|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 29

|

|

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

|

|

“But there are remises or storage places where you may leave or store certain things … and this book contains material from the remises of my memory and of my heart. Even if the one has been tampered with and the other does not exist.”— Ernest Hemingway, April 1961

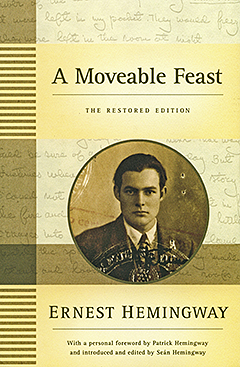

According to Patrick Hemingway’s foreword to A Moveable Feast: The Restored Edition (Scribner $25), the passage quoted above is the “last bit of professional writing” by his father and, as such, constitutes the book’s “true foreword.” Hemingway’s only living son, Patrick suggests that his father’s words about memory being “tampered with” refer to the effects of electric shock therapy (EST). No attempt is made to explain the other half of the memory/heart dynamic, though the implication is that EST destroyed the heart when it attacked the memory. There’s nothing you can say to such a bleak and brutal statement except that it makes sense when you know that Ernest Hemingway, who had tried twice to kill himself earlier that month, would succeed three months later.

Patrick Hemingway is right about the appropriateness of that grim “foreword” only if you agree that the author’s failure to add a final chapter deprives the book of its integrity, leaving a never-to-be-completed posthumous act of remembrance that was “tampered with” 40-plus years ago by Hemingway’s widow, Mary, and an editor at Scribners named Harry Brague, and now by Seán Hemingway, the author’s grandson, who has edited the oddly named “restored” version published on July 12. It’s a Jamesian situation if there ever was one. The 1964 edition took some liberties that the 2009 edition is correcting, except that in the process the editing has further compromised, to quote the jacket copy, “one of the great writer’s most enduring works” by restoring sketches the author rejected (and for good reason). Worse yet, the jacket copy claims that the book is being published “for the first time as Ernest Hemingway intended.”

Looking for the Heart

Ernest Hemingway was born 110 years ago yesterday, July 21. Once you get past the lit-pop-culture legend of the big-game-hunting, deep-sea fishing bullfight aficionado Papa Hemingway, there will always be the young American in Paris sitting at a cafe table writing “The Big Two-Hearted River.” And once you get past the fact that the work he called his Paris book is a posthumous entity with a title not of his own choosing, there will always be something called A Moveable Feast with passages full of the love of art and life and Paris. Never mind trying to match the stereotype of the macho celebrity with the artist practicing his craft and writing about it as feelingly and forcefully as Hemingway does in this book. And never mind that Seán Hemingway is spinning the story so that Hemingway’s second wife, Pauline, Seán’s grandmother and Patrick’s mother, gets her due. “The true gen,” as the author might put it, is that this Jeckyll and Hyde mix of sentiment and malice, spite and insight, is now and will always be one of the great literary memoirs.

“It Gives Me the Horrors!”

As Hemingway states many times over in the “Fragments” section that concludes the new edition, the book’s “heroine” is Hadley, his first wife. His love letter to Paris is also a love letter to her. The problem, according to the April 16, 1961 unsent missive to his publisher cited in the “restored” edition’s introduction, is that he’s “unable to finish the book as he had hoped” and has suggested “publishing it without a final chapter.”

No wonder, since the subject of a final chapter would necessarily involve coming to terms with the end of the idyll and the marriage, a “big, two-hearted” Paris Paradise Lost. And in order to explain the end of a relationship so warmly evoked (enough so that you feel the almost-sixty-year-old Hemingway falling in love with Hadley all over again), he has to put his second wife, Pauline, in the role of a rich temptress, while making the Satan responsible for the loss of paradise the “Pilot Fish and The Rich,” a title he imagines giving to the story he can’t fit into his and Hadley’s Paris. In “Fragments,” he actually imagines a sequel, “the second part of Paris,” which “was wonderful although it started tragically enough. That part, the part with Pauline I have not eliminated but have saved for the start of another book. It could be a good book because it tells many things that no one knows or can ever know and it has love, remorse, contrition, and unbelievable happiness and final sorrow.”

