|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 12

|

|

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 12

|

|

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

|

|

Fifty years ago this February, the 27-year-old tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins got together with drummer Max Roach and bassist Oscar Pettiford to record a composition he called “The Freedom Suite.” When the album of the same name came out on Riverside Records later that year, the back cover carried a brief, pointed statement about race from Rollins, that “opened the door for jazz recordings of conscience,” according to Gary Giddins in Visions of Jazz (Oxford 1998; paper 2000). Opening that door required a politic spin. Co-producer Orrin Keepnews wrote the liner notes, and his labored introduction to music encumbered by the loaded term “freedom” suggests, at least in this election year, the hand of a campaign manager attempting to finesse his candidate’s position on a volatile issue. Given the state of race relations in America in 1958, Keepnews felt compelled to needlessly assure the record-buying public that this “is not a piece about Emmett Till, or Little Rock, or Harlem, or the peculiar local election laws of Georgia or Louisiana.”

The brief statement signed “Sonny Rollins” displayed in a box on the album’s back cover begins by asserting that Eisenhower-era America is “deeply rooted in Negro culture: its colloquialisms, its humor, its music” and goes on to point out the “ironic” reality that “the Negro, who more than any other people” could “claim America’s culture as his own,” is being “persecuted and repressed; that the Negro, who has exemplified the humanities in his very existence, is being rewarded with inhumanity.”

“I wanted my feelings to be clear,” Rollins tells Eric Nisenson in Open Sky (DaCapo 2000): “I really sweated over it.” Even so, “I got a lot of flak for it.” On a subsequent tour that took in border states like Virginia, he was confronted by white fans, some of them “obviously upset. I felt pressure to rescind my statement, but of course I did not do that.” Considering the line-up he was touring with, some tension was inevitable. Besides getting more than his share of notice as the only black leader in a package group that included Maynard Ferguson’s big band, Dave Brubeck, and the Four Freshmen, he was fronting a “revolutionary” drum-bass-tenor trio “playing things at breakneck tempos.” He mentions wanting to “sit down and write about that tour because so many interesting things happened.” Maybe he and Gary Giddins will talk about it during their “Conversations in the Humanities” event next week at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York.

Blowing Through

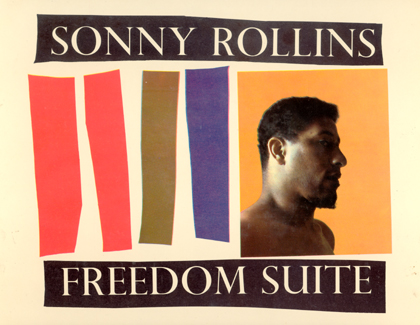

Freedom Suite’s cover, one of the most brilliant examples of album art produced during the golden age of jazz, is a statement in itself, with Rollins bare shouldered and stalwart in the center, framed like a tribal sculpture, the prototype of the jazz warrior. The imagery seems to promise music on the order of Max Roach’s 1960 album, We Insist: Freedom Now. But Rollins isn’t insisting. So small a word doesn’t figure in his musical vocabulary.

“The Freedom Suite” is pure, positive force, the enlightened convergence of three inspired musicians. In the succinctly arranged opening movement, the theme sounds as stately as an anthem and as simple as a nursery rhyme; you could put words to it children might sing in a round with “freedom” spelled out in the two beats at the end of every second line. It’s as if Rollins were deliberately playing against the expectations of listeners looking for something raw, brazen, or politically explicit. Once he outlines what Keepnews calls the “single melodic figure” he’ll be coming back to, developing, and reconfiguring, Rollins becomes “Sonny,” which is to say, feisty and funny, an attitude old-time racists might call “uppity.” The anthem sustains its dignity even as the tenor nudges and winks, sly and seductive. Only Sonny Rollins could toss off a quote from “The Donkey Serenade,” and then, after a couple of rollicking interludes on either side of a plaintive ballad, build a full-tilt closing movement around variations on “Polly want a cracker” — you can almost hear kids on a playground going nah-nah-nah-ne-nah-nah, all in an element of flawless virtuosity with Roach and Pettiford brilliantly equal to the task. The playing isn’t about freedom, it is freedom. No need to protest “prejudice” and “inhumanity.” Just blow through the wall of language and let the world come in because the ultimate humane essence of freedom is for everyone, “regardless of race, creed, or color.” In the spirit of Walt Whitman, Camden’s good grey poet, the playing says it’s time to “unscrew the doors themselves from the jambs!” and remind everyone that “whoever degrades another degrades me!”

