|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 21

|

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

|

|

|

The world is a Dancer; it is a Rosary; it is a Torrent; it is a Boat; a Mist; a Spider’s snare; it is what you will … Call it a blossom, a rod, a wreath of parsley, a tamarisk crown, a cock, a sparrow, the ear instantly hears and the spirit leaps to the trope.Emerson, Journals, Summer 1841

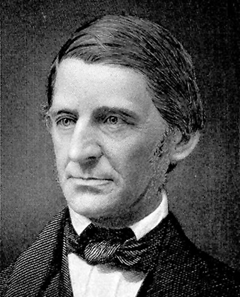

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edward Bulwer-Lytton were born on the same day, May 25, 1803. On May 25, 2011, Emerson lives on, a force of literary nature, and Bulwer-Lytton, who wrote some 30 novels in his time, is best remembered for a sentence fragment of seven words. When Emerson visited London in 1833, he sought out Coleridge, Wordsworth, and Thomas Carlyle, but not his birthmate, author of the best-selling novel, Paul Clifford (1830), which Bulwer-Lytton chose to begin, some 135 years before Snoopy got his paws on a typewriter keyboard, “It was a dark and stormy night.”

A consensus of online sources says that Lord Lytton, who died in 1873, nine years before Emerson, also coined the phrases, “the Great Unwashed,” “the pursuit of the almighty dollar,” and “the pen is mightier than the sword.”

Lytton Unbound

By all rights Emerson should be the subject of this column, but what a piece of work is Bulwer-Lytton. He begins his career as a radical, is elected to Parliament as a Whig, turns down Prime Minister Melbourne’s offer of a lordship of the admiralty so he can give full attention to his writing, and after 11 years out of politics stands for Hertfordshire as a Tory and holds that seat until he’s raised to the peerage as Baron Lytton of Knebworth. He then becomes Secretary of State for the Colonies, taking a special interest in British Columbia where a town on the Gold Rush route is eventually named for him. To top it off, he writes a posthumously published proto science fiction novel called The Coming Race in which a subterranean civilization flourishes through a mysterious electric power known as “vril,” another fragment of Lytton fiction that has achieved unlikely and uncredited renown thanks to the marketing genius who borrowed it for the ubiquitous British staple energy source, Bovril.

Last but definitely not least, there’s the matter of Lord Lytton’s dark and stormy relationship with Rosina Doyle Wheeler (1802-1882). After five years of marriage, they separate and she writes a novel savaging him as a hypocrite and a philanderer. Some 20 years later, when he stands for Parliament, she invades the hustings to accuse him of murdering their daughter and sodomizing Prime Minister Disraeli, upon which he has her committed to a madhouse. Released after a public outcry, she proves to be not only a prolific rival (14 novels all told) but a relentlessly vindictive adversary who has the last word in her memoir A Blighted Life (1880).

In his Observer review of Leslie Mitchell’s The Rise and Fall of a Victorian Man of Letters (2003), John Gross depicts Bulwer-Lytton as “part grand seigneur, part bohemian, part dandy, part diligent man of affairs” who “often received visitors while smoking a pipe six or seven feet long, or taking opium through a hookah. He was rather like a character out of a novel himself — not a very good novel, perhaps, but one with a certain undeniable lurid power.”

An Unjust Fate

Thus it is that thanks to the first sentence of Paul Clifford and an American academic with a bright idea, the flawed novel of Lytton’s life and work is primarily associated with bad writing, his main claim to fame in the culture at large being the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest wherein contestants contrive to write “terrible openings for imaginary novels.”

In 2008 Bulwer-Lytton’s great-great-great grandson, the Honourable Henry Lytton Cobbold of Knebworth House, went to the town of Lytton B.C. to debate the founder of the contest, San Jose State English Professor Scott Rice. I’m pleased to say that Lytton-Cobbold not only won over the crowd but carried the debate, leaving Rice to confess a grudging admiration for the writer he’d been ridiculing and, it seems, continues to ridicule.

