| NEWS |

| |

| FEATURES |

| ENTERTAINMENT |

| COLUMNS |

| CONTACT US |

| HOW TO SUBMIT |

| BACK ISSUES |

caption: |

Shakespeare and Company: Portrait of a Bookshop

Main Gallery, Firestone Library

Stuart Mitchner

Short of turning the main gallery at Firestone Library into a replica of Sylvia Beach's Paris bookshop, the curators have arranged "Portraits of the Lost Generation" in a way that effectively suggests the atmosphere of the place and the time: Shakespeare and Company between the wars (1920-1939). The subtitle of the exhibit puts the emphasis on the photographs taken by Man Ray and "other expatriates," but what makes it worth seeing is something more subtle than the quality of the photography. A number of these images have already appeared in various memoirs, histories, and biographies. Some are little more than snapshots and have value mainly because of the subject or the subject's signed inscription. Such is the nature of this illustrated gathering of the writers and artists who frequented the bookshop during those years, however, that the aging of a faded photograph becomes aesthetically pleasing in itself. Man Ray's picture of William Carlos Williams says as much about the presence of the shop over time as it does about the presence of the poet. In the photo Sylvia Beach snapped of Ezra Pound as he stood intently reading, surrounded by books, what comes through is the character of the place and a sense of the owner's proprietary satisfaction at having captured a special customer and a special moment. Because 80-plus-years have dimmed the image, the moment and the man seem to be receding deeper into history even as you look.

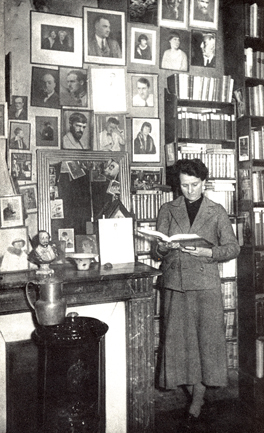

For all the stress on expatriates and the so-called lost generation, Shakespeare presides over the exhibit as he presided over the actual bookshop at 12 Rue l'Odéon, its patron saint, his face on the signboard hanging in front (now hanging on the west wall of the gallery), his name in large letters above the entrance. In her memoir, Shakespeare and Company, Ms. Beach says she picked "my partner Bill" because she felt he was always "well-disposed to my undertaking; and, besides, he was a best seller." The first thing you see as you enter the gallery is a small oak wall cabinet containing the toy soldiers who, in the owner's words, "stood guard over the House of Shakespeare" and, for that purpose, were stationed near the entrance. Here, too, is the small Staffordshireware bust of Shakespeare that occupied Ms. Beach's desk. The same painted figurine (the Bard cloaked in a dark red mantle) appears again in the same display case in the photograph of Ms. Beach and her fellow bookseller, Adrienne Monnier, whose shop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, was also located on the Rue l'Odéon. Some of the photographs on display at Firestone are visible in the background, along with the cozily cluttered, book-laden interior where young Ernest Hemingway browsed and took advantage of Shakespeare and Company's lending library in the days when "there was no money to buy books." In his Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast, he writes of "a warm, cheerful place with a big stove in winter, tables and shelves of books" and "photographs of famous writers both dead and living. The photographs all looked like snapshots and even the dead writers looked as though they had really been alive." Hemingway's laconic observation is no less true of the "dead writers" in this exhibit.

The Princeton Connection

In describing the Rue l'Odéon, Ms. Beach mentions a theatre at the end of the street that reminded her of "Colonial houses in Princeton." In fact, she came to Paris from Princeton, where she grew up. Her father was the minister of the First Presbyterian Church from 1906 to 1923. When she decided to make her dream of a Paris bookshop a reality, she sent the following cable home to her mother: "Opening bookshop in Paris. Please send money." Her mother sent all her savings.

