|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 23

|

|

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

|

|

|

In Allen Ginsberg’s poem “City Lights City,” a flight of fancy from 1994 set in 2025, the streets and landmarks of San Francisco bear the names of literary figures. The Oakland Bay Bridge and Golden Gate have been named for Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder; it’s the Ken Kesey Freeway, not the Bayshore; there’s a Robert Duncan Boulevard with cross-streets named for Diane DiPrima, Henry Miller, and Gregory Corso (the latter being home to the Neal Cassady R.R. Station); Czeslaw Milosz Street signs “shine bright on Van Ness,” a Philip Lamantia Tower “crowns Telegraph Hill,” and on Via Ferlinghetti & Kerouac Alley “young heroes muse.” It’s a Mecca of theosophic shops, where the Greyhound Station is “surrounded by Bookstore Galleries, Publishers Rows, and Artists lofts.”

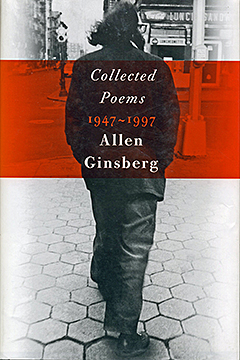

There’s a noticeable jump in time after “City Lights City,” dated April 21, 1994, to the poem dated January 1995 that follows it in Collected Poems 1947-1997 (Harper-Collins 2006). A no less striking jump is in subject matter, from poetical fantasy to the political reality of a nemesis who is still throwing his weight around in the 2009 media circus of cable news. “Newt Gingrich Declares War on ‘McGovernik Counterculture’” unleashes a barrage of questions, beginning “Does that mean war on every boy with more than one earring on the same ear?” and ending with another of Ginsberg’s numerous references to Princeton’s most famous former resident: “Is ecology pro or counter culture? Astronomy determining the Universe’s age & size? Long hair, relativity, is Einstein countercultural?”

The reference to Newt, which, as always, evokes the witches in Macbeth (“Eye of Newt and toe of Frog”), coincides with a recent fantasy of my own, where Ginsberg’s alive and wildly well and with us again, in his May King prime, as the anti-Limbaugh, anti-Rove, anti-Cheney, driving the Right mad with his mantras and harmonium ecstasies. As Limbaugh’s ratings plummet, Cheney is coaxed by his daughter to be a guest on the Ginsberg Show, and before the ex-Vice can further poison the airwaves with his insidious when-they-strike-again paranoia, he and his daughter have joined the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. It may sound unlikely in 2009, but there was a time when Ginsberg seemed capable of such magic, so great was his nerve, his genial gall, thrusting his head into the open jaws of the Beast as he did when he appeared on William F. Buckley’s Firing Line armed with his harmonium and chanting “Hare Krishna.”

Super Poet

You hear about performers who now and then put on a lackluster show, going through the motions. Bob Dylan fans tell me they never know what to expect. Even Sonny Rollins has off-nights. I can’t imagine Ginsberg, who probably holds some sort of world record for the thousands of readings he performed, ever giving any less than his all, no matter how lousy he may have felt or how unlikely the audience. And forget the term “counterculture”: he wasn’t counter anything. He wanted to run the show. He later claimed he was joking when he wrote in “Ego Confession” of wanting “to be known as the most brilliant man in America,” “the secret young wise man … who overthrew the CIA with a single thought,” except that he was serious. When he imagines himself singing a blues that makes rock stars weep or envisions himself as “the spectacle of Poesy triumphant over trickery of the world,” he’s in Faster-Than-A-Speeding-Bullet territory: Super Poet the man of steel from the distant galaxy William Blake who turned back “petrochemical Industries,” “Chopped wood, built forest houses & established farms/distributed monies to poor poets & nourished imaginative genius of the land” and even “climbed mountains to create his mountain.” If you’ve ever read or seen Ginsberg, you know he’s not just kidding around. He wanted to save the world and he wanted his consciousness to be everywhere, the ultimate Open Mind. In a 1992 interview with Alexander Laurence, he’s upfront about it: “A lot of my writing is to attract lovers, like in ‘Personals Ad.’ … the whole body of my work is a big personals ad. That’s a big motivation, to make myself open and candid.” Like New Jersey’s original Super Poet, Walt Whitman. The title and subtitle of Bill Morgan’s recent biograpy says as much, I Celebrate Myself: The Somewhat Private Life of Allen Ginsberg (Viking 2006).

