|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 23

|

|

Wednesday, June 6, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 23

|

|

Wednesday, June 6, 2007

|

|

Forty years ago today ….

It was the best of times and the best of times.

The first week of June 1967 on radios across land and sea, “the lovely audience” in the makebelieve Music Hall created by the Beatles heard the album that was a legend before anyone played it. Whether or not it was their best (I still prefer Revolver), the record lived up to the legend. It was, simply, amazing. And it was everywhere. The day it came out you’d go to a gas station and the guy filling the tank would ask, “Have you heard it yet?” Somebody else you didn’t know would say, out of nowhere, “They’ve done it again!” No need to specify “it” or “they” — such were the dimensions of the event called Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

It was a heady feeling, to know you were sharing the same excitement, absorbing the same music, with millions of other people, all over the world. At that moment in time, whatever you call the emotive force — joy, love, wonder — the Beatles were the creative common denominator. They reached and enriched more of us than anyone or anything else.

Something comparable had already been accomplished three years before with the movie, A Hard Day’s Night, which I saw numerous times, sometimes bringing people who “didn’t get” the Beatles. When it was over, they’d come out smiling, high and happy, so in love with the movie and the music that they wanted to sit through the whole thing again, which we sometimes did. In August 1964, less than a year after the killing of John Kennedy, we were hungry for joy and the Beatles brought it. And kept bringing it as the music got better and better.

Looking back for us, that great poobah the media punches in the easy slogan, “The Summer of Love,” which the script says was launched by the Beatles. In fact, the same week Sgt. Pepper was released, the cheesiest take ever on the happy hippie summer, Scott Mackenzie’s “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” entered the Top Ten and eventually made it to Number 4 on the singles charts. That maudlin, generally derided ballad played a major part in propagating the media’s catch phrase. As for Sgt. Pepper, although there were no conventional love songs, George Harrison’s “Within You, Without You” celebrated the love “we could all share,” a love that could “save the world,” and no doubt Harrison’s walk through Haight-Ashbury that July helped put the “summer of love” on the map.

Once the general excitement accompanying the album’s arrival had died down, two songs seemed to receive the most attention, “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” and the last track, “A Day in the Life,” which isn’t a song so much as a song within an event within the event of the album. Everyone was talking about the psychedelic magic of “Lucy” and the prodigious crescendo of sound that explodes midway through and at the conclusion of “A Day in the Life.” Instead of straight love songs like McCartney’s brilliant “For No One” on Revolver, you had “Getting Better” (“I used to be cruel to my woman/I beat her”) and “Lovely Rita” (“When it gets dark I tow your heart away”) and Ringo answering the question “What do you see when you turn out the light?” with “I can’t tell you but I know it’s mine.”

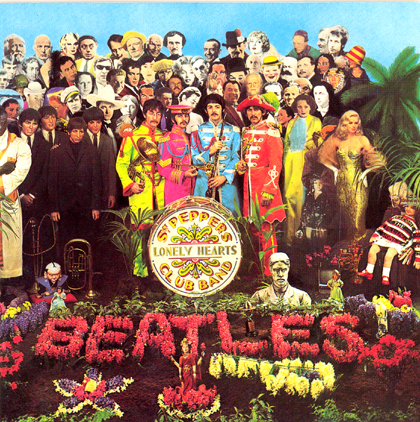

One reason it’s hard to rank Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as high musically as Revolver or Rubber Soul or the second side of Abbey Road may be that the concept very nearly outweighs the music. That massive noise made by a 41-piece orchestra in “A Day in the Life” (“McCartney told them to play as out of tune and out of time as possible”) was commissioned but not performed by the Beatles, and even though it still stands as a prophetic analogy for any momentous event, from 9/11 to nuclear apocalypse (Lennon asked producer George Martin “for a sound like the end of the world”), it isn’t in itself worth a single song like “Rain” or “Here Comes the Sun” or any number of others. Another example of the way the event detracted from the music was the concept of the cover, which showed the group both as the mythical band of the title and as Madame Tussaud dummies of themselves surrounded by the likes of Wittgenstein, Lawrence of Arabia, Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, Marlon Brando, Marilyn Monroe, Dylan Thomas, and Edgar Allan Poe. There were even contests nationwide where free copies of the album went to contestants who could identify the largest number of faces in the crowd. As brilliant as it was, the idea of having the Fab Four pose among a wildly mixed group of celebrities, living and dead, wasn’t music, and the art of the cover, like the crafting of the big sound, was performed by someone else.

