|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 18

|

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

|

‘I am the orchestra! I am the chorus and the conductor as well. My piano sings, broods, flashes, thunders. It rivals the keenest bows in swiftness; it has its own brazen harmonies and can conjure on the evening air its veiled enchantment of insubstantial chords and fairy melodies, just as the orchestra can and without all the paraphernalia …’—Hector Berlioz, Memoirs, from a letter to Franz Liszt (1843)

Speaking as Liszt, an orchestra unto himself, Berlioz offers this word picture of his friend’s musical and personal magnetism as a way of setting off what he, Berlioz, the touring conductor, has to put up with when confronted with the “perplexities” of a strange town and a decimated orchestra (“The first clarinet is ill, the oboe’s wife is in labour, the first violin’s child has the croup, the trombones are on parade …, the tympanist has sprained his wrist, the harp isn’t coming”).

Berlioz goes on to picture what happens as Liszt, who was 32 and in his performing prime, concludes a performance. “No one breathes; a passionate silence reigns, a deep, still hush of wonder. Then come the explosions, the glittering set-piece that crowns the firework display, the cheers of the audience, the hail of flowers and bouquets raining round the high priest of music, rapt and quivering on his tripod, the girls in their holy frenzy kissing the hem of his garment and moistening it with their tears, the sincere tributes of the serious-minded, the feverish applause wrung from the envious, the narrow hearts expanding in spite of themselves.”

He’s There

The other day I experienced something like the “hush of wonder” Berlioz imagines following one of the “dazzling inventions” that “spring to life” at Liszt’s fingertips. In my personal concert hall (the front seat of a Honda CRV), the hush follows a performance of a piece for solo piano, “Fountains of the Villa d’Este”(1877) from Années de pèlerinage (Years of Pilgrimage), which in a little less than eight minutes creates a world of beauty. Inside the lavish soundscape, as if it were lost, there for Liszt to find, is one of those primal melodies that goes straight to the source of all longing, and to quote Berlioz, expands the heart. Then, as the piece ends, fountains of splendor and glory encompass the little melody, simple notes a child could play, while a series of ascending, otherworldly trills runs right up your spine and leaves you shivering and silly with joy. Although the pianist credited on the EMI recording is André Watts, who played at McCarter in April, to my ears it was Liszt himself, and so it always seems when the work is for piano. With solo pieces by Chopin it’s possible to imagine that the composer is at the keyboard, but with Liszt, nothing need be imagined. It happens; he’s there, the performer and composer in one.

Dr. Moriarity as Liszt?

Earlier this year I found myself warily, or, at best dutifully, approaching the subject of a 200th anniversary celebration of Liszt (1811-1886). Why should this be so? Last year I wrote enthusiastic columns to mark Schumann and Chopin’s 200th and Gustav Mahler’s 150th. It’s true that I had no conception of this composer’s greatness then, being better acquainted with the early Who than the early Liszt. And behold, in the casino of Pop culture, all it takes is a toss of the dice and the Who’s Roger Daltry surfaces in 1976 as a travesty of Liszt in Ken Russell’s monstrosity Lisztomania.

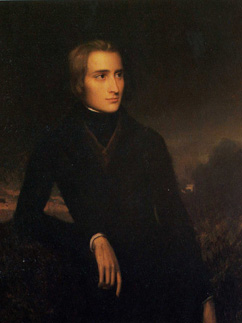

To be fair, there were other, even more absurd forces degrading my image of Liszt. Around the time I was writing about Schumann, I made it a point to see the Hollywood biopic, Song of Love (1947), in which Liszt is impersonated by Henry Daniell, a gentleman who played the criminal mastermind Dr. Moriarty opposite Basil Rathbone’s Sherlock Holmes. All Daniell has to do to evoke moral revulsion in an audience is to smile. A smile from Daniell is like a smile from Nixon, enough to give smiling a bad name. So here’s this actor whose stock in trade is to be at once sinister and smug, the cat who swallowed the canary, and he’s playing one of the 19th century’s most charismatic figures, the epitome of the supremely handsome performer, a Valentino of the keyboard whose impact on the fairer sex was of Beatlesque proportions (as Berlioz notes, women wept). Worse yet, in a screenplay mostly written by Ivan Tors, who went on to make a nice living with creature features and the Flipper movies, Daniell’s Liszt is portrayed as a repellent, preening bounder even while his first piano concerto is being used to show off the pianistic virtuosity of Katherine Hepburn (as Clara Wieck Schumann) in the film’s opening sequence. Daniell’s only scene of substance finds him at an intimate musical evening performing an elaborate Lisztian paraphrase of a simple ballad, “Dedication,” which its composer Robert Schumann (Paul Henreid) had tenderly performed for Clara in the previous scene. When Daniell’s smirking nightmare of Liszt treats the simple piece to an orgy of pianistic effects, a fussy, holier than thou Clara loudly whispers in her husband’s ear (“A dedication to pyrotechnics!”) while young Johannes Brahms (Robert Walker) pelts the creep at the keyboard with psychic spitballs. To top things off, no sooner has Liszt finished than Clara claims the piano so as to play the ballad as it should be played, smugly chiding him (“It’s about love, Franz. Love as it is. No glitter. Just love”) while the glowering virtuoso stands there looking bilious and beaten.

