| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

Two Stars Born to Run Sing of Asbury Park

Stuart Mitchner

Contrary to rumor, Asbury Park is neither dead nor dying. What with regular events at the Paramount Theater and convention hall and a July 4 parade celebrating "Tilly," the giant smiling face that used to greet visitors to Palace Amusements, Bruce Springsteen's "city of ruins" ("the boarded up windows/the empty streets") appears to be undergoing a genuine revival. This renaissance is happening even in the face of numbers recently reported in the New York Times: 36.1 percent of Asbury Park's residents live below the poverty level; its unemployment rate is more than three times the state average; and the crime rate is double the rate of any other municipality in Monmouth County.

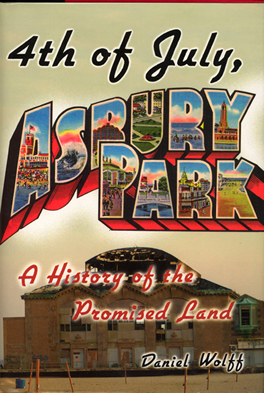

Two other signs of life have surfaced this summer in the form of two very different books – Helen-Chantal Pike's Asbury Park's Glory Days: The Story of an American Resort (Rutgers $29.95) and Daniel Wolff's 4th of July, Asbury Park: A History of the Promised Land (Bloomsbury $24.95). Pike's is one of those diverting, lavishly illustrated compendiums of anecdotes and information that can best be enjoyed through random delvings, while Wolff's meditation on Asbury Park, which takes its title from the first Springsteen song to make the charts, should be read straight through from the beginning. Wolff's book has depth and narrative force. Pike offers a melange of images and personal accounts of the place that could serve as a complement to the other book's more ambitious and imaginative approach. Readers of 4th of July, Asbury Park will probably find themselves wishing for photographs like the ones included in Asbury Park's Glory Days. But those who want a full-scale understanding of an event often blamed for the resort's downward spiral in the 1980s and 1990s need to read Wolff's fascinating account of the race riot that began on the west side of town on July 4, 1970. Whatever you may think of either book, the obvious hero of the Asbury Park story is Bruce Springsteen, who is still giving tangible support and inspiration to the revival of the city that has been so closely identified with the character of his songs. He not only put the place on the map, he made it a site in the imagination of his listeners. People who have lived in Springsteen's songs come to where "the amusement park rises bold and stark" to visit the source, even if Pinball Way or Madame Marie are long gone. When the Boss sets concert crowds rocking and roaring like an evangelical life force rousing the congregation, you can almost believe he has the power to bring it all back again, to make the revival as real as his music. While it may be metaphorically accurate to suggest, as Daniel Wolff does in his preface, that the place never existed, an unmanifested "promised land," it definitely exists in Springsteen's music; it's right there on the cover of his first LP, Welcome to Asbury Park, N.J., in all its gaudy postcard glory.

But Springsteen is not the only heroic creative force in the saga of Asbury Park. There was another star on the scene during the original glory days, another New Jersey native born to run, who lived and went to school in Asbury Park and later covered the resort town for the New York Tribune. While it's true that show-stopping rockers were not to be found back in 1893, Stephen Crane was the literary equivalent of one, a young visionary with a fierce lyric sense and a wholly unique style, his insights edged with irony, his imagery inimitable. If rock equals the life force, as it does with Springsteen, Crane rocked as a journalist, rocked as a novelist, rocked as a short story writer and poet. And died at 28 in a foreign land.

If you know something of Crane's life, you'll understand that it's not all that far-fetched to think that if he'd been born 70 years later he might have felt the call to compose and perform rock concepts and lyrics more seductive than the call to write novels or stories or poems. 4th of July, Asbury Park devotes one of its nine chapters to Crane and makes the obvious connection between the composer of "Born to Run" and the author of The Red Badge of Courage, "a tramp in the sense Springsteen would use the word a century later: an outcast, a renegade, 'tramps like us.'" When Crane describes an American Day parade of workingmen (the Junior Order of United American Mechanics) in Asbury Park, he sees them, in Wolff's words, the way Springsteen would, as "confused, very human heroes": "Almost a century later, Bruce Springsteen would write the music that fit this scene: the heavy dragging beat of his song 'Factory.'"

Stephen Crane's version of "Born to Run" is an Asbury Park story called "The Pace of Youth," in which a boy who works on "Stimson's Mammoth Merry-Go-Round" conducts a silent romance with Stimson's daughter, their love enhanced by the subtle signals and innuendo forced on them because they were so often under the father's suspicious eye: "They were the victims of the dread angel of affectionate speculation that forces the brain endlessly on roads that lead nowhere." In the end, however, the road leads to a rendezvous on the beach and then their escape, with the father in pursuit, his surrender to the pace of youth expressed with a fervor close to that expressed in Springsteen's most famous song as the father comprehends "the power of their young blood, the power to fly strongly into the future and feel and hope again." After quoting from the same passage, Wolff captures the essence of his theme, and Springsteen's song, as he cites Crane's reference to the road vanishing "far away in a point with a suggestion of intolerable length" and then goes on, in his own words: "As if that flashing, fleeting, careening song was somehow always in the future. As if being born to run was both a blessing and a curse. As if Asbury Park were forever."

It's a tribute to Crane's genius that he brings the essence of Asbury Park in its glory more hauntingly to life in this story than anyone else has done, even including Springsteen; the evidence is in his descriptions of the carousel, the beach at night, and the lovers' silent courtship done in a style evoking merry-go-round motion: "They fell and soared, and soared and fell in this manner until they knew that to live without each other would be a wandering in deserts."

Not that Crane's vision of Asbury Park is wholly romantic. Daniel Wolff makes that clear. At one point during his account of the July 1970 race riot, I found myself imagining Crane looking over Springsteen's shoulder: "At the time ... Springsteen was living in a surfboard factory out on the edge of town. When he heard about the riots, he climbed a nearby water tower... From the top of the tower, looking out across Route 35 toward the ocean," he "felt as if he were watching his whole city go up in flames."

Springsteen and Crane both figure in Asbury Park's ongoing renaissance. The house at 508 Fourth Avenue that the Crane family moved into in June of 1883 when Stephen was 11 is still there, with the entire first floor and four public rooms on the second floor serving as a museum dedicated to Stephen Crane. According to the museum website, "the generous donation given by Mr. Bruce Springsteen and friends has been of enormous help in making it possible for recitals, lectures, and poetry readings to take place there."

For now, Mr. Bruce Springsteen's "4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)" has the last word: "Sandy, the aurora is risin' behind us/The pier lights our carnival life forever."