|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 3

|

|

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

|

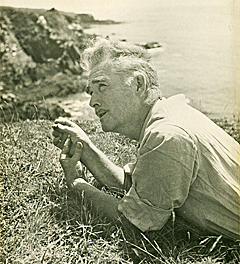

BLACKMUR ON THE CLIFFS: R.P. Blackmur, by all accounts, drank and talked and smoked a lot. You can see the stub of a cigarette he’s holding in the accompanying picture, taken on the cliffs at Cape St. Mary in Nova Scotia by Princeton English Professor E. D. H. Johnson’s wife Laurie, whose photographic portraits are in the archive of the Historical Society of Princeton.

|

The art of poetry is amply distinguished from the manufacture of verse by the animating presence in the poetry of a fresh idiom; language so twisted and posed in a form that it not only expresses the matter in hand but adds to the stock of available reality.R.P. Blackmur

Born 105 years ago today, January 21, 1904, R.P. (Richard Palmer) Blackmur lived in Princeton from 1940 until his death in 1965. To Edward Said, he was “the greatest genius American criticism has produced,” while R.W.B. Lewis called him “one of the best critics of poetry who has ever lived” — ”To find a critic in England as competent to get inside the actual language of poems and detect its unique activity (not merely its color and flavor), one probably has to go back to Coleridge.” Lewis points in particular to “Blackmur’s ability to describe a poem as an event, a happening — an act of creation, of bringing into being not only a meaning but a reality.”

It seems a misnomer to speak of literary heroes like Coleridge or Blackmur in terms as antiseptic and as far from Blackmur’s notion of a created reality as “critic” and “criticism.” Venture at random into the world of Blackmur’s prose and you can find a sentence on every page that expresses his true calling, which is to write so vividly about literature that he makes you crave the reading experience, even if it means going out into a snowstorm to lay hands on the work in question (something that may no longer be necessary if Google succeeds in putting all literature on the head of their virtual pin). Anyway, the greatest so-called “critics,” the Blackmurs and the Coleridges, can convey their excitement as readers so effectively that you seldom feel the need to go back to the original, the essence of it having already been communicated.

If you tend to at least half-believe the stereotype of academia as somehow opposed to “real life,” it’s worth pointing out that, like Coleridge, Blackmur never received a college degree. In fact, he never graduated from high school; he was expelled, which gave him time to indulge the passion for reading that led to his becoming managing editor and a major contributor to Hound and Horn, one of the most respected “little magazines” of its time. The intensity of that passion — his “fire in the belly” for books and the ecstasy of reading — comes through in his introduction to Henry James’s The Wings of the Dove, which he discovered at the age of 17:

“When I was first told, in 1921, to read something of Henry James … I went to the Cambridge [Mass.] Public Library …. The day was hot and muggy, so that from the card catalogue I selected as the most cooling title The Wings of the Dove, and on the following morning, even hotter and muggier, I began, and by the stifling midnight had finished my first elated reading of the novel. Long before the end I knew a master had laid hands on me. The beauty of the book bore me up; I was both cool and waking; excited and effortless; nothing was any longer worthwhile and everything had become necessary. A little later, there came outside the patter and the cooling of a shower of rain and I was able to go to sleep, both confident and desperate in the force of art.”

There it is in action, that “animating presence” informing “the stock of available reality” when an author lays hands on you, bears you up, cools you, wakes you, excites you, drains you and exalts you to such a degree that the force of the experience makes you desperate. In fact, the paragraph on the “art of poetry” containing that phrase actually “laid hands” on the poet John Berryman. As the future author of Dream Songs and Homage to Mistress Bradstreet once admitted, “It changed my life,” something Blackmur materially did by bringing the constitutionally desperate Berryman to the Creative Writing Program at Princeton at a time when he was out of work and out of options.

