the spirit of the novel with lines like “It soars” or “To read Birdy is to fly.”

Becoming the Song

An instance where Wharton shows us what he’s up to comes with his description of Birdy imagining a male canary’s mating song:

“There’s open air in his song, the power of wings and the softness of feathers …. It’s clear as any love song. He sings of things he could never have seen or known in the aviary …. These things must be memories in his blood carried through in his song. There’s the song of rivers and the sound of water and the song of fields and seeds in their natural places. It’s a song I’ll never forget. It’s with this song I began to understand something of canary. Canary isn’t a language like ours with individual words, or words put into sentences. In the singing, you let your mind go, not think, and it comes to you, clearer than words. It comes as if you’d thought it yourself. Canary is much more feeling, more abstract than any language. Listening…that night I found out things I knew must be but I’d never known. It was the song of someone who knows how to fly.”

Although the passage suggests that Wharton is resorting to the same limited language a poet, however gifted, might use, what makes Birdy’s achievement believable is the way Wharton carefully, almost methodically, prepares the reader for it. The transformation doesn’t happen all at once. It’s what Peter Prescott is getting at when he observes that Wharton is aware that “to draw us into Birdy’s world of illusion he must begin with precise descriptions of how birds behave and then must modulate to the more rarefied stuff.”

That “stuff” is no less rarefied today than it was 30 years ago. What’s surprising is how hard it is to find a copy of Birdy, even though it’s still in print in a Vintage paperback. As of this writing, the Princeton Public Library has nothing by William Wharton on its shelves.