As you move through the remnants of Shake- speare and Com- pany, it begins to seem that the expatriate movement was born in New Jersey. For instance, Man Ray, the surrealist/dadaist painter/photographer featured in the exhibit, came to Paris from Ridgefield, where his name was Emmanuel Radnitsky. The "Bad Boy" of music, composer George Antheil, another self-created Parisian who can be seen here in two Man Ray photos sporting an exotic, almost Beatlesque haircut, grew up in Trenton and emigrated to Paris after showing little aptitude for his father's business, the Friendly Shoestore. Then, of course, there's Princeton's own F. Scott Fitzgerald, who rates more space in the exhibit than any other writer except Gertrude Stein. Also on view is Lawrenceville's Thornton Wilder, and, of course, the aforementioned William Carlos Williams from Rutherford.

Man Ray is quoted as saying "I photograph the things I do not wish to paint, the things which already have an existence." The "things" here are people, most of them writers; examples of his more characteristically inventive work are displayed in the alcoves (he calls some of these "rayographs"). His comment after photographing Gertrude Stein in 1922 indicates that he might have been tempted to take liberties but thought better of it, deciding not to try "fantasy or acrobatics with her physiognomy." In a Ray photograph of Stein that shows her posing for sculptor Jo Davidson, she looks like a football player hunched forward on the bench. Her reaction to Davidson's depiction of her suggests that Ray was wise to avoid improvisation; according to the posted commentary, she said: "That's Gertrude Stein, that's all of Gertrude Stein, that's all of Gertrude Stein there is." Probably the most familiar image of Stein after the Picasso portrait is the photo of her sitting opposite her companion, Alice B. Toklas, in their Rue de Fleurus parlor, a picture taken by Ray's then-assistant Berenice Abbott, who went on to greater things with her brilliant photographic studies of New York City in the thirties.

Several of the most memorable images are by unknown photographers, including the digital reproduction of one from 1925 showing the Fitzgeralds, Scott, Zelda, and daughter Scotty, kicking up their heels in front of a Christmas tree, and one of Ernest Hemingway on the beach, naked except for a makeshift fig leaf.

Purely in terms of quality and composition, Gisèle Freund's may be the best photographs in the exhibit. It is easy to imagine making a painting, or an illustration for a childen's storybook, from her gelatin silver print of the front of Shakespeare and Company that shows Adrienne Monnier hunched over the outside book display in her heavy cloak and long full skirt.

Gisèle Freund and Man Ray were among those who fled from Paris when the Germans invaded France. Though Shakespeare and Company eventually surfaced and survived after the war, it was forced to "disappear" during the occupation. When Sylvia refused to sell a German officer a copy of James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, he was furious and told her they were coming that same day to confiscate "everything." With the help of friends, she took down all the photographs and carried them with the books in clothes baskets to a vacant apartment on the third floor. She even had a carpenter dismantle the shelves while a house painter painted out the name Shakespeare and Company. By the time the Germans came back there was nothing left to take. The thought of how close we came to actually losing the material displayed in this exhibit underscores the inadequacy of the facile, catch-all term used to describe it. "Lost Generation" is a convenient label but it seems empty next to the literary and artistic excitement of the world that lived between the book-and-picture-lined walls of Sylvia Beach's bookshop.

In A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway provides perhaps the best account of that world and of what it was actually like to browse and do business at Shakespeare and Company. He also offers this portrait of the person who made it all possible, a picture "taken" the day he first walked into the shop and met the young woman from Princeton: "Sylvia had a lively, sharply sculptured face, brown eyes that were as alive as a small animal's and as gay as a young girl's, and wavy brown hair that was brushed back from her fine forehead and cut thick below her ears and at the line of the collar of the brown velvet jacket she wore. She had pretty legs and she was kind, cheerful, and interested, and loved to make jokes and gossip. No one that I ever knew was nicer to me."

"Portraits of the Lost Generation" will be on view through April 17 at no charge in Firestone Library's Main Gallery from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday and from noon to 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. It was organized by Don Skemer, curator of manuscripts in the library's Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, and John Logan, literature bibliographer in the library, with the assistance of graduate student in English Keri Walsh.