|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 45

|

|

Wednesday, November 7, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 45

|

|

Wednesday, November 7, 2007

|

|

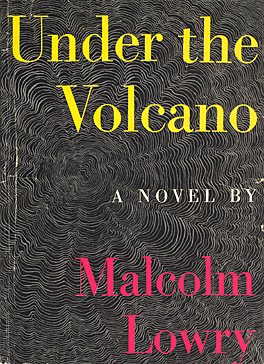

Last Friday, November 2, the Day of the Dead, which is the day in 1938 when the events in Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano take place, I checked to see if a copy was available at the Princeton Public Library and learned, to my surprise, that the only version of this 20th-century classic in the catalogue is in the form of a 2-disk Criterion DVD of the 1984 film directed by John Huston. I was also unable to find either of the biograpies of Lowry, who died 50 years ago, June 27, 1957.

I haven’t checked, but I wonder how many other works of literature are no-shows among the multiple copies of fast-food fiction in the collection. My hope is that the library, which has been such a valuable source for classic films on DVD, will order the 60th anniversary paperback edition of Under the Volcano (Harper $14.95), which comes with an afterword by novelist William T. Vollmann.

The subtext of the story behind the ten years it took Lowry and his wife to guide his book unscathed through the mid-1940s version of the fast-food fiction market has issues in common with the current controversy involving Gordon Lish’s doctrinaire editorial “minimalizing” of stories by Raymond Carver, including, apparently, the longer, clearly superior pre-Lish version of “A Small Good Thing.” Carver’s widow, Tess Gallagher, rightly believes that readers should have a chance to see the stories as they were before Lish summarily cut them down to size.

Evidence of the even more calamitous editorial fate that might have befallen Lowry’s masterpiece had not he stood his ground can be found in the volume of his Selected Letters edited by Harvey Breit and the novelist’s widow Margerie Bonner Lowry. Just read Lowry’s lengthy response to his British publisher’s anonymous readers’ reports complaining of the book’s “tedious” beginning, weak characterization, unconvincing flashbacks, excessive local color, and over-elaborate “phantasmagoria.” I can’t think of another major novel in any era where an author has provided so passionately detailed and enlightening a case for a work’s essential integrity.

Not an Easy Read

New readers coming to Under the Volcano may at first be tempted to agree with the editorial wisdom that said the novel would be “much more effective if only half or two thirds of its present length.” The early going is undoubtedly tough. There should be a warning, a variation on the sign Dante saw in the “dark wood” above the Gateway to the Inferno: perhaps not “Abandon All Hope Ye Who Enter Here” but “Abandon all Readerly Complacency” and summon your stores of patience. The author’s defense of his concept in the abovementioned letter even specifies Dante’s place in the plan. After pointing out that the book opens in the Casino de la Selva, Lowry explains that “Selva” means wood and thus “strikes the opening chord of the Inferno” in the “symphony” of his book. At once playful and dead earnest, he goes on to suggest that he’s written not merely a symphony, but “an opera — or even a horse opera.” It’s also “hot music, a poem, a song, a comedy, a farce,” as well as “superficial, profound, entertaining, and boring, according to taste,” not to mention “a prophecy, a political warning, a cryptogram, a preposterous movie, and a writing on the wall. It can even be regarded as a sort of machine.” And, of course, it’s a novel — “in case you think I mean it to be everything but a novel.”

Readers who have trouble getting into the book are in good company. The critic Alfred Kazin admitted as much to Lowry’s American editor: “I had no idea, when I spoke to you of my difficulty with the first pages of Under the Volcano, that it would end by overwhelming me as it has. I read the last pages with a sense of dread and vision, as if I had come to the end of a great tragedy. The book obviously belongs with the most original and creative novels of our time.”

