| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

caption: |

Dancing on the Edge: Will Barnet and Bob Blackburn at the Mason Gross Galleries

Stuart Mitchner

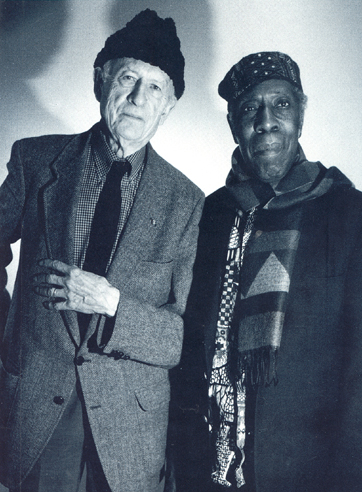

Here's a photograph worth more than a thousand words. You could spend that many pondering whatever zigzag patterns of circumstance and personal history might have placed the white man in the tweed jacket next to the black man with the extraordinary scarves. You could explain the pairing with one word, "Art," but the most satisfactory explanation can be found in the work of Will Barnet and Bob Blackburn now at the Mason Gross Galleries in New Brunswick under the title, "An Artistic Friendship in Relief."

The photograph shows Will Barnet, "a living American treasure" in the words of exhibit curator Judith K. Brodsky, standing shoulder to shoulder with his colleague and friend of fifty years, master printmaker Bob Blackburn, who died in 2003. No matter how taken you may be with the art that has been so sympathetically and effectively arranged here, you will probably leave the exhibit with this image of the two men foremost in your mind. For one thing, it offers some insights into the contrasting styles of both artists. Mr. Barnet's tweed jacket and checked shirt are in sharp relief, as are the five remarkable large works of his displayed on what might be called the exhibit's main stage.

The broader, bolder shapes in Mr. Blackburn's elaborately figured scarves have a flair reflected in the patterns, colors, and visual rhythm of his lithographs Root Toot and Color Symphony. Then there's the headwear: the black astrakhan hat like the solid black shore in a Barnet landscape, the patterned cloth cap a Blackburn jeu d'esprit waiting to be printed. As for facial expressions, the contrast is not quite so pronounced, although Barnet looks to be on the verge of a smile while Blackburn seems the brooding embodiment of the blues.

caption: |

Speaking of his friend at last Saturday's gala celebration of the exhibit, Barnet quoted Blackburn's statement that "the work must dance on the edge of the abyss," and then added, with a smile, that the same could be said of Blackburn's life. Even so, Blackburn's prints are playful and lively and dance to a rhythm of their own. In the context of music, abyss or no abyss, the man swings.

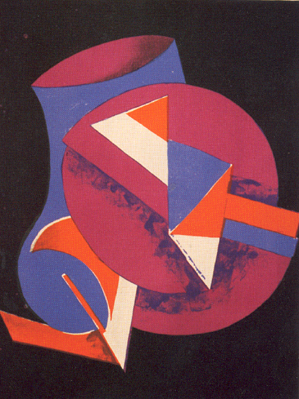

Based on the evidence, the aesthetic relationship between these two artists is most visible in the abstract prints Barnet made in the 1940s and 1950s, some of them done in Blackburn's printmaking studio where, according to one critic, Barnet's "colors softened and glowed." When speaking of him on Saturday, Barnet amusingly recalled his friend's total fixation on "the stone," meaning the lithographic stone from which Barnet's lithographs absorbed that soft glow. Considering the fact that Blackburn's Printmaking Workshop was, according Barbara Lekatsas's introduction to the exhibit catalogue, "the foremost artist-controlled" workshop in New York, there must have been some serious magic in that stone.

While all Blackburn's work on display here, and perhaps half of Barnet's, can be defined as "abstract," the term seems inadequate when you look at Blackburn still-lifes like The Mirror (Reflections), Table, or Red Pitcher, in which recognizable objects are in flux rather than wholly detached from "real life" identities. In this case it's not only the edge of the abyss Blackburn's work is dancing on but the edge between abstraction and representation, fiction and non-fiction. Lithographs like Grey Wood and Blue Screen simply defy terminology. Blue Screen has more to do with urban blues and urban moods than textbook nomenclature would allow. Music, in fact, is the alter ego of Blackburn's best pieces. Titles like Faux Pas, Curly Q, Quiet Instrument Odd Ball, Root Toot, and Colored Symphony make you listen as you look.

