|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 18

|

|

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

|

|

To me the immediate impression is never a starting point for work. The impression has got to age, has got to falsify itself with time, without my having to falsify it.C.P. Cavafy (1863-1933)

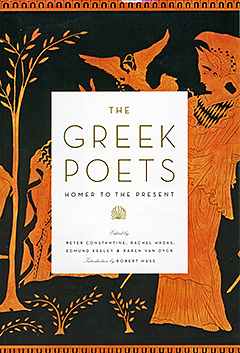

Lawrence Durrell, who completed his Alexandria Quartet 50 years ago with the publication of Clea, gave me a way into The Greek Poets (Norton $39.95), which contains 670 pages of poetry in translation from “Homer to the Present.” I’ve been gazing at this formidable volume for months, a clueless amateur at the base camp of a Greek Mt. Everest. No supplies, no decent climbing gear, no oxygen mask, no background in the subject beyond reading Homer in college, watching sunsets from the Acropolis, living in a garden on Myconos, and riding from Lamia to Thessaloniki with a drunken Greek truck driver gesturing wildly in the direction of the moonlit Aegean Sea, shouting “Thalassa! Thalassa!”

A worthy addition to the preeminent company of Norton anthologies, The Greek Poets features a thousand poems by 185 poets and 120 translators, including its editors, Princeton University Professor Emeritus Edmund Keeley, Rutgers Professor Rachel Hadas, award-winning translator Peter Constantine, and Karen Van Dyck, a professor of Greek literature at Columbia.

The Old Poet

That translations take liberties is in the nature of the process; it’s a dynamic that relates to your perception of virtually everything, beginning with what happens when the brain translates a memory. C.P. Cavafy’s “immediate impression” in the quote above could be read as an argument against attempting a literal translation of a given moment, the starting point from which a poem is falsely lost and truly found in the course of its making. The oblique trajectory reflects the course of Cavafy’s own journey as a Greek who grew up in England, lived most of his life in Alexandria, and was pictured by E.M. Forster as “a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless at a slight angle to the universe.”

Lawrence Durrell takes liberties with Cavafy in the Quartet, freely translating not only the poetry, but the poet himself in the form of a semi-fictional character he calls the “old poet of Alexandria,” whose role, as Durrell described it in an interview, is to express “the essence of the city.” In the “Consequential Data” at the end of Justine, the Quartet’s first volume, Durrell, writing in the guise of his alter ego Darley, admits that his translations are “by no means literal” and contrasts them to “the fine thoughtful translations of Mavrogordo,” which “in a sense” has freed Cavafy “for other poets to experiment with.” As if to counter the negative implications of “experiment,” Durrell tweaks the terminology, asserting that he has “tried to transplant rather than translate.”

The “experimenting” done on “The City” and “The God Abandons Antony” in Justine is in clear contrast to the more circumspect translations of the same poems by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard in The Greek Poets. For example, the “invisible procession going by/with exquisite music” in the Keeley/Sherrard translation of “The God Abandons Antony” becomes in Durrell’s version “The invisible company passing, the clear voices./Ravishing music of invisible choirs.” Readers with their ears tuned to Durrell’s lush prose may find a haunting resonance in the way his “falsified” Cavafy echoes the music of Justine, in particular the passage midway through the narrative where a dying man begins to softly sing “a popular song which had once been the rage of Alexandria,” a song that suddenly evokes “the dying Antony in the poem of Cavafy” (“How different from the great heart-sundering choir that Antony heard — the rich poignance of strings and voices”).

In “The City,” the Keeley/Sherrard version begins in the past tense: “You said: ‘I’ll go to another country, go to another shore’” and then: “Whatever I try to do is fated to turn out wrong.” Durrell proceeds to place the line in the present (“You tell yourself: I’ll be gone/To some other land, some other sea”) and then extends the benign violation by inserting his own metaphor: “Where every step tightens the noose.” The next line (“How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?”) is loftily elaborated by Durrell into “How long, how long must I be here/Confined among these dreary purlieus/Of the common mind.” While the showy rhyming of “noose” and “purlieus” may set a Cavafy purist’s teeth on edge, it’s hard to fault Durrell for doing some creative falsifying on the way to composing one of the central literary works of his time.