As usual, Hollywood knows no shame, mocking and humiliating a composer whose music has been pillaged time and again by the soundtrack hacks inflicting their overblown scores on generations of movies and moviegoers.

In the 1960 biopic, Song Without End, which I’ve seen only excerpts from, Dirk Bogarde plays Liszt, which, if nothing else, is a big improvement on Daniell and Daltry.

The Sweet Smell of Excess

Admittedly, there’s a Jekyll and Hyde component to Liszt’s genius, which Charles Rosen’s The Romantic Generation considers in a chapter on Liszt titled, “Disreputable Greatness.” According to Rosen, “The early works are vulgar and great; the late works are admirable and minor.” While Liszt was “indeed a charlatan,” it is “useless to try to separate the great musician from the charlatan: each one needed the other in order to exist.”

The charlatan in Liszt doubles as Mephistopheles in one of the most exhilarating piano works ever written, the first Mephisto Waltz (1859-62), which has the vehement audacity of a late Beethoven quartet, the scintillating fairytale wonderment of Berlioz’s “Flight of Queen Mab,” plus surging, gushing bursts of melody George Gershwin surely picked up on 50 years later, and “one of the most voluptuous episodes outside of a score by Wagner,” according to James Huneker, who calls the “halting languorous syncopated” theme in D flat “marvelously expressive.”

When Huneker discovers the charlatan in the Hungarian Rhapsodies, with their “pompous, affected introductions, spun-out scales and transcendental technical feats,” he does so on his way to celebrating “the strong man of music,” the “supreme painter” of “the infernal and the macabre,” who courts and vanquishes “the Evil One” in the Sonata in B minor: “Nothing more exciting is there in the literature of the piano. It is brilliantly captivating, and Liszt the conqueror, Liszt the magnificent, is stamped on every octave.”

In “A Letter on Conducting” (1853), Liszt chastises players and conductors who refuse to tackle difficult works that transcend “the imperturbable beating of time” and the “vulgar maintenance of the beat,” works that clash “with both sense and expression.” Then he takes up his own cause: “There, as elsewhere, the letter kills the spirit [Liszt’s emphasis] and to this I could never subscribe, however plausible might be the hypocritically impartial attacks to which I am exposed.”

The attacks Liszt refers to are dust in the wind given the stature of his defenders and admirers through the centuries. After taking his flaws into account, his fellow Hungarian Béla Bartók cites “the new ideas” to which Liszt was “the first to give expression” and his “bold pointing toward the future” as among the qualities that raise him “as a composer to the ranks of the great,” which is why “we love his works as they are, weaknesses and all.”

George Eliot Gets Close

The author of Middlemarch visited Liszt in Weimar in 1854, sat next to him at breakfast, and, as she observes in her journal, “Then came the thing I had longed for — Liszt’s playing. I sat near him so that I could see both his hands and face. For the first time in my life I beheld real inspiration — for the first time I heard the true tones of the piano. He played one of his own compositions — one of a series of religious fantasies. There was nothing strange or excessive about his manner. His manipulation of the instrument was quiet and easy, and his face was simply grand — the lips compressed and the head thrown a little backward. When the music expressed quiet rapture or devotion a sweet smile flitted over his features; when it was triumphant the nostrils dilated. There was nothing petty or egoistic to mar the picture.”

The fact that George Eliot had to address terms like “strange or excessive” and “petty or egoistic” shows the stereotype of Liszt that Hollywood was still playing with in 1947 and that still has to be either discounted or embraced. The negatives remain, as in the notion that Liszt’s interpretations and paraphrases of his peers were little more than glorified theft, as if he were a sort of magpie when in fact he illuminated everything he touched. All you have to do is to listen to the Paganini etudes, or the transcription of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantasie, which Liszt helped put on the map at a time when his friend was poor and neglected. Again, Berlioz says it best, writing, after hearing Liszt perform Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata, “Liszt, has solved it, solved it in such a way that had the composer himself returned from the grave, a paroxysm of joy and pride would have swept over him. Not a note was left out, not one added … no inflection was effaced, no change of tempo permitted. Liszt, in thus making comprehensible a work not yet comprehended, has proved that he is the pianist of the future.”