|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 23

|

|

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 23

|

|

Wednesday, June 4, 2008

|

|

|

“There was a redemptive element in the blackness, ultimate compassion for the suffering of others, and a swath of pure beauty and mystical awe that cut right through the heart of the work.”

—Lester Bangs on Astral Weeks

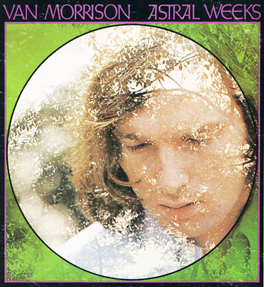

This is an anniversary year both for Johnny Depp, who turns 45 next Monday, and for the album that changed his life, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, which was recorded 40 years ago this fall. Though he came of age a decade later, Depp absorbed the “compassion,” “beauty,” and “mystical awe” Lester Bangs heard in this music created in the heart of the 1960s, and it’s the spirit of that decade, enriched by the influx of forces from the 1950s like Jack Kerouac and James Dean, that shaped and expanded his character as a performer. Johnny Depp is an actor capable of being a genre unto himself, a possibility Murray Pomerance raises in his book Johnny Depp Starts Here (Rutgers 2005). What Depp discovered in the brave new world of Astral Weeks helped him to become, to use Pomerance’s words, an actor “whose selection of roles, whose infusion into the roles he plays, whose depth of commitment to his performance, whose subtlety of expression, whose range of athleticism and grace, whose physical plasticity and immense vocal range, contribute in sum to a performance style that is at once surprising, brilliant, unparalleled, unrepeated, and unrepeatable.”

That description, including, especially, the chorus of superlatives at the end, can also be applied to what happens in Astral Weeks. Though Pomerance covers a dizzying assortment of influences and associations during his expedition into the land of Depp, he begins his book with reference to the Moment of Truth that set up all that followed. Recalling the visitation in the July 8, 1999 Rolling Stone (“The Night I Met Allen Ginsberg”), Depp pictures himself as a clueless 13-year-old daydreaming about girls and listening to a Peter Frampton album when his older brother snatched it off the turntable, “grabbed a record from his own collection” and put it on. Affronted by this fraternal presumption, Depp was prepared to dismiss the music (“They’re not even plugged in! Those guitars aren’t electric!”); all he heard at first was “a guitar, fretless stand-up bass, flutes and some Creep pining away about venturing ‘in the slipstream between the viaduct of your dreams.’” But then the words “began to to hit home; they didn’t play that kind of stuff on the radio, and as the melody of the song settled in, I was starting to get kind of used to it.” A massive understatement. No more songs about “summer breezes and afternoon delights.” A new life had begun: “I needed space to be filled!!! Filled with sound … and words … words that meant something … sounds that meant something!” He describes it as being his “ascension (or descension) into the mysteries of all things considered Outside.”

If you’ve seen or heard Van Morrison in one of his self-instigated onstage trances, stopping and starting, with his garbled “starstruck innuendoes” and stammered summonings of what he calls “the inarticulate music of the heart,” you know just how far outside the norm he can venture. Listening to him being interviewed on a Boston “underground” FM station in the summer of 1968, I felt sorry for the person asking the questions. Other rock stars visiting Boston had been relaxed and forthcoming with this hip young DJ. Not Van Morrison. He was stupefyingly difficult, an interviewer’s nightmare. I could barely make sense of a word he said and neither could the DJ. He might have been talking to a Martian, or to a character as wrapped in the mysteries of the Outside as the ones Johnny Depp plays so brilliantly, like the angelic clown in Benny and Joon. Judging from the discomfort betrayed by this usually super cool radio personality, you’d have thought he was interviewing another Depp outsider named Edward Scissorhands. In fact, the only actor who could play Van Morrison and get away with it is our hero, the same performer who stole Hunter Thompson’s soul in the druggy sixties epic, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Speaking of out-there roles, for a start how about Ed Wood in drag, Willy Wonka, Jack Sparrow, Sweeney Todd, and Ichabod Crane?

