|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 28

|

|

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 28

|

|

Wednesday, July 9, 2008

|

|

In Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano there’s a passage devoted to the Consul’s library, which includes, among other quaint and curious volumes, Dogme et Ritual de la Haute Magic, Serpent and Shiva Worship in Central America, “numerous cabbalistic and alchemical books,” Gogol, the Mahabharata, Blake, Tolstoy, the Upanishads, Bishop Berkeley, Duns Scotus, Spinoza, Shakespeare, All Quiet On the Western Front, the Rig Veda — and Peter Rabbit.

“Everything is to be found in Peter Rabbit,” the Consul liked to say.

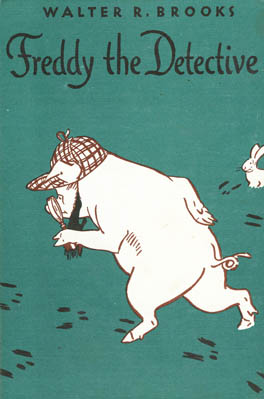

What about Freddy the Pig then? I’ve always considered Walter R. Brooks’s Freddy the Detective the first “real book” I ever encountered. Of course the stakes are not as high, nor as life-and-death. Instead of Mr. McGregor, who baked Peter’s father in a pie, you have Mr. and Mrs. Bean, who treat their animals with the utmost kindness and respect. True, there’s a widow rabbit, Mrs. Winnick, who has been providing for her large family “ever since the loss of her husband” (perhaps Mr. Winnick strayed into the wrong garden). There’s also a trial concerning the alleged murder (and eating) of a crow; two rather hapless human beings who rob a bank; and a fiendishly clever rat named Simon, who faked the business with the crow in order to frame his mortal enemy. What I found in the Freddy books was a well-crafted narrative, a humorous, sympathetic sensibility, a pig who read books and solved mysteries, and, above all, Simon’s nemesis, a roguish cat named Jinx. For Jinx alone I will always be grateful to Walter R. Brooks, who died 50 years ago, August 17, 1958.

The Sublime Jinx

My only quibble with Adam Hochschild’s excellent 1994 New York Times Book Review article (“That Paragon of Porkers: Remembering Freddy the Pig”), which can be found in the online edition, is his failure to mention the most complex, compelling, and charismatic character in the series. Jinx is Huck Finn to Freddy’s Tom Sawyer, Neal Cassady to his Jack Kerouac; he’s Holden Caulfield, Nick Adams, Ishamel, Mercutio, Hamlet, Harpo and Groucho, all wrapped up in one feisty black cat. He’s also the epitome of the cat the jazz world adopted as the essence of crazy and cool, as well as having qualities in common with some very special, unforgettably personable cats that I’ve known.

Some may suggest that in Freddy the Detective, Jinx is merely the Watson to Freddy’s Sherlock Holmes. After all, Jinx didn’t read Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Freddy did; that’s where he got the inspiration. But there’s a moment early in the first investigation when Jinx sneaks on the scene and happens to rub up against Freddy, causing him to jump “violently and let out a startled squeal,” at which the cat whispers, “Shut up, you idiot. It’s only me.” Did Watson ever tell Holmes to shut up, let alone call him an idiot?

Freddy’s got a study with books, all neatly kept in a corner of the pigpen, and he lends them out to the other animals, an activity that must have warmed the heart of many a librarian over the years. He’s also a bit full of himself at times. When he boasts that “there isn’t a pig in the country has a finer library or a wider knowledge,” Jinx “rudely interrupts” and tells him “cut out the hot air.” When the ever-expansive cat makes a point, he gives Freddy “a joyous whack on the back” and goes, “Whamo!”