Homer

It all begins with the poet whose work above all others demonstrates translation’s wayward route through the ages and whose appearance in The Greek Poets (at 49 pages, the longest in the book) comes with a note to the effect that “Homer is the name that has been ascribed since antiquity to the author of the epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, though whether either of these works was composed by a single author has become the subject of much debate.” Of course no amount of debating will ever document all that has been lost or discovered in translation in the course of a journey that has no known starting point other than “antiquity.” In his sonnet, “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer,” John Keats isn’t celebrating fidelity to some hallowed original. His Homer is at once a “deep-browed” mortal and “a wide expanse” whose “pure serene” can be inhabited and breathed in through Chapman’s “loud and bold” translation, which Keats spirits into his own vision of a “watcher of the skies/ When a new planet swims into his ken.”

A Lesson in Translation

On looking into the second massive volume of Princeton University Press’s edition of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Marginalia, I found an example of the disparity between Greek and English scribbled by Coleridge “at the head of the dedication leaf” in the copy of Chapman’s Homer he gave to the love of his life, Sara Hutchinson. In his inscription, he stresses the impossibility of doing justice to the Greek: “a language blessed above all others in the happy marriage of sweet words, and which in our language are mere printer’s compounds,” such as “divine wine.” Coleridge points out that “divine” in Greek encompasses “joy-in-the-heart-of-man-infusing” in “one sweet mellifluous Word.” Once he’s pointed out this essential disadvantage, however, he credits Chapman’s Homer for having “no look, no air of a translation. It is as truly an original poem as the ‘Faery Queen.’” Chapman “writes & feels a Poet — as Homer might have written had he lived in England in the reign of Queen Elizabeth.”

Revelations

There’s no way to do justice to the richness of The Greek Poets. Revelations and surprises abound, as in John Talbot’s wildly free translation of Theocritus (“Idyll XV The Festival Housewives”), where a reference to Einstein jumps out at you from the early third century and you get lines like “Fat cats like it cushy” and “Sheesh the traffic.” Homeric Hymns from the seventh century BCE are followed by an anonymous mock epic cartoon (except instead of Tom and Jerry, it’s “The Battle of Frogs and Mice”) featuring King Pufferthroat, Lord Mudworth, and the Princess of the Mice.

Some of the most refreshing finds are in the lively, erotic early Byzantine poets Rufinus (“How often I longed to have you at night, Thalia,/to satisfy my passion with wild lovemaking/Now that your sweet limbs are naked next to mine”) and Diphanes of Myrina (“Eros is rightly called a three-faced robber:/He lies awake, he’s audacious, he strips you bare”), and Paulus Silentiarius (“I caress her breasts, mouth on mouth,/out of control I madly feed on her silver neck”). Those last three examples of early Byzantine eroticism were translated by Edmund Keeley. Other Princeton faculty members with translations in The Greek Poets are Paul Muldoon, C.K. Williams, and of course the late Robert Fagles.

Penelope’s Loom

Penelope stands out among the characters bridging the ages in this vast book. Besides her appearance in several poems by Katerina Anghelaki-Rooke (who was born in 1939), she turns up in Edmund Keeley’s translation of “Penelope’s Despair” by Yannis Ritsos (1909-1990). Improvised on Penelope’s wary reception of the just-returned Odysseus in Book XXIII of the Odyssey, the poem begins, “It wasn’t that she didn’t recognize him in the light from the hearth; it wasn’t/the beggar’s rags, the disguise,” it was the question she asks herself, which was how she could have “used up … twenty years in waiting and dreaming, for this miserable/blood-soaked, white bearded man?” She finally says, “Welcome,/hearing her voice sound foreign, distant. In the corner her loom/covered the ceiling with a trellis of shadows; and all the birds she’d woven/with bright red thread in green foliage, now,/on this night of the return, suddenly turned ashen and black,/flying low on the flat sky of her final enduring.”

In those closing lines you feel poet, translator, and the Homeric moment all in perfect alliance.