|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 6

|

|

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

|

|

|

He is the author of a multitude of good sayings, so disguised as pleasantries that it is certain they had no reputation at first but as jests; and only later, by the very acceptance and adoption they find in the mouths of millions, turn out to be the wisdom of the hour. I am sure if this man had ruled in a period of less facility of printing, he would have become mythological in a very few years, like Aesop or Pilpay, or one of the Seven Wise Masters, by his fables and proverbs.—Ralph Waldo Emerson, April 19, 1865

Some 20 miles to the west of the southern Indiana back woods log cabin Abraham Lincoln grew up in is the town of Princeton, home of a wool-carding mill he delivered wool to one day in August 1827. The 19-year-old Lincoln spent one night in Princeton. One night only. More than three decades later, President Lincoln was visited at the White House by a man who owned a store in Princeton. According to the WPA Guide to Indiana, Lincoln instantly knew the man’s name, the store, and the town: “‘Oh yes,’“ he said, “‘I remember the name as the one I saw on a sign in Princeton …. It was the first gilt-lettered sign I had ever seen and it attracted my attention.’ “

You have to think that the store owner’s jaw must have dropped at this detailed recollection from a busy president who had been to the town in question, our Indiana namesake, only once in his life. Perhaps that’s why Lincoln felt he needed to downplay his feat of memory with a reference to the gilt-lettered sign. It’s also possible there was a more colorful explanation that might not have gone down too well in a White House reception line (certainly not if Mrs. Lincoln was within earshot). According to a footnote in Michael Burlingame’s The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln (1997), Lincoln’s attention had also been attracted by the Princeton mill-keeper’s niece, one Julia Evans, whose “beautiful face and figure” had “thoroughly captivated” him.

Rare Abe! True or not, the mere surfacing of such a story suggests why he’s the most beloved of American heroes. While he undoubtedly possessed “a phenomenal memory,” as Douglas L. Wilson notes in Honor’s Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln (1997), the beauty of Lincoln is that wherever you turn, it’s not his memory but his humanity that touches you. Isn’t this why he’s so often spoken of in the most familiar terms? Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton play the first-name game, but no serious historian or observer is going to casually refer to “Jimmy” or “Bill” the way Herman Melville writes of Lincoln in a letter to his wife in March 1861 describing a White House reception: “A steady stream of twos & twos wound thro’ the apartments shaking hands with ‘Old Abe’ and immediately passing on …. Of course I was one of the shakers. Old Abe is much better looking than I expected & younger looking. He shook hands like a good fellow — working hard at it like a man sawing wood at so much per cord.”

Four years later in “The Martyr,” Melville would write one of the most passionate responses to the assassination (“When they killed him in his prime/Of clemency and calm —/When with yearning he was filled/To redeem the evil-willed,/And, though conqueror, be kind”).

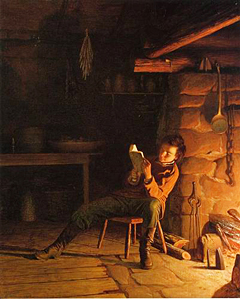

Reading by Firelight

In The Boy Who Loved Books (2003), a children’s book by Kay Winters, Nancy Carpenter’s illustrations show beanpole Abe reading perched high up in a tree and then with a book in one hand, one hand on the axe-handle, when taking a breather from log splitting. (The image used here is a reproduction of Eastman Johnson’s painting, The Boyhood of Lincoln.) Various witnesses from the time tell of Lincoln reading while standing, while sitting on a pile of logs, or walking down the street with the book open in his hand, or leaning back on a cellar door, or even while “lying on a trundlebed rocking a cradle with his foot.” The most hallowed and seductive image, however, is of the boy reading by firelight beside the hearth in that storied log cabin. Kids grow up associating George (nobody calls him “George”) Washington with the chopping down of the cherry tree (“I cannot tell a lie”) and its built-in moral. There’s no moralizing in the legend of the boy reading by firelight. Such sight-challenging devotion sheds glory both on the activity of reading and the value of books. If you’re at all inclined to read at an early age, Lincoln’s example inspires you, particularly when you live within an easy schoolbus ride of that very cabin.

