|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 25

|

|

Wednesday, June 20, 2007

|

|

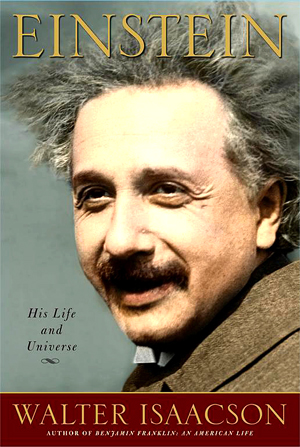

Reading Walter Isaacson’s biography, Einstein: His Life and Universe (Simon & Schuster $32), I couldn’t help imagining a Monty Python parody of the worldwide sensation caused by the Relativity Theory. It would be the ultimate Shaggy Dog story, the apotheosis of all Red Herrings, with an Einstein-type protagonist as a Wizard of Oz creating a smokescreen of inscrutable mathematical evidence (opportunely supplemented by the light-bending effects of an eclipse of the sun) around a planet-altering postulate that no one understands except for a handful of seemingly infallible authorities, who, having been effectively mesmerized by the Wizard (and maybe coached by his agent), proclaim the not-since-Newton greatness of the discovery. Let the media and human nature take care the rest, and shortly thereafter the Wizard is riding down Fifth Avenue in a tickertape parade.

Isaacson provides a nicely articulated examination of Einstein’s work, a sort of high-class Idiot’s Guide to Relativity. While the explanations seem to make sense for a time, idiocy eventually wins out, at least in my case. After an amusement park ride of analogies (a man in an armchair and a woman in a plane flying overhead, Galileo’s ship, a Jet Ski heading into waves at 40 mph, a ray of light sent alongside a railroad track and a woman riding in a very fast train carriage, lightning bolts striking train tracks), it’s a relief to come back to reality in the form of a postcard sent by Einstein after he and his wife celebrated the discovery, “both of us, alas, dead drunk under the table.”

You feel a bit less like an idiot when you learn that only a few physicists truly understood what Einstein had accomplished. It also helps to read the anecdote about Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization and a “brilliant biochemist,” who in 1921 persuaded Einstein to accompany him on a trip to America to help raise funds to create a Hebrew University in Jerusalem. It was Einstein’s first trip to the States, not to mention his first visit to Princeton (“young and fresh,” he thought, like “a pipe unsmoked”), where the University gave him an honorary degree “for voyaging through strange seas of thought.” During the 13 days he was voyaging across the strange Atlantic to America, he tried to explain Relativity to Weizmann, who, when asked upon arrival if he understood the theory, put it this way: “During the crossing, Einstein explained his theory to me every day, and by the time we arrived I was fully convinced that he really understands it.”

Character

Presumably the “dead-drunk-under-the-table” postcard is among the newly released personal letters the jacket copy mentions in heralding Einstein as the first full biography since the new material became available. In lesser works, the “personal” angle is often exploited for the sake of the sort of sensational gossip that dominates television news these days. In this admirable book, however, it establishes character. Isaacson understands that the unique chemistry of the man ultimately transcends the science. He clarifies his priorities early on when introducing Einstein’s first wife “who was known neither for her looks nor her personality.” She had a congenital hip dislocation that caused her to limp and she was “prone to bouts of tuberculosis and despondency.” But she also had “a passion for math and science, a brooding depth, and a beguiling soul.” That Einstein preferred her to the conventionally lovely young woman he was in love with when he met her tells you a lot about his character. The way Isaacson phrases the power of the attraction also tells you a lot about Isaacson and his book: “She would create an emotional field more powerful than that of anyone else in his life. It would alternately attract and repulse him with a force so strong that a mere scientist like himself would never be able to fathom it.”

“A mere scientist!” I felt like cheering when I read that. For all the wonders and monstrosities science has produced, from computers to weapons of mass destruction, it can’t produce an Einstein, who was also a “mere scientist” when attracted and repelled by music, preferring Schubert, with his “superlative ability to express emotion,” to Beethoven (“too personal”); an Einstein whose “heart never bleeds,” whose “apartness” and “personal detachment” were necessary to his “scientific creativity,” and whose eyes would fill with tears during the last scene in Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights.