After losing the debate, the sporting thing for Rice to have done would have been to rename the Bulwer Lytton Fiction Contest, which surely needs no help from Lytton now that it seems to have taken on a life of its own; perhaps it could be titled to take advantage of the craze for its pop culture equivalent, one of those reality shows contrived to grossly accentuate the negative and demean the humanity of the contestants. Instead, the annual event has continued its pointless guilt-by-association demeaning of the author whose novels were widely read during a period when he was competing for readers with writers like Dickens, Thackery, Wilkie Collins, and Trollope and producing The Last Days of Pompeii, a 19th-century classic (not to mention a Classic Comic: number 35, the issue, in fact, for which the name was upgraded to Classics Illustrated). Nor was Lytton’s audience confined to the United Kingdom, his writings having been translated into a dozen languages, including Serbo-Croatian. His play, Money, recently had a successful revival at London’s National Theatre.

To fully appreciate what I mean by guilt-by-association, you need only go to the contest site and read the painfully contrived opening sentences that have copped the prize for badness over the years, and it becomes clear that the event is little more than a benighted writers’ variation on the old Gong Show. Here is the 2010 winner:

“For the first month of Ricardo and Felicity’s affair, they greeted one another at every stolen rendezvous with a kiss — a lengthy, ravenous kiss, Ricardo lapping and sucking at Felicity’s mouth as if she were a giant cage-mounted water bottle and he were the world’s thirstiest gerbil.”

Agreed, that’s a terrible piece of writing, but it’s not even, so to speak, a good piece of terrible writing. Were you amused? Did you laugh? It not only fails as a parody, it has nothing remotely in common with Lytton’s line, whatever you think of it. Sending a stormy trope into the world is nothing to be ashamed of, and as its wikipedia entry shows, the same line or variations of it has been used by Washington Irving and Anne Radcliffe; in French by Alexandre Dumas in The Three Musketeers and George Sand in Consuelo; and more recently, by Ray Bradbury, Madeleine L’Engle, Joni Mitchell, and, of course, Charlie Brown’s dog.

The Whole Sentence

At this point, it’s only fair to quote in full the sentence in question:

“It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents — except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.”

Granted, the sentence has problems but it gets the job done. In 1830 “It was a dark and stormy night” was simply a good old fashioned storytelling refrain, with associations as primal as the telling of tales around the campfire, in the prehistoric cave, or, as I write, May 21, while waiting for the End of the World. Even the awkward break in the mood and forward movement created by a wooden phrase like “except at occasional intervals” could be defended as a way of effecting a syntactical version of the checking of the rain by the wind. I doubt that Edgar Allan Poe would have questioned the gust of wind “rattling along the housetops” or the “scanty flame of the lamps.” The notion of a struggle against the darkness foreshadows the story of a man accused of murder and very nearly hanged. As for Poe, if you go by the Scott Rice notion of bad writing, the author of The Murders in the Rue Morgue offers numerous passages no less open to simplistic mockery than the first sentence of Paul Clifford.

A Supreme Opening

Probably Lytton’s most jarring violation of prose form is the intrusive, offhand nature of the reference to London. You can’t contain an entity as massive and evocative as London in a parenthesis, certainly not when it breaks the momentum created by that “violent gust of wind.” An example of inspired momentum in the cause of a dark and stormy effect can be found in one of the supreme opening passages in literature:

“London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes — gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.”

Such are the opening sentences of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House. It bestirs itself in fragments, then sprawls and soars, a wonder of bold, forthright, self-captivated writing, damn the torpedoes and full spread ahead. I mean, a waddling elephantine lizard?? No one pushes the limits like Bulwer-Lytton’s friend and colleague Charles Dickens, and he’s only warming up for an ecstatic prose poem on the fog that ends with “people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.”

Fog, a word as solid and primal as dark and stormy and night.

A relatively mortal, by-the-book writer like Bulwer-Lytton must have raised his eyebrows, smiled, and shook his head when he first encountered Dickens’s Megalosaurus. His birthmate Emerson might have laughed, as he’s said to have done after attending one of the public readings in Boston, on Dickens’s American tour. Emerson “was afraid that Dickens had too much talent for his genius; it is a fearful locomotive to which he is bound and can never be free from it nor set to rest …. He daunts me! I have not the key.”