| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

"ONLY FOR TWO": One of Eleanor Burnette's contributions to "Twenty Years--Part II" at the Virginia Lynch Gallery. |

Making the Most of Life: A Portrait of the Artist

Stuart Mitchner

Eleanor Burnette has truly lived her art. Like most artists, she is an inspired opportunist. From an early age, she found material everywhere. The mud in a Chicago backyard yielded interesting shapes in her hands. Then she was told little girls were not to play in mud. Years later she was building forms in clay. Little girls were also not supposed to stay up well past their bedtime moving a pencil over sheet after sheet of cheap, invitingly raw paper trying to capture a fascinating image. For the better part of thirty years now, this artist is still pursuing tantalizing images and still finding material everywhere.

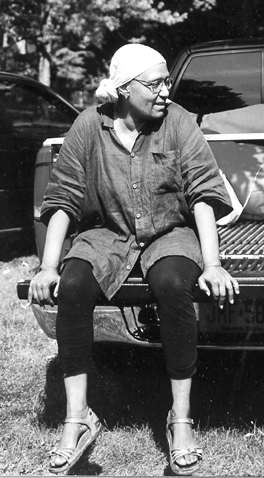

The material may even be the artist herself. Diagnosed with breast cancer in February 2001, facing a radical mastectomy, she opted for reconstructive surgery, becoming human clay for a plastic surgeon who has since become a friend and supporter. Facing seven hours of surgery and weeks of recovery, she made sure to have several projects underway so that when the time came she could get right back to work. Six months after the operation, she had put together a solo exhibition at Ellarslie, the City Museum of Trenton, featuring, along with figurative bronze sculptures from an earlier period, a striking series of unconventional portraits grouped under the title "Unlikely Saints." In the photo shown here, the artist cools her heels on the flat bed of her pick-up truck with her sleeves rolled up and sporting her chemotherapy head-scarf, tired but happy, having just unloaded and set up the show.

HOW SWEET IT IS: Cancer survivor Eleanor Burnette relaxes with a smile and a sigh after setting up her August-September 2001 solo exhibition at Ellarslie, the City Museum of Trenton. |

After Her Recovery

The work done after her recovery earned Ms. Burnette a fellowship to the Vermont Studio Center where she painted the pieces (she prefers "constructed" to "painted" – "I am a sculptor who paints") that were featured in her first New York exhibit at the UFA Gallery in January 2003. Through January 18, two of her paintings are in a 20-year gallery retrospective at the Virginia Lynch Gallery in Tiverton, R.I. The roster of distinguished artists her work is being shown with includes Jules Olitski, Chuck Close, Wolf Kahn, and Robert Motherwell.

While she says she drew no explicit lessons from living through major illness ("You can't know, and don't need to know, how something like that affects your work"), Ms. Burnette clearly has come back to her art with renewed energy, giving special attention to images associated with her African-American heritage, like the frieze of Middle Passage figures in her mixed-media-on-paper abstracted ship bearing its human cargo (White Seas, Less Light).

Cancer may have made her more constructively attuned to buried images than she otherwise would have been, but the instinct to discover them (the opportunist artist again) can be traced back to those after-bedtime sessions in childhood. "I was obsessive about it," she says, citing her fixation on a particuar figure, that of a girl diving. Something in the angle formed by the dive fascinated her. The pages piled up. She was already doing what she would do as a mature artist in the studio, laboring over drafts and layering her work. But why the figure of a diver? Perhaps she was seeing an image of herself and her art plunging into the element in which she would flourish at school ("The Art Room was heaven!").

Her seventh-grade teacher picked her to represent the school at a Saturday art curriculum for gifted children at the Art Institute of Chicago. For two years the long bus ride to the Institute from the far South Side was a weekly journey toward independence; she was on her way, free to dream, to fill her eyes with the imagery of the city, to know that she was no longer the child who had been told that little girls didn't play in the mud.

Artist or Doctor?

Even so, she considered becoming a doctor, entering college as a pre-med, but it wasn't until 1976, after marriage and a child, that she graduated in fine arts as an adult learner at Chicago State University.

When she landed in Princeton in 1978, she took advantage of some free studio space in the the basement of a house on Murray Place, living out the struggling-artist storyline by clandestinely spending her nights there as well. She worked for a time at the nearby Carousel luncheonette; next was the salad bar in an early incarnation of Chuck's on Spring street.

Then a major opportunity came her way, at Micawber Books, where, in addition to designing window displays that caught the eyes of Nassau Street strollers, she became one of the store's most personable and durable sales people. Except for an interlude working elsewhere and studying at Rhode Island School of Design, she has been at Micawber since the early eighties. Just as she gives life to her art, this artist with a gift for life brings the same qualities to her bookstore work. Besides making invaluable contacts in the community, she's put her expertise to work ordering books in the arts and humanities.

It was while Ms. Burnette was living in Rhode Island that she began her relationship with the Virginia Lynch gallery. Trying to define the quality in her art that people seemed most responsive to, gallery-owner Lynch stressed her sensitivity. "She's one of the most sensitive people I've ever known. She's also sensitive to what she's painting and that carries through in her work."

One of the paintings displayed in the gallery (Only For Two) continues her exploration of the Middle Passage theme and is constructed in a way that makes you feel you are looking at cave or temple art. The figures have a rounded, three-dimensional quality and a rough texture, like stone worn by time and the elements. At once primal and enigmatic, this very constructed painting conveys something stronger than just sensitivity.

Middle Passages

Semblances of the Middle Passage figures show up again and again in variously constructed and titled works: not only in the bowels of a ship, but on a bridge, on grey heights, in rich red waves, and in other interestingly titled paintings (Contained, Two Avenues, Eaten Alive). In her quest to know more about this aspect of African-American history, the artist bought and studied books on the slave ships, as well as publications like Callaloo, A Journal of African Diaspora Arts & Letters, which reproduced a painting of hers for one of its covers.

When asked about the apparent link between the obsessive drawings of a single image she did as a child and these seemingly obsessive variations on a theme, she sees a connection in terms of the process she still follows: layering, building, sculpting with paint and mixed media, and improvising on a recurring generic image. As an example she mentioned 40 or 50 India ink line drawings of people she did in the late 1970s, not from life but as she imagined them. She feels so close to one of the pieces she refuses to sell it. "People think it must be a self-portrait, but it isn't," she said.

She has revisited and reinterpreted the image many times in the years since, enlarging it, abstracting certain aspects like the hair and the mouth, using it as a template. Her bond with it must have to do with something more than its usefulness. Perhaps it represents the DNA of her art, the essence of all the material she has shaped with her hands since a little girl dipped them in the mud of a Chicago back yard. Eleanor Burnette's work will be part of a group exhibition, "Glimpses of America," at the Carriage House Gallery in Cape May, from January 17 through April 11.