However, having just listened to my ancient vinyl copy of Sgt. Pepper, I realize the obvious: that the distractions of the concept are history; what matters is that the music’s still fabulously alive. If you listen to it again, whether on vinyl or tape or CD or MP3 or headphones, you’ll hear the beauty of the arrangements and the singing; the way John Lennon’s voice is used to balance the sentiment in “She’s Leaving Home”; the way George Harrison’s searing, stinging guitar licks ignite the band, especially in the theme song and its reprise; and then there’s Paul McCartney’s almost otherworldly-great bass-playing time and again living out that old line, “tripping the light fantastic.” As for the ever-underrated Ringo Starr, he’s almost as inventive a drummer as McCartney is a bassist.

Love to the World

Later that month, on June 25, the Beatles sent the most potent imaginable love message via satellite to 24 countries and an estimated 400 million people on Our World, the first-ever live worldwide television broadcast, performing a song John Lennon wrote especially for the occasion. He had been advised by the BBC to “keep it simple so viewers across the globe will understand.” The group had less than ten days to come up with something that would match the dimensions of the event, which “All You Need Is Love” did and then some. It was an anthem not just to love but to hope and perseverance, creation and knowledge. The quality of the moment (six minutes to be exact) was in the colorful audience that included Mick Jagger and Eric Clapton singing along to the chorus and parading about waving Love placards in different languages, and in the way the camera zoomed in on the control board and cameoed the cellists, the violinists, the trombonists, and the Penny Lane trumpets. But what moved everything to a higher level were the close-up side-views of John Lennon singing (“Nothing you can make that can’t be made/No one you can save that can’t be saved”). Lennon’s voice can send chills up your spine, especially when he merges opposite emotions; he can be simultaneously wistful and rawly passionate, angry and aching. That day, with people on every continent listening, he sang as if he really believed he and his band could save the world for love and peace.

You have to think something special was in the air 40 years ago. The musical excitement wasn’t all Beatles in the summer of 1967. Extraordinary songs seemed to be playing every time you turned on the radio, AM or FM: songs like “A Whiter Shade of Pale” by Procul Harum with its out-there lyrics and Gary Brooker’s unforgettable singing, and “Light My Fire” by the Doors. Wonderfully quirky songs like “Happy Jack” by the Who were making the Top 40, and earlier in 1967 one of the great songs of the time, Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” went to number 7, its quiet ominous urgency presaging the riots and assassinations that lay ahead, so much so that you’d think it had to have come out in the summer of 1968 rather than the spring of 1967.

I haven’t even mentioned what the Beatles did before and after Sgt. Pepper: releasing a single in February the likes of which had never been heard on Top 40 radio (“Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields Forever”), and coming up with songs like “Fool on the Hill” and “I am the Walrus” that fall.

Einstein Was There

Princeton’s most renowned resident can actually be found among the crowd on the cover of Sgt. Pepper, though he’s obscured by John Lennon’s shoulder. If you look at unused outtakes from the photo session, you’ll see a middle-aged Albert Einstein in a gray suit looking a bit lost in the crowd. If you doubt that Einstein was on the scene in spirit the day Sgt. Pepper “taught the band to play,” consider the recent Rolling Stone interview with the Beatle who emceed the album. When he was asked what continues to speak to people in the Beatles music, Paul McCartney put it this way: “Life is an energy field, a bunch of molecules. And these particular molecules formed to make these four guys, who then formed this band called the Beatles and did all that work.”

Some of my information about the Sgt. Pepper period came from William J. Dowdling’s handy compendium, Beatlesongs (Fireside 1989) and Mark Lewisohn’s even handier The Beatles Recording Sessions (Harmony 1988). The McCartney interview appeared in the 40th Anniversary issue of Rolling Stone (May 3-17). There’s also an excellent profile of McCartney in this week’s (June 4) issue of the New Yorker.