Wartime in Princeton

Although everyone who knew the Blackmurs seems to agree that their marriage was not a happy one, they make a formidable and fascinating couple in Berryman’s wife Eileen Simpson’s book, Poets In Their Youth (a joy to read for anyone with a fondness for literature, enlightened gossip, and Princeton). A painter, Helen Blackmur abandoned her attic studio on Prospect Avenue to take a wartime job as the supervisor on the second shift in a Trenton factory making airplane parts. The Blackmurs lived in an apartment (eventually sublet to Saul Bellow) in the big ramshackle frame house on the northwest corner of Princeton Avenue and Aiken, and if you know that street and that house, it’s nice to imagine Helen Blackmur coming home from the factory at midnight in overalls with her “workman’s metal lunch box.” According to Simpson, the factory job “served a dual purpose.” For one thing, “the war effort permitted her to dramatize her rebellion against the role of faculty wife: A worker in overalls does not pour tea and play hostess.” When T.S. Eliot came to town, and Blackmur told his wife “somewhat diffidently, that he had invited the Great Man to dinner, she snapped, ‘Tell him to bring his own chop.’” She also had a low tolerance for academic rhetoric, and once when Blackmur was “ruminating about the Nature of Man,” she “cut through his monologue with, ‘Man? Man is just a hunk.’” Molly Bloom (and Nora Joyce) would have loved her.

It was quite a time and quite a place, with the Blackmurs at 12 Princeton Avenue, the Berrymans in the four-story, red-brick building at 120 Prospect Avenue, Jacques Maritain around the corner on Linden Lane, and Allen Tate and Caroline Gordon housed a few blocks away on the corner of Nassau and Riverside.

Blackmur at the Butcher’s

Simpson confesses that Blackmur’s appearance had somewhat surprised her. Instead of the image based on Delmore Schwartz’s account of Bohemian days in Boston and photos showing Blackmur “wearing a flowing Byronic tie and looking pale and poetic,” Simpson found that “the wild poet” was hidden behind the “public face” of the man who introduced her to the shops of Nassau Street on one of her first days in Princeton: “Short and solidly built, he wore a fedora with an ever-so-slight tilt to one side, well-pressed tweeds, a conservative tie, and highly polished brown shoes. With his graying hair [at 39] and trim gray mustache, he looked more like … the man of distinction in the whiskey ad than a writer.” As he showed her to “the right greengrocer” and “the right butcher,” he would tip his hat “to Princeton matrons” and stop to greet and introduce her to professors while “dawdling at every window on the way.” At the butcher, Vogel Brothers, he discussed the weather, the news, the meat business, what the wealthy customers in the west end of town were ordering, what Mrs. Dodds (the wife of the president of the university) was having for Thanksgiving, the finicky eating habits of Helen’s cats [two Persians], and Mrs. Vogel’s operation.”

After describing “the Leopold Bloom of Nassau Street’s” tour through the commercial end of Princeton’s “stock of available reality,” Simpson concludes that Blackmur “needed people the way he needed cigarettes, rum, and strong coffee. He needed conversation, he needed an ear for his monologues, he needed chat.”

And he needed that walk. In his essay, “A Critic’s Job of Work,” which he begins by defining criticism as “the formal discourse of an amateur,” Blackmur brings in the everyday notion of the activity he shared with Eileen Simpson that day on Nassau Street: “Like walking, criticism is a pretty nearly universal art.”

The books by R.P. Blackmur I’ve consulted are Studies in Henry James and The Double Agent, both of which “turned up” for me on Nassau Street at Micawber Books. Poems of R.P. Blackmur is available at the library, as is an extremely heavily read copy of Poets in Their Youth. Perhaps with a little prodding the library will order what seems to be the most recent collection of his prose, (Outsider at the Heart of Things), or his Selected Essays, which, like the Poems, is edited by Denis Donoghue. Books about Blackmur include Russell Fraser’s biography, A Mingled Yarn, and The Legacy of R.P. Blackmur, edited by his Princeton University colleagues Edward T. Cone, Edmund Keeley, and Joseph Frank.

Poe’s 200th

R.P. Blackmur also wrote the afterword to the Signet edition of The Fall of the House of Usher and Other Tales by Edgar Allan Poe, whose 200th birthday Monday was somewhat overshadowed by that of Martin Luther King (actually born January 15). Poe has serious Princeton connections (as in in Poe Field and Poe Road) because of the brothers Poe, all six the offspring of Poe’s cousin, John Prentiss Poe (Class of 1854) and all sports heroes for Old Nassau, where Poe’s namesake, Edgar Allan (1891), was a football All-American in 1889. Nor was Poe himself a stranger to sports. Legend has it that he once swam across the Chesapeake Bay.