Translate this joyous, hopeful, welcoming music into the present — again, with the primary season in mind — and you discover a quality not unlike Barack Obama’s celebration of hope and change and unity against the red state/blue state impasse of 2008.

The Teacher

At the time in the early 1960s when John Coltrane was the ascendant jazz phenomenon and Sonny Rollins the mysterious self-exiled figure woodshedding on the Williamsburg Bridge, there were those who seemed to think you had to choose between them, like rival candidates for office. Except that Rollins had taken his name off the ballot. If you lived in New York in those days and were walking through the Village, you couldn’t get far without hearing the sound of Coltrane’s sax wailing out of the windows along the way. If you were enjoying Coltrane in person and Rollins on record, you didn’t worry about which one the critics and fans were casting their votes for in that primary season of tenor madness.

Due probably to a relatively disappointing recording career post-1965, it’s become accepted wisdom that Sonny Rollins’s genius has never been captured on record. He himself has admitted that he hates playing in the confines of the studio; nor is he comfortable when he knows he’s being recorded in live performance. It’s true that people who come away dazed and talking to themselves after witnessing one of his miraculous sets are usually aware that even the most sophisticated recording of the miracle is not going to be much better than a snapshot. You might as well take pictures of a sunset.

The truth, however, is that between 1955 and 1965, the wonder of Sonny Rollins can be heard on at least a dozen recordings, either as a leader or as a sideman. It’s hard to believe Eric Nisenson is serious when he says that making records was merely “a professional obligation” for Rollins at the time of Freedom Suite and that “the studio was not a place for aesthetic epiphany.” One thing that explains the richness of his output from this period is the way he can bring you in and teach you how to hear him. As Martin Williams points out in a Down Beat review of Freedom Suite, this is where the “real achievements” have come, because “he is one of the few hornmen in the history of jazz (perhaps the first) who can give a long improvisation a sense of structure and development.” When you’re hearing him do what Williams describes in another article as learning “how to get inside a theme, abstract it, distill its essence, perceive its implications,” it’s as if Rollins is telling you, “Here’s what I’m doing. Come with me. This way. Look, I’m going here, now I’m over here, now I’m doing this.”

Sonny Rollins produced other wonders in 1958. In Newk’s Time his sound is big enough to live in. Jazz musicians love to quote unlikely sources, but Rollins inhabits and transforms them, as he does so memorably on that album in “Surrey With the Fringe On Top,” and, in songs like “Chapel in the Moonlight” and “I’ve Found a New Baby” on Sonny Rollins and the Contemporary Leaders, another landmark record from 1958.

Rollins at CUNY

Now that we’re living through this rollercoaster of an election year, it would be nice to hear what the composer of “The Freedom Suite” thinks of the fact that a black man is running for president. It would also be interesting to hear how Obama’s message relates to the spirit of that music or to Sonny Rollins’s words, as quoted in Open Sky: “If you want to build a better society, a better world, a better music … you just cannot put everything into black or white.” And what happened on that tense package tour in 1958? Perhaps we’ll find out when Rollins and Gary Giddins get together for their talk from 6:30 to 7:30 p.m. next Wednesday, March 26 at Proshansky Auditorium, in the CUNY Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue in midtown Manhattan. It’s a free event and seating is first-come, first-serve.

Freedom Suite is available on CD at the Princeton Public Library.