The point at which the narrative begins to justify the superlatives (Stephen Spender said that it was “the most interesting novel” he’d read “since Lawrence and Joyce”) comes on page 35 when we finally enter the consciousness of the Consul, Geoffrey Firmin, in the form of a letter. You can be sure that the passage preceding the letter, which adds Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus to the heady mix already containing portions of Dante, Poe, Conrad, “The St. Louis Blues,” The Student of Prague, The Hands of Orlac, and Peter Lorre (and don’t forget the epigraphs from Sophocles, Bunyan, and Goethe), is one that the publisher’s reader would have red-pencilled for deletion as pretentious and unnecessary. The letter is only a sort of introduction to the prose magic inspired by the arrival of Firmin’s ex-wife Yvonne. I meant to quote one of the most brilliantly fevered passages, but there’s no way to do justice to Lowry’s accomplishment taken out of context. It’s the difference between reading about the Day of the Dead and being there.

Which brings us to the movie.

Words vs. Image

If ever there were a reversal of the old adage “A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words,” this is it. The Criterion DVD of Huston’s 1984 adaptation puts you right there, on a real, live Day of the Dead in Cuernavaca and several other sites in the state of Morelos. It’s all brilliantly available, real color and movement, real people, along with all the whimsically grisly effects of the holiday, skeletons and death’s heads, inclding a real dog following the drunken Consul (Albert Finney) through the streets (the dog is miscast; it’s a cute mutt, rather than the demonic pariah it’s supposed to be). Meanwhile Alex North’s score sounds like a failed fantasy on a theme of dipsomania south of the border with its jangly, tinkly, ghostly gypsy ambience. The fact that John Huston permits this to happen doesn’t mean that he’s out of sympathy with a great book. Just the opposite. He respects the text, closely following it in an attempt to put some of the most subtle and powerful moments on film, such as the one when the ex-wife (Jacqueline Bisset) appears like a vision in the doorway of the cantina where the Consul is slumped in a drunken trance. Finney is often thrillingly right for the role; it may be the most inspired and exhausting performance of his life. But nothing in the film at its best comes close to the brilliance of a single passage of the book at its best.

Needless to say, good intentions don’t always lead to great or even good movies. Think of the respectful attempts to film Joyce and Proust and Lawrence (let alone Fitzgerald and Melville and Hemingway). The best you can hope for is that a film evokes the atmosphere and spirit of the original, which seems to happen most happily in adaptations of writers like Jane Austen and Thomas Hardy or genre writers like Raymond Chandler. Here it’s not enough to insert a few drunken, semi-coherent snatches of Lowry’s prose into Finney’s drunken soliloquys or asides. You might be better off putting the book in the hands of some wild “B”-movie virtuoso with his own taste for excess who could take it all over the top in a mad film noir vision of the Consul’s descent, complete with lots of “glorious black and white” imagery.

Or perhaps what’s needed is a director with a Shakespearean vision in which the Consul is not an unredeemable drunkard lunging blindly toward his sordid doom but a word-drunk realm unto himself like Falstaff, whose rhetorical alchemy transforms wine into gold and, as he says in Henry IV Part 2, “ascends me into the brain” and “makes it apprehensive, quick” and “full of nimble fiery and delectable shapes, which, delivered o’er to the voice, the tongue, which is the birth, becomes excellent wit.” It also “illumineth the face, which as a beacon gives warning to all the rest of this little kingdom, man.”

To appreciate the scale of Lowry’s triumph in conquering his own demons and, with the help of his heroic second wife Margerie, bringing his version of “the little kingdom” into print, you only need read his letters or either of the biographies by Douglas Day and Gordon Bowker. Perhaps one day they, too, will be on the library’s shelves, along with the novel itself.

Rereading Under the Volcano made me curious to see “El Maestro Francisco Toledo: Art from Oaxaca, 1959-2006,” now on view at the Princeton University Art Museum. I’d also like to see Mexican director Ignacio Ortiz’s 2004 film Mezcal, which reportedly channels both Lowry and Shakespeare.