It wasn’t always celebration. From the time he “told all” in Howl, he’s shown the world all sides of himself. The poem follows that rhapsodic “Ego Confession” in his Collected Poems is “Mugging,” wherein Super Poet is set upon by some “young fellows” who trip him up and drag him into an abandoned store and relieve him of 70 dollars and his “old broken wallet.” That’s the Ginsberg dynamic. One minute you’re on the mountain, next thing you know you’re flat on your back chanting “Om Ah H¯um.”

If, like me, you care that today, June 3, is Allen Ginsberg’s birthday (he’d be 83), you’ll find yourself missing the actual living speaking life-force that went by his name more than you do his peers Kerouac and Burroughs because no one else ever kept their sights so relentlessly on the course of the nation and the world. Ginsberg cared. He was “on it” (as they say in the Counter Terrorism Unit on 24). The Beat clown who was mocked in Time in the late 1950s had the media dancing to his tune a decade later. That’s why we could use him today. The Bush years might have been a little more tolerable if we’d had Ginsberg in his prime, writing of 9/11 and Afghanistan and Iraq and chanting us through events like Katrina. Even as a kid, he was clipping newspapers, writing the essential information in his journal, taking the measure of the news, as can be seen in The Book of Martyrdom and Sacrifice: First Journals Poems 1937-1952 (DaCapo 2006) where he also faithfully records the titles of every movie he’s watched (“Saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs — exceedingly good. I sat through the picture three times”); when he fails to provide the specifics (“Celebrated New Year by seeing two movies in succession”), he chides himself in the margin four years later, “Should have put down which.”

Face to Face

You can see Ginsberg up close on YouTube in the BBC2 program Face to Face with Jeremy Isaacs, recorded in January 1995, two years and three months before he died and some months before he appeared in front of an overflow crowd in Princeton. Here he is, patiently and politely doing his quietly earnest best to answer questions that are occasionally patronizing and snidely disingenuous. What distinguishes the 40-minute session is the way it truly focuses on Ginsberg, thanks to the virtual invisibility of the interviewer. You only hear the clipped, veddy BBC-British disembodied voice. “The beard and the hair are trimmed,” the voice observes. “You have a suit and collar and tie. Is the real Allen Ginsberg still in there?” By that he means of course the extravagantly bearded, longhaired wild man, the happy warrior face on a million posters. After pointing out that he’s a Buddhist and therefore believes there’s no real him, just “appearances of self,” Ginsberg goes on to admit “certainly” being a Beat poet, Jewish, American, a “practicing meditator” before identifying himself as “part of the counterculture which is now under attack by neo-conservative theopolitical televangelists.” According to Collected Poems, he wrote “Newt Gingrich Declares War” that same month. And if you google YouTube you can see what else he was up to during his London visit, sitting onstage at the Royal Albert Hall joyfully reciting “The Ballad of the Skeletons” (“Said the Presidential Skeleton/I won’t sign the bill/Said the Speaker skeleton/Yes you will”) while being forcefully accompanied on guitar by Paul McCartney. Gus Van Sant’s video of the “Ballad” is also viewable online.

In Princeton

Although he apparently didn’t write a poem about his last reading on campus, in McCosh in February 1996, the auditorium packed, so that closed-circuit TVs had to be set up, in 1970’s “G.S. [Gary Snyder] Reading Poesy at Princeton,” he imagines Scott Fitzgerald weeping “to see/student faces celestial, longhaired angelic Beings planet-doomed to look thru too many human eyes?/Princeton in Eternity!” The poem that follows, “Friday the Thirteenth,” begins with lines that have an eerie post9/11 resonance: “Blasts rip Newspaper Gray Mannahatta’s mid day Air Spires,/Plane roar over cloud, Sunlight on blue fleece-mist, I travel to die.” Twenty-seven years later in “Things I’ll Not Do (Nostalgias),” his last poem, written when he was dying, most of what he imagines not being able to do is related to travel: never going to Bulgaria or Albania, or Lhasa or back to Benares, or Madras or Calcutta, or Tangier, or “Old opium tribal Afghanistan.”

Two Bookstores

“City Lights” in the poem “City Lights City” refers to Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s bookstore and City Lights Books, whose Pocket Poets Series published Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. The East Coast equivalent of City Lights was “Greenwich Village’s Famous Bookshop,” the Eighth Street, whose owners Ted and Eli Wilentz also had an imprint, Corinth Books, which brought out a volume of Ginsberg’s early poems under the title, Empty Mirror. My own Ginsberg moment occured at the Eighth Street. Just out of college, working on the accounts up on the second floor on a dark winter evening, I hear footsteps on the stairs. It’s Ted Wilentz, the co-owner, my boss, and he’s brought someone to meet me. We shake hands, say a few words, and before I can take it in — bringing Allen Ginsberg to meet me, a young nobody — the footsteps are going back down the stairs again.