|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 11

|

|

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 11

|

|

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

|

|

“Art is not pacification. It’s disturbance.”Edward Albee in a 1980 interview

Today is Edward Albee’s eightieth birthday, and if he takes the occasion as seriously as he did in 1958, he’s probably at work on something. According to the authorized chronology accompanying Conversations with Edward Albee (1988), he wrote his first play, The Zoo Story, “as a present to himself on his thirtieth birthday.” Adopted into a wealthy family two weeks after he was born, he was named for his adoptive grandfather, the owner of vaudeville theatres in the Keith-Albee circuit. While The Zoo Story was the first work of his to be produced and gain recognition, he actually wrote his first play when he was 12, which, according to the chronology, would have been around the time he was a student at Lawrenceville School — from which he was expelled. Like Holden Caulfield, he was also expelled from Valley Forge Military Academy. As he tells one interviewer, he “lived” The Catcher in the Rye.

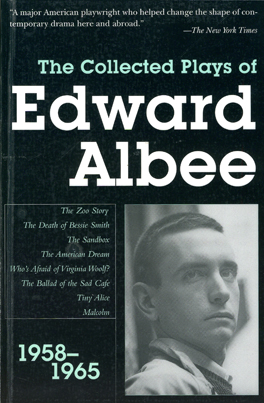

Zoo Story was followed by The Death of Bessie Smith, The Sandbox, and The American Dream, all of which dominated the 1960-1962 Off-Broadway scene ahead of his first full-length play, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which was produced at the Billy Rose Theatre on Broadway in October 1962 and ran for 664 performances. All these plays, along with Tiny Alice (1964) and Albee’s adaptations of two works of fiction (Carson McCullers’s The Ballad of the Sad Cafe and James Purdy’s Malcolm) are included in the first volume of The Collected Plays of Edward Albee (Overlook Duckworth), which came out last year in paperback ($24.95). Three volumes spanning work between 1958 and 2003 have been published so far, and all are available, as is Conversations with Edward Albee, at the Princeton Public Library.

Stage vs. Page

Reading the text of plays without seeing them performed is a bit like reading song lyrics without hearing the music. You need the dimension of performance and all the nuances that accomplished or inspired actors can communicate or discover in the playing. Even so, when you read the brilliantly scary ravings of Jerry in The Zoo Story or George and Martha’s best shots in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the words jump off the page. Of course nothing can match the excitement of seeing and hearing what an inspired cast can do with those words, particularly when the actors are Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor in the film version of Virginia Woolf (1966). Here you see a real-life couple giving the performances of their movie lives as a couple at war and at play, tooth and nail, no holds barred, and obviously enjoying themselves as they tear into one another.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf broke the bounds of the medium; it was not merely a play, it was a phenomenon, an unprecedented theatrical and cultural event. I can’t find the exact phrasing of British critic Kenneth Tynan’s response but it was something like “Why is it that excitement like this always comes from America?” He was writing in the context of England in 1962, two years before the excitement called the Beatles landed in New York, spearheading the British invasion that opened up the sunny side of the sixties.

The arts and entertainment world wasn’t exactly a wasteland in the years just before Virginia Woolf exploded on the scene. You had Lolita, On the Road, Catch-22, the Grove Press edition of Tropic of Cancer, recordings by Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, not to mention the election of John F. Kennedy. But this play about an academic couple at a small New England college (what could be duller to imagine?) gleefully destroying and putting each other back together again sent off shock waves that reached beyond New York three years before the film was released. How was such a thing possible? You could say it was word of mouth, an appropriate phrase given the word-drunk brilliance of George and Martha in full furious flight — but that isn’t enough to explain the way the play reached into every corner of the country. No, there was something else, something tangible: a long-playing original cast album on Columbia of the whole free-for-all, featuring the original actors, Arthur Hill and Uta Hagan as George and Martha, and George Grizzard and Melinda Dillon as their foils and victims, Nick and Honey. Saturday Review critic John Gassner wrote in June 1963 that the record “comes alive as few previously recorded performances of plays have done,” and that the dramatic action is delivered “powerfully without recourse to other theatrical elements.” Based upon hearing rather than seeing the play, Gassner’s observation that it’s “composed of a series musico-dramatic moments” bears out the importance Albee has given to the “equivalent structure in music” to “the form and sound and shape” of his work (“I find that when my plays are going well, they seem to resemble pieces of music”). Albee had classical music in mind, but the furious, slashing George-and-Martha counterpoint could also be compared to a couple of dueling rappers using all the word-weapons in their repertoire.

Around the same time the record came out, the first album by Mike Nichols and Elaine May was in the stores and undoubtedly outselling the more expensive Albee set. But just as people all over the country memorized Nichols and May routines like the one about the adultress and her lover guiltily and tearfully listing the virtues of the betrayed husband (“He’s a saint, he’s a saint!” “He’s the only living saint I know!”), many of the same listeners were going around quoting George and Martha, especially Martha’s opening declaration as she surveys the brilliantly cluttered chaos of their living room: “What a dump!” Taylor gives that “p” the full Bette Davis treatment with great joy. It’s even said that Bette Davis and James Mason were mentioned for the lead roles when the film was cast (imagine Bette Davis doing a faculty wife imitating Bette Davis). “Joy” and “fun” aren’t words you often hear among the references to “shattering drama” and “dramatic fire,” but it’s no stretch to match Albee with Nichols and May. If Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is the best film work Taylor and Burton ever did, it’s probably Mike Nichols’s best work as a director. It was also his debut. And a decade and a half later he and Elaine May were playing George and Martha in New Haven.

Blazing the Way

The movie version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf had a substantive impact on Hollywood, evidence of which can be found on the documentary about the making of the film that comes with the DVD. According to Jack Valenti, who had just taken over as the president of the Motion Picture Association of America, the movie “drove a stake into the heart of censorship.” He also compared it to “a burning arrow” fired “into a haystack.” Suddenly audiences were hearing language that had never been heard on the screen before, even back during the relatively unsupervised and uninhibited pre-Hays Office years. It took some determined diplomatic maneuvering to get Edward Albee’s trailblazer onto the screen virtually intact. The fact that Hollywood wasn’t afraid of Virginia Woolf opened the way for the nudity in Antonioni’s Blow-Up the same year and for everything that has followed, for better or for worse.