|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 12

|

|

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

|

|

A library was a living world to him, and every book a man, absolute flesh and blood.Samuel Taylor Coleridge

The common wisdom among the dealers, bibliophiles, and market-savvy bargain hunters lining up for today’s 10 a.m. preview of the Bryn Mawr Wellesley Book Sale is that no earthly, mortal supervisory authority could accurately price more than a fraction of the multitude of books filling tables in the Princeton Day School gym and dining hall. With this loophole in mind, the people in line can imagine that all manner of treasures will slip undetected through the net. If you’ve ever stood among the crowd gearing up to rush the tables, you’ll have heard stories of fabulous finds from dealers who have contributed to the sale’s mystique over the years by showing up at ungodly hours of the morning on the big day (or the night before) to claim a place at or as near as they can get to the front of the line. That, however, was during the time of the dealer-devised system of numbered tickets, which is no more now that the sale’s high command has imposed a lottery system.

Regardless of what’s done to improve the mechanics of admission, nothing is likely to dilute the all-bets-are-off tension of those minutes before the gates are opened. Even though veterans of the event know that much of what’s out there isn’t, as the saying goes, worth the paper it’s printed on, they nurture the fond hope that this will be the day they find the Big One; the same goes for those hardcore book lovers whose idea of a great find is a printed version of their heart’s desire rather than something to be sold for profit.

“Something Will Turn Up”

For some 30 years, give or take a few, I’ve been in that line, dreaming that dream, but when I think back to the things I’ve actually found, I realize that what made the sale so pleasurable and absorbing was simply the high of anticipation, that heady atmosphere of possibility where you feel you can count on finding at the least one or two nicely unlikely, quirky, surprising, subtly alluring volumes among the masses. After the tension and chaos of the first hours have passed, there’s also the pleasure of simply browsing at your leisure, content in the knowledge that something interesting may turn up. The wording of that Dickensian sentiment inevitably brings to mind Princeton’s late lamented Micawber Books, where several heart’s-desire-category treasures did turn up, notably the first American edition of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick or The Whale, which Logan Fox pulled out of a brown paper grocery bag one day in the summer of 1986.

The Best Find

In all these years, I’ve found no Faulkner first editions at Bryn Mawr, no firsts of On the Road or Catcher in the Rye or The Great Gatsby, or any other high-ticket item (unless you count a trashed, jacketless first of Dashiell Hammet’s The Thin Man), not even in Collector’s Corner, where the rarities are kept. Among the finds from past sales that I still own are two battered early Emersons (loose covers, cracked spines, foxed pages, some featuring the brownish imprint of flowers pressed between them in 1850) and an early edition of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage.

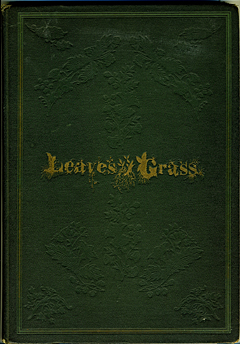

The most memorable book that ever turned up for me wasn’t even a first edition, but the facsimile of the 1855 Leaves of Grass, published in 1919 by Thomas Mosher. Almost 100 years old now itself, it’s acquired enough of the charisma of antiquity to pass for the real thing to a careless or unenlightened observer. One of the outstanding qualities of the book is its size. It’s as large as a laptop. While the idea of containing Whitman between covers is already a contradiction in terms, this volume truly is big enough to give his expansive lines room to roam in. Whitman once said that he preferred his poetry to be in a volume small enough to be carried in one’s pocket. No one but the likes of Gargantua or Gulliver has pockets deep enough to hold the first incarnation of Leaves of Grass, which is how the poet wanted it. He not only paid for this, his maiden voyage, he actually helped set the clear, bold type. You can feel the hand-bill immediacy of the document, 800 copies of which were sent out into the unsuspecting world from a Brooklyn print shop. The lettering on the title page is immense, you might even say outlandish. Most first-time poets would identify themselves by name. Whitman chose to give the extra space to his title. Not that he’s shyly hidden in the shades of anonymity. He’s there in person in the steel engraving on the frontispiece (possibly the first author “photo” ever seen in an American book). Looking like a mixture of working man and Bohemian, a big hat clapped on his head, which is slightly cocked, the 37-year-old poet confronts the reader with an intimidating gaze, one elbow bent, the other hand in his pocket.