What led me to the anecdote about Princeton, Indiana, in fact, was a hard copy map quest to see where my hometown, Bloomington, is situated in relation to the hallowed site. While it may be a little farther than I thought, it’s close enough to explain my fourth-grade feelings of connection with the boy who grew up to be Lincoln. For me, this was not a remote figure, nor the saviour of the Union, nor a chapter in a history book — not when I was riding a schoolbus through a back woods wilderness in the same part of the state every morning and doing my reading in a two-room schoolhouse with water drawn from a well and an outhouse in back, and a traveling book truck providing material that of course included child-focused biographies of Lincoln. When I finally saw the log cabin on a school trip, I may have been told that it was a reconstruction, but that didn’t make the moment any less powerful. There it was, the hearth real enough to touch and set your foot on, as real as the boy who had hunkered down there with a book.

What makes Lincoln Lincoln is that he wasn’t merely reading for the sake of reading. He was educating himself. From all accounts, this most eloquent and literate of presidents had no more than a year of actual supervised schooling. In the most recent full-scale biography, Princeton Ph.D. Ronald C. White, Jr.’s A. Lincoln (Random House 2009), as well as in Honor’s Voice, various witnesses describe Lincoln’s diligence, including his stepmother, who said that “Abe read all the books he could lay his hands on” and when he came across a passage that struck him, “he would write it down on boards if he had no paper & keep it there till he did get paper — then he would re-write it — look at it — repeat it.” He also had “a copy book — a kind of scrap book in which he put down all things and thus preserved them.”

There’s a scene in John Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) when Henry Fonda in the title role of the young lawyer digs excitedly into a stash of books in the back of a covered wagon belonging to a family that had no money to pay him for defending their son. Books being better than money, he takes a copy of Blackstone’s Commentaries for his fee and settles down flat on his back by the riverside, in true Lincoln style, to devour it.

Lincoln and Shakespeare

Accounting for the roots of Lincoln’s “moral integrity,” Ronald White mentions “the soil, Shakespeare, and the Bible,” and the more I read about Lincoln’s self-education, the more Shakespearean he seems, not because of the dramatic magnitude of his story, but according to the question that has vexed scholars and readers of Shakespeare through the ages. It seems no less improbable that a spirit and intellect like Lincoln could emerge from his backwoods world, the son of a farmer and a carpenter, than that an unschooled glovemaker’s son could write Hamlet. In that sense, Lincoln is America’s Shakespeare. Seen purely in terms of one’s impact on the national imagination, who else but Lincoln? Not Ben Franklin, nor Emerson, nor Melville, nor all of them put together. Figures don’t lie. In 2002, Lincoln finished fourth, after Jesus Christ, Shakespeare, and the Virgin Mary, in a WorldCat search for books about famous people in an online worldwide library catalogue (he had 14,985 entries to Shakespeare’s 35,904).

For a sample of the bite of Lincoln’s Shakespearean wit, check out this passage from a speech at a Republican banquet in Chicago a month after James Buchanan was elected president in 1856: “The President thinks [that we], being ardently attached to liberty, in the abstract, were duped by a few wicked and designing men. There is a slight difference of opinion on this. We think he, being ardently attached to the hope of a second term, in the concrete, was duped by men who had liberty every way. He is the cat’s paw. By much dragging of chestnuts from the fire for others to eat, his claws are burnt off to the gristle, and he is thrown aside unfit for further use. As the fool said to King Lear, when his daughters turned him out of doors, ‘He’s a shelled pea’s cod.’ “

For the past week, looking ahead to tomorrow, the 200th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth, I’ve been reading around in a number of the books, some not yet counted, among the 14,985 reported by Gerald J. Prokopowicz in his amusing collection of answers to the questions he’s heard as scholar in residence at the Lincoln Museum, Did Lincoln Own Slaves? (Pantheon 2008). (The WorldCat search must also have turned up a multitude of books about Charles Darwin, born 200 years ago on the same day as Lincoln.) The passage from Lincoln’s speech came from a book published in 1904, Letters and Addresses of Abraham Lincoln, and can also be found in Lincoln, Speeches and Writings 1832-1858, in the Library of America. As I’ve suggested, I found special interest in the chapters about Lincoln’s self-education in both White’s A. Lincoln and Wilson’s Honor’s Voice, the subtitle of which is particularly suggestive, if you think of the “transformation” in the context of the mystery. We know vastly more about Lincoln than about Shakespeare and yet the question remains, “Where did this extraordinary being come from? How could America have produced such a man at such a time?”