|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 7

|

|

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 7

|

|

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

|

|

Look out, the Oscars are coming. Besides being the handiest excuse for hyping a product this side of the Christmas season, the Academy’s big night is a Great American Event right up there with the World Series, the Super Bowl, and presidential campaigns.

Heath Ledger

To state the obvious, the Academy selection process has often been compromised by in-fighting, box office clout, political correctness, and prevailing winds of sentiment. When Heath Ledger died at 28 late last month from an apparently accidental overdose of prescription drugs, one of my first thoughts was that he should have won the Best Actor Oscar in 2005 for his portrayal of Ennis Del Mar in Brokeback Mountain. Given the Academy’s long-standing by-the-book concept of good acting, it’s no surprise that Philip Seymour Hoffman’s turn as the gay author in Capote would beat out Ledger’s lonely, love-embattled gay sheep herder. Hoffman’s brilliant delineation of Capote was so “textbook” you could almost see the inventory of effects: the lisp, the body language, the limp hand gestures, the mischievous ambience; it was work of transparent virtuosity from an admirably versatile character actor masquerading as a literary operator of seasoned charm. Hoffman’s commitment was essentially cool, calculated, and intellectual, but not particularly compelling. Heath Ledger’s heartbroken, heartbreaking Ennis Del Mar stays with you after you leave the theatre. Hoffman played Capote, in every sense of the word; he was performing a performer. Ledger lived Ennis Del Mar. It’s the difference between one actor’s subtle, deep, even painful bonding with a fictional character and the other actor’s commanding impersonation of a real-life celebrity, a known human quantity.

If you have a chance to see Heath Ledger as the title character in Casanova, which was released immediately after Brokeback Mountain (attention to its Venetian splendor possibly obscured by the other film’s extraordinary reception), you’ll not only have fun watching a movie said to be the first one ever wholly filmed on location in Venice, you’ll realize how much we lost last month. Ledger had the old-school movie genius that film buffs refer to when using terms like “star power.”

Academic Limitations

Oddly enough, or maybe not oddly at all, “star power” is something the Academy has often either misjudged or overlooked on awards night. A glance back to the so-called Golden Age reveals little or no recognition of the stars and movies that have come through the decades as posterity’s choice, the classics, the immortals, the Garbos and Chaplins, Freds and Gingers, William Powells and Myrna Loys, not to mention the likes of Cary Grant, John Wayne, Judy Garland, Margaret Sullavan, Barbara Stanwyck, or directors Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Ernst Lubitsch, Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, or the great movies of the era from City Lights and Scarface to Citizen Kane. Even when the Academy gives the prize to a James Cagney or Spencer Tracy or Bette Davis or Katherine Hepburn, it’s all too often for more “academic” performances than the ones that have endured.

What it comes down to is the Academy’s primal notion that superior acting and superior films have to be Serious. Accordingly, the film noir, the romantic comedy, the love story, the pure comedy, the western — the genres that are the very heart and soul of American film — play second fiddle to the “Serious Work.” Which means that the Academy has given preference to biopics of Gandhi, Emile Zola, Louis Pasteur, or Madame Curie, or bloated epics like Ben Hur, or filmed plays like Cavalcade or Amadeus, while ignoring true classics like The Thin Man or Top Hat or My Man Godfrey or My Darling Clementine or any number of other genre treasures. With an exception about to be mentioned, “Light” usually loses out to “Straight.” Take 1932-33, when the Best Picture went to Cavalcade, which comes off looking stiffly “acted” and dated today. The winning performances were Acting-with-a-capital-A emotings of Charles Laughton and Katherine Hepburn that now look stagey and dated compared to the lively ensemble playing in Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, which was released during the same period and illuminated by the presence of stars such as Herbert Marshall, Kay Francis, and Miriam Hopkins. Compare Hepburn’s lovely but super-precious Oscar-winning performance in Morning Glory with her more inventive and free-spirited later work in Bringing Up Baby, Howard Hawks’s inimitable screwball comedy. By all rights, Baby should have swept the Top Four in 1938. Hepburn and Cary Grant gave the performances of their lives under the guidance of Hawks, who should have a closet full of Oscars and was only nominated once — and then for a biopic and one of his least inspired films, Sergeant York.

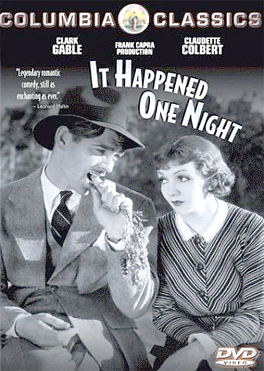

Given the Academy’s preference for Serious Drama, it’s no wonder a screwball comedy like Bringing Up Baby was bypassed in 1938, but then what to make of the fact that a comedy did win for Best Picture that year? While Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take it With You had its share of screwballs, too, look what else it had going for it: the clout of Broadway prestige (it was based on the Pulitzer-prize-winning play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart) and Capra’s Academy stature, earned on the strength of the miracle sweep of 1934, the ultimate exception to the Straight-trumps-Light rule, accomplished when It Happened One Night became the first film to sweep the Big Four — a feat not to be matched for 40 years. You could call this road romp about a cynical reporter and a spoiled heiress The Gone With the Wind of comedy romance, except that it’s a better movie, and it came out of nowhere, from a poor-relation studio, Columbia, to win Best Picture, Director, Actor, and Actress, with the stars, Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, coming along for the ride. Only two other movies have copped the top four honors: in 1975, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and in 1991, The Silence of the Lambs.

Like everyone else on Oscar night, I sometimes think about what my own choices would be, not for this year, but over the whole span from 1927 on. Needless to say, I rarely agree with the Academy, 1934 being a large exception. Another year I’m in general agreement with is 1946 when the awards were dominated by William Wyler’s film about three soldiers coming home, The Best Years of Our Lives. The only problem is that Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life also came out that year. Frederic March, an actor’s actor, was a worthy choice for Best Actor, but James Stewart, a star’s star, gave possibly the greatest performances in Hollywood history in Capra’s masterpiece. March’s magnificently felt portrayal of the war-haunted bank director is right up there, but it can’t match the energy and passion of another banker, Stewart’s George Bailey. No doubt the Academy saw the realistic portrait of postwar America in Years in positive contrast to the Dickensian fantasy America in It’s a Wonderful Life. In fact, serious film people still make faces at what they see as Capra’s sentimental claptrap and the whimsical nonsense of that icky-cute angel played by Henry Travers. The whole weird reverse Christmas Carol fandango is too much for them. No use arguing that when you have a masterfully directed movie driven by a performance the ad writers could justly call “towering,” you can play fast and loose with reality and get away with it.

Princeton’s Star

One of the most laughable misnomers in American film is the stereotype of James Stewart as the drawling, aw-shucks-ma’am regular guy. Among all the Hollywood stars, this Princeton graduate (a Class of 1932 architecture major) is the most passionate of players, doing award-caliber work in the Anthony Mann cycle of westerns, and with directors such as John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock, and in films ranging from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington to The Shop Around the Corner to The Mortal Storm. How typical, then, that the Academy would allow him his lone Oscar, in 1940, for a lighter role he simply breezed through, in The Philadelphia Story. And look who got the Oscar in 1959, the year when you’d have thought no actor on the planet could come close to Stewart’s portrayal of the fisherman lawyer in Anatomy of a Murder — Charlton Heston in Ben Hur. So it goes, and will always go, with the Academy.

You can find most, if not all, of the above mentioned films on DVD at the Princeton Public Library.