The Poem Is America

I still have my father’s marked-up copy of the Heritage reprint of Leaves of Grass, with Whitman’s original preface, but in that normal-sized volume (reduced from its original Heritage Club bulk due to a wartime regulation), it looks cramped. In the facsimile it can sprawl, a prose poem sprinkled with dashes, exclamation points, and ellipses. Words and lines that look small and tame in the Heritage jump out at you from the facsimile, as in the second paragraph, where man, poem, and country become one: “The Americans of all nations at any time upon the earth have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem. In the history of the earth hitherto the largest and most stirring appear tame and orderly to their ampler largeness and stir. Here at last is something that corresponds with the broadest doings of the day and night.”

Of course Whitman didn’t know that this great “poem” was about to go to war with itself, but it’s possible to see a portent in its “ampler largeness and stir” and “broadest doings.”

No wonder Emerson hailed the book’s “great power” and “free and brave thought.” Imagine him reading the first sentences of the preface, nodding his head to his own music, sounded back in 1845 in his essay, “The Poet,” supposedly Whitman’s inspiration (“I was simmering, simmering, simmering. Emerson brought me to a boil”).

Besides reflecting the breadth and amplitude and largeness Whitman is celebrating, the copy of Mosher’s facsimile I found for a pittance years ago at Bryn Mawr (years before Wellesley joined in) contained, as these old castaways often do, some extra added attractions such as an offprint from 1925 about the New York Public Library’s Walt Whitman Exhibition; the first page of the February 24, 1946, New York Times Book Review (“Walt Whitman: Poet of America”) with a Civil War-period photo of the poet from the Matthew Brady archives; a clipping from a circa 1966 Times review of the play, A Whitman Portrait, at the Gramercy Arts Theatre; and best, a clipping that shows Robert E. Johnston’s mural in the Walt Whitman Hotel in Camden, in which “The Good Gray Poet Surveys America.” Looking like Moses, or a Hindu holy man, Whitman, who spent his last years in Camden, looms up out of the tree of life overlooking a vision of human existence “in these states” that could serve as well to illustrate Shakespeare’s Seven Ages of Man. The fact that the hotel and the mural are presumably long gone makes this stowaway clipping a poignant addition to the book.

Tune in Next Week

Although it’s doubtful that something as fine as the Whitman will turn up this year, I’ll be roaming the sale this week looking for some quaint and curious volume or volumes to feature in next week’s column. You never know what the vicissitudes of the set-up will bring your way. Last year it was a poetry anthology from 1845 whose unseemly condition had caused it to be priced at one dollar and marked, “Declined by Collector’s Corner.”

For a true book sale pilgrim, condition isn’t everything. There are times when a touch of sweet shabby disorder actually supplies the desired charisma. What’s more, the very notion of a book as a weathered, steadfast, indomitable survivor from Coleridge’s “living world” is all the more bracing and relevant at a time when our newly elected governor is putting his budgetary axe to New Jersey’s libraries. Keep Christie’s iron fist in mind when you behold all those books on the tables at the Bryn Mawr Wellesley sale this week. Events like this one, and our own Friends of the Princeton Public Library Book Sale in October, celebrate books as a central community resource and, in the case of the library, provide some financial assistance as the budget noose tightens.

The library will be celebrating National Poetry Month in April with a number of events, including a reading by C.K. Williams on the occasion of his new book, On Whitman (Princeton University Press) and his latest volume of poetry, Wait (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). The event will take place in the Community Room on April 20 at 7:30 p.m.