While Freddy has channeled some of Sherlock Holmes’s ingenuity, he lacks the master detective’s forcefulness. That’s where “good-natured but fierce” Jinx comes in: “a brave and stalwart cat and a fierce fighter.” It’s Jinx who divulges the news that the toy train belonging to the Beans’ adopted son is missing, Jinx who tells Freddy “There’s a job for a detective on this farm right now,” Jinx who snarls, “I’d like to get my claws on the one who took it.” In fact, Freddy’s first appearance is subordinate to his friend. Alice and Emma (the ducks that a real-life Jinx would have attacked on sight) are all aflutter, having been given the shock of their lives by a scary creature with a long white nose. Like a knight in service to two damsels in distress, Jinx springs into action: “There was a commotion among the leaves, a snarl, a shrill squeal of fright, and out ino the open dashed Freddy with Jinx on his back. The cat was cuffing the pig soundly about the head.” Freddy, as it turns out, had been practicing the fine art of “shadowing” on Alice and Emma.

It isn’t merely the freewheeling fighter in Jinx that makes him a hero. He’s the realist to Freddy’s dreamer. Again, as the pig natters on about all the mysteries on the farm and says, “I’ll solve ‘em all. Maybe I can write them up in a book …. And this’ll be the first one, Freddy’s first case.” To which Jinx adds: “If you find the train.” “Oh dear,” says Freddy. “I like you, Jinx, but why do you always have to say things like that. Of course I’ll find it.” Jinx’s grinning reply: “Sure you will, old pig …. Because I’m going to help you.”

You can imagine how refreshing this sassy character would have seemed to someone who once devoured the adventures of those comparative dullards Frank and Joe Hardy and their fat sidekick, Chet. Whenever Jinx is offstage for more than a few pages, Brooks does his best to jazz up the narrative with Freddy searching for missing rabbits and being chased by a real-life robber with a real gun, but the story lags. When Jinx returns to the scene, the action picks up, since he’s the only animal who votes against the idea of having a jail (“Let me get a hold of those rats and you won’t need any jail to put ‘em in”). Then, when Charles the rooster, the consummate windbag, attempts a flowery speech, Jinx “who was always thoroughly exasperated by Charles’s long-windedness,” calls him “a silly rooster” and puts a shiver through him by mentioning the impending wrath of his wife, Henrietta, who pulls his tail feathers whenever she catches him making a spectacle of himself. Later, after Charles has been chosen to be the judge and is making another speech, Jinx does it again by calling out “Hey, Charlie! Henrietta wants you” and urging his accomplices to pelt the rooster with tomatoes.

Although he’s absent from the narrative during the episode where Freddy puts on a Holmesian disguise and joins the robbers as a means of capturing them, Jinx figures prominently in the denouement, a trial scene in which he is accused of killing and eating the aforementioned crow. Freddy mounts a brilliant defense while proving that Jinx has been framed by Simon and his gang. Even though Freddy rightly comes off as the hero, it’s the cat you like as he sits down beside Simon, who immediately bares his teeth. “But Jinx, who was a good-natured cat and couldn’t bear a grudge for very long, even when he had such good reason for it as he now had, merely winked at the rat. ‘Be yourself, Simon,’ he said.”

What a thing to say to your enemy! What a character is this cat! It’s as if Jean Valjean looked at his lifelong nemesis at the end of Les Miserables and said, “Be yourself, Javert.”

A remarkable fellow! A few pages later he’s thinking in metaphors. As he and Freddy the detective’s bovine assistant Mrs. Wiggins see the moon come up over the duck pond, “the water rippled white in the moonlight — just the color, Jinx thought, of fresh cream.”

Two for the Road

The book ends beautifully. The Chaplinesque image of Jinx and Freddy on the “open road” is guaranteed to stoke the wanderlust in the soul of ten-year-old readers on long misty morning schoolbus rides. Mrs. Wiggins watches the two friends go off down the road together. “Long after they had disappeared, the sound of their singing floated back to her through the clear night air.”

“We want a vacation from sin and sensation,” they sing. “We don’t want to work all the time.” So, “it’s out of the gate and down the road/Without stopping to say good-bye,/For adventure waits over every hill,/Where the road runs up to the sky.”

Come to think of it, maybe everything is to be found in Freddy the Pig. Overlook Press has reprinted the entire 26-volume series with the original covers and the Kurt Wiese illustrations at $23.95 a volume.