It's only fair to locate Blackburn's "abyss" in the context of the statement it concludes. He was talking about "a hierarchy of relationships in which the mind, thought, expressiveness, imagination, mystery, and magic are dreams of the artist" and that "to become a breathing life force, the artistic ingredient must be felt rather than just used as a display of surfaces, textures, and colors – beautiful but lacking substance."

Blackburn's pronouncement makes a fitting introduction to the severe but substantial beauty in his friend Barnet's serigraphs and lithographs from the 1970s and early 1980s. Again, the standard terminology seems inadequate. Words like "realism" or "representation" or "abstraction" fall short when the forms in question are at once stylized and human, and at the same time so revealing of the creative process that the structural abstract of the work is there to be seen even as you appreciate what the images represent. However flat and fixed and perfect these works may be, they are in process in the sense that the artist is distinctly outlining all the formal elements so that if you choose, you can subtract the "reality" of cat or woman or tree or bird or book and simply see through to the pure form.

The biography of most artists lumped under barely adequate terms like "modernism" usually proceeds from the drawing or painting of recognizable subjects to a gradual disappearance into whatever departure from or variation on realism the artist chooses. Will Barnet subverts that sequence. While the samples of his work from the mid-1930s displayed here clearly represent their subjects (a boy, a girl, people picking cotton, a mother reading to a child), an aquatint/etching from 1936 (Norwalk) hints at things to come. It's a street scene with two or three human figures in it, but the forms are broken, and the image seems to be imploding even as you look at it. Barnet's works from the 1950s are inarguably abstract, more so than most of Blackburn's. Wine, Women and Song, a color linoleum cut from 1958, can be read any way you want. It's pure pattern. In The Cat you can look for one, the hints are there, but the fun of the lithograph is in the absence not the presence of cat. Call It Winter, another color lithograph from the same period, is really saying "call it anything." Jump to 1970 and what you see is – or at least seems to be – what you get.

caption: |

The serigraph, Woman Reading, really shows a woman reading. And that's a very definite cat curled up with her, and a very definite book in her hands. But you can't simply label it "representational." Look at the woman's eyes: you can see she's not reading, she's looking elsewhere; she may even be aware that she is what's being read. The book might be a mirror she doesn't want to look into. Or perhaps she's using it to hide some flaw in her forehead or maybe the fact that she doesn't have a forehead, since she actually only consists of a segment of a face against a semblance of pillow with a fraction of sheet cutting her off at the chin. Look at the image more closely still and it's almost as if she's been very neatly and precisely mutilated. So much for realism. Woman, bed, bedclothes, book, and cat are all provisional; it's the equivalent of an artist showing you his hand: here are the elements, now see how you can put them together.

It's probably safe to say that the Barnets most people will be moved by are the five on the central wall and the six abstract/non-abstract works juxtaposed on the wall to your left as you enter the main gallery. For this reviewer, pictures like Circe II, Introspection, The Bannister, and Way to the Sea demand elemental, even downright simplistic language. Stand before them and you tell yourself, "Okay, no gushing, this is a serious venue." You may even look over your shoulder to some imagined higher authority raising its enlightened eyebrows and cautioning you to consider that these pictures may be perhaps a bit too close to, well, glorified storybook illustrations, old chap. Decorations. Think Arts and Crafts, Mission, Stickley, and that other Will from the turn of the century, master illustrator and designer Will Bradley, not to mention Aubrey Beardsley. Never mind, you tell the higher authority. If this is "decoration," it's decorative art taken to the highest power. You really like it. It speaks to you. You could live with it. With works as clear and expressive of mood and method as these, it's as simple as responding to music, whether it's a melody line by the Beatles or a Schubert song or a solo by Lester Young.

You have only until February 4 to experience this unique and memorable union of two artists. The exhibit is free and open to the public weekdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., weekends by appointment. The Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries are on the first floor of the Civic Square Building at 33 Livingston Avenue in New Brunswick. And the spirit of Bob Blackburn's famous Printmaking Workshop is alive and well on the second floor of the same building in the Rutgers Center for Innovative Print and Paper.