Intoxication

While you don’t have to be high to appreciate the wonders of Astral Weeks — which can make you high anyway all by itself — it doesn’t hurt to have some sort of assistance to slow you down and open your mind and senses to just how far from ordinary notions of time and space this music is venturing. In its richest moments, multiple themes and tempos come into play at the same time. You’ve got Morrison strumming strong and steady on his acoustic guitar while singing passionate lyrical incantations that follow their own weird, sometimes staggered, sometimes staggering course; you’ve got a gypsy violinist weaving exotic subplots; you’ve got Richard Davis, one of the best jazz bassists of his generation creating hypnotic counterpoint to Morrison’s incantations; you’ve got the Modern Jazz Quartet’s drummer Connie Kay telling his own story “as the leaves fall one by one by one,” and somewhere in the back streets there’s a classical guitar plucking your heartstrings as Jay Berliner puts another storyline into the mix; there’s also a flute evoking “gardens all wet with rain,” and in the song-movie called “Cyprus Avenue” there’s the tolling effect at the end so evocative and haunting, it’s enough to send you looning off to Van Morrison’s Belfast to see “the avenue of trees” for yourself.

What makes the album so special, so hypnotic, so intoxicating, is the harmonious converging of all these different moods and modes, thanks to Lewis Merenstein’s production and to string arrangements by Larry Fallon that surge, charge, and caress, always at their own suggestive pace. When you put Van Morrison’s singing on top of the glorious chaos of that soundscape, what happens is the “unrepeated and unrepeatable” sublime.

In the Studio

Interviewed years later, Richard Davis could offer no cogent explanation for what happened at Century Sound Studios in New York on September 25, October 1, and October 15, 1968. No plan had been given. “No prep, no meeting,” Davis recalled. “He was remote from us, ‘cause he came in and went into a booth …. And that’s where he stayed, isolated in a booth. I don’t think he ever introduced himself to us, nor we to him … he seemed very shy.” Very strange, he probably means. According to Connie Kay, “When I asked him what he wanted me to play, he said to play whatever I felt like playing.”

Davis also pointed to the importance of the time of day, the most productive session having taken place after dusk, from 7 to 10 p.m: “You know how it is at dusk when the day has ended but it hasn’t? …. You’ve just come back from a dinner break, some guys have had a drink or two, it’s this dusky part of the day and everybody’s relaxed … I remember the ambiance of that time of day was all through everything we played.” As for the dynamic of a situation where the leader is literally outside, “away from it all,” Davis claimed that the musicians actually didn’t pay all that much attention to the lyrics. “We listened to him because you have to play along with the singer, but mostly we were playing with each other. We were into what we were doing and he was into what he was doing,” and instead of falling into chaos, everything fell into place.

“To love the love”

Without making claims for any direct connection between phrases and motifs in Astral Weeks and Johnny Depp’s style as an actor, it’s safe to say that he absorbed some indispensable lessons from the dramatic ways Morrison uses and benignly abuses language, whether he’s stuttering (“my tongue gets t-t-tied”) or riffing (“mym-my-my sweet thing”) or making word-magic into music, most movingly in “Madame George.” When he sings “Dry your eye for Madame George,” who is about to be abandoned and possibly busted, he makes an echo of it, “youreye, youreye, youreye,” which follows what he does with “glove” — “And as you’re about to leave/ She jumps up and says, ‘Hey love, you forgot your gloves,’” inspiring the movingly sung play on “love” and “glove”: “And the love that loves that loves to love the love to love the love the glove.”

Whether you’re an actor or a writer or anyone creating anything, when Morrison bares the heart of the language that way, improvising on the spot, it’s evidence of the daring aesthetic displacements of the Outside, like those words 13-year-old Johnny Depp imagined filling “that space with sound … and words … words that meant something … sounds that meant something!”

Anyone curious to learn more about the creation of Astral Weeks should check out the strong, well-documented entry on Wikipedia, which is where some of my information, including the quotes from Richard Davis and Connie Kay, came from. The album is widely available on CD, which, like DVDs of most of Johnny Depp’s films, can be found at the Princeton Public Library.