The Art of Mystery

One of the givens in the field of energy created by international fame is that two such forces as Einstein and Chaplin would inevitably come together, as happened when Einstein was visiting California in 1931. (According to Chaplin’s autobiography, the two men actually first met in 1926.) As Isaacson makes clear, Einstein was a performer in his own right; he did not shy away from the limelight. Writing of the persona of the Princeton Einstein we venerate with anecdotes, photos in shops, and busts in the heart of the Borough, the biographer comes back to the Chaplin connection:

“He was able to make his rumpled-genius image as famous as Chaplin did the little tramp. He was kindly yet aloof, brilliant yet baffled. He floated around with a distracted air and a wry sensibility …. This role he played was not far from the truth, but he enjoyed playing it to the hilt, knowing that it was such a great role.”

As Chaplin and Einstein walked into the theater together at the premiere of City Lights, they were applauded. “They cheer me because they understand me,” Chaplin reportedly said. “They cheer you because no one understands you.”

In the photograph taken on that occasion, both men are in formal attire, but Chaplin out of costume looks like a boyish lightweight next to the longhaired man with the bushy mustache. The Chaplin they were cheering was not the man in the tuxedo but the character he created, who was always much more lovable and accessible than the man. The Einstein they were cheering was the man they saw. You can see the same quality in a photo taken during that California visit, where he’s seen standing with a group of men (most likely members of the Cal Tech faculty) in front of the Mt. Wilson Observatory; the contrast between Einstein and the rather stiff assortment of academics and administrators in period hats and suits reminds me of pictures taken of Indian holy men like Vivekananda and Ramakrishna on their visits to America, where they were sometimes photographed standing next to ordinary mortals in ordinary clothes. As Isaacson writes of Einstein, again in his later, Princeton years: “He came to look even more like a prophet, with his hair getting longer, his eyes a bit sadder and more weary.” The early chapter called “Einstein’s God” suggests that those Hindu seers would have had more sympathy with Einstein’s concept of religion, and his dismissal of a personal god, than the Christian theologians who suspected that “the ghastly apparition of atheism” might be hiding behind Einstein’s “doubt and befogged speculation.” (In fact, Einstein had more contempt for atheists than he did for true believers.) In his book, What I Believe, he writes, “The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of all true art and science.”

Einstein’s susceptibility to the beauty of the mysterious suggests what brought him to the point of tears in the stunning last scene of City Lights. It also suggests that Chaplin’s claim that people understand him oversimplifies his genius, which in its purest form goes beyond comedy into the area of emotional mystery that moved Einstein. The achievement on film of something like the look that passes between the wretched Tramp and the wonder-struck girl who can “see” because of his love stand as Chaplin’s cinematic equivalent to Einstein’s Theory.

Beyond Politics

In Einstein On Politics: His Private Thoughts and Public Stands on Nationalism, Zionism, War, Peace, and the Bomb (Princeton University Press $29.95), David E. Rowe and Robert Schulmann have compiled exactly the book readers of Einstein: His Life and Universe may want to consult during or after reading a biography of the “mere scientist” who held passionate and often outspoken views on the major issues of his time. In fact, “mere politics” isn’t a sufficient phrase for the complex mixture that was Einstein. What it comes down to is expressed by Isaacson himself on the jacket of Einstein On Politics where he writes, “Einstein’s humanism shines through on every page.”

It’s Princeton’s good fortune that some of the most luminous images we have of this humanism were captured here during the last 22 years of Einstein’s life. Isaacson provides an excellent account of the Princeton period (Einstein’s wife called the town “one great park”; it reminded her of England), but nothing he can say tells us as much about the man’s presence here as the endpaper photograph of the lone figure walking homeward on the grounds of the Institute. His back is to us in that picture, as if he were walking into history. It also recalls the emblematic Chaplin vision of the little tramp walking down the road with his cane and his bundle, humanity ever moving on, humbled before the great mystery, a version of what Einstein had in mind when he wrote to his mentally ill son, Eduard: “Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance you must keep moving.” But the biography’s most touching image is found among the photographs inside. Einstein is walking toward us, with Fuld Hall and a bare tree in the background. He’s in a rumpled overcoat with a briefcase under his arms, a knit cap on his head, tufts of his ample white hair poking out on either side. He’s looking careworn and thoughtful, again in Isaacon’s words the “prophet … whose face grew more deeply etched yet somehow more delicate …. He was dreamy, as he was when a child, but also now serene.” And in Einstein’s own words, he appears no “stranger” to “the mysterious,” a man who can still “wonder and stand rapt in awe” — as long, he writes, as the beauty of the mystery “is something that our minds cannot grasp, whose sublimity reaches us only indirectly: this is religiousness. In this sense, and in this sense only, I am a devoutly religious man.”