In the 1964 edition of A Moveable Feast, the concluding chapter added by the editors (“There Is Never Any End to Paris”) is reasonably true to the turn Hemingway knew the story would have to take for it to make sense as literature. The denouement begins with a reference to “new people [who] came deep into our lives and nothing was ever the same again.” What follows is a series of paragraphs in which Hemingway vents on the subject, as in the passage about “the good, the attractive, the charming, the soon-beloved [Pauline], the generous, the understanding rich … who, when they have passed and taken the nourishment they needed, leave everything deader than the roots of any grass Attila’s horses’ hooves have ever scoured.”

The next paragraph keeps it up. “The rich came led by the pilot fish.” The “rich” in question, according to Linda Patterson Miller’s Letters From the Lost Generation (Rutgers University Press 1991), are Gerald and Sara Murphy, and the pilot fish, who “was our friend of course,” is John Dos Passos. Hemingway is at his bitter best in the 1964 edition, writing, “In those days I trusted the pilot fish as I would trust the Corrected Hydrographic Office Sailing Directions for the Mediterranean, say, or the tables in Brown’s Nautical Almanac.” In the “restored” edition, however, the same paragraph begins: “It gives me the horrors now to remember it.”

I added the italics to emphasize the way that small suspect sentence jumped out at me, as it would surely do to anyone alert to the intensity of the surrounding prose. It’s hard to imagine a stylist as exacting as Hemingway allowing that lame, pedestrian phrase to surface at such a critical moment. He’s writing what he knows will be the final chapter, after all, which means taking on the thorny task of accounting for his betrayal of Hadley, the heroine of his Paradise Lost. Imagine “The Killers” ending with Nick Adams saying, about the thought of the Swede waiting for death, “It gives me the horrors” instead of “It’s too damned awful.”

“Bonus Tracks”

While the “restored” edition of A Moveable Feast offers some significant contributions, including several pages of fascinating manuscript facsimiles, the new material gathered under the heading “Additional Paris Sketches” makes you thankful that the editors of the 1964 edition generally honored Hemingway’s intentions. In almost every instance, it’s all too clear why he wanted the “additional” sketches omitted. As Seán Hemingway’s introduction points out, Mary Hemingway had already violated the text by changing the order of the chapters, adding sentences her husband had deleted (among them a crack about Scott Fitzgerald), and imposing an entire chapter (“Birth of a New School”) that the author had marked to be left out, probably because it showed him at his nastiest (his victim is Harold Loeb, the model for Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises “who was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton”). That Hemingway could be nasty, petty, and self-indulgent, in his personal life and in his writing, is common knowledge by now, and it’s moving evidence of the value he placed on this book that he knew when he was going over the top and was usually able to balance his score-settling with his art.

The rejected sketches and fragments included in this 2009 edition remind me of the bonus tracks and special features that have become standard practice in the age of CDs and DVDs. Whatever their value as informative, amusing curiosities, it’s not enough to justify the claim that these additions represent a legitimate restoration. In “Secret Pleasures,” a sketch destined to get gossipy book-chat attention, the conversation with Hadley about their matching haircuts is unintentionally funny. The same thing happens in “The Education of Mr. Bumby.” While the references to the Hemingways’ infant son have a charm that helps dilute the vitriolic aspects of the original Feast, in the rejected (now restored) sketch, the same self-indulgent duet is performed, this time with Bumby. Besides sounding off-puttingly smug, Hemingway uses his child to once again stick it to “poor Mr. Fitzgerald.” The author of The Great Gatsby is savaged even more openly in the rejected, now restored, sketch “Scott and His Parisian Chauffeur,” which might amuse Princeton readers if only because of its local references (the aftermath of a Princeton football game in 1928); to include it in the original Feast, where Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald are already sufficiently and devastatingly portrayed, would have been overkill.

That an embattled Ernest Hemingway was strong enough to resist the lesser angels of his nature at a time when he could see the “end of something” looming is a tribute to stamina and craftsmanship sustained against formidable odds. Surely we owe him the right to have it his way as long as we can look past the “tampered with” memory to the young American in Paris sitting at a cafe table writing “The Big Two-Hearted River.”

Note: Hemingway’s great friend A.E. Hotchner’s well-intentioned op-ed piece in Monday’s New York Times (“Don’t Touch ‘A Moveable Feast’”) suggests that the new book “relegated” 10 chapters from the original 1964 edition “to an appendix.” As I’ve pointed out, these chapters, with one exception that was itself taking a misguided editorial liberty, were never part of the book Hotchner is defending.