|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 46

|

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

|

|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 46

|

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

|

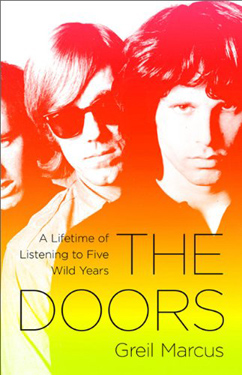

Greil Marcus on The Doors — Every Performance Tells a StoryStuart MitchnerWho isn’t fascinated with chaos? — Jim Morrison (1943-1971) Jim Morrison was speaking to Jerry Hopkins in a 1969 Rolling Stone interview. He had been saying that when you give people in the audience what they want, “they’ll let you do anything,” but “if you hold a mirror up and show them what they’re really like … and show them that they’re alone instead of all together, they’re revolted and confused.” Morrison then expands on what he means by chaos: “More than that, though, I’m interested in activity that has no meaning … free activity. Activity that has nothing in it but just what it is.” In the prologue to his new book The Doors: A Lifetime of Listening to Five Mean Years (Public Affairs $21.99), Greil Marcus describes a September 30, 1967 performance of “Light My Fire” at the Family Dog in Denver. As he does in his recent meditations on the music of Bob Dylan and Van Morrison (both also published by Public Affairs), Marcus uses bootleg recordings of live gigs that allow him to explore his subject in a variety of situations and venues. What makes Marcus an incomparable reader of rock and popular culture is his ability to weave a narrative. Instead of dry jargon-jumbled analysis, he creates storylines for the music in which he sometimes plays the vicarious protagonist, as when he observes that “the long instrumental passages, handed back and forth” between Robby Krieger’s guitar and Ray Manzarek’s organ in the Denver performance of “Light My Fire” are “hard to hold on to.” After alluding to maverick movie critic Manny Farber’s phrase “termite art,” Marcus takes his narrative to the area Morrison has in mind when he refers to “activity that has nothing in it but just what it is”: “It’s art without intent, without thinking, art by desire, appetite, instinct, and impulse, and it can as easily meander in circles as cross borders and leap gaps.” Tracing the chaotic, meandering storyline of the performance, Marcus treats the structure of “Light My Fire” almost as if it were a tangible entity Manzarek and Krieger are struggling to control or contain in the void that opens after Morrison sings the chorus; in the no-man’s land of improvisation, the song “disappears” and “devolves back into other songs,” and even other genres (“a cool jazz moment … that’s no longer part of a rock ’n‘ roll show in Denver”). After they “lose the beat, the song slips, they have trouble finding their way back into the verses.” When Morrison returns, “there’s a song to take back and rebuild,” except that this time even Morrison can’t seem to save it, it isn’t there for him, “the solos the musicians have just found and lost have left the song without a body, just head, hands, and feet, spinning, flailing.” Now it’s drummer John Densmore’s chance to set things right as he delivers a “pattern of five strokes that says Time’s up. Put up or shut up [Marcus’s italics].” But they still aren’t there. Densmore keeps bringing them to the brink of an ending, “the certainty that the song will break through,” but it’s not happening. Marcus imagines Morrison “down on his knees, pushing the song through a wall.” Now “desperation builds on itself,” Manzarek is “shouting from behind, all excitement,” but “excitement wrapped in fright … that the wall may hold.” At this point you realize how much Marcus himself has invested in the song, he’s there with the Doors, in the moment, as the thing “finally crashes to a close,” and “they’re still pushing, the wall is still holding. The song is over but the story it’s telling is still going on. You can’t hear it but you can feel it on your skin.” Writing inside the music without straying into mere nomenclature, Marcus pushes his story of the song through the wall, at the same time echoing the Doors’ primal statement, set forth in the chorus of the opening track on their first album, “Break on through to the other side.” Marcus’s vision of art that “can as easily meander in circles as cross borders and leap gaps” describes what I heard when listening to the first two albums for the first time in decades the other day. At his best, Krieger puts everything into play, Morrison’s fascinating chaos, the exotic sidetrips, the flights, the stumbles and falls, pushing, circling, rounding, breaking through, desperation admitted, celebrated and mastered, the haunting thread found and lost and found again. It’s not just exotica that the guitarist and his arsenal of effects are contributing when he and the Doors are at their early best: he’s telling their story. Morrison may write the poetry, but Krieger plays it. There’s more Poe than poetry in Ray Manzarek’s organ, as Marcus expresses it. Like the opening into “Strange Days,” the title track of the second album, which is “the spookiest moment of the Doors’ career, and one of the most alluring.” In 1967 “it would have made people think of The Twilight Zone,” today it would be “David Lynch’s Lost Highway.” (In Oliver Stone’s 1991 film, The Doors, Manzarek is played by David Lynch hero Kyle Mac-Lachlan, aka Zen detective Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks.) In his chapter on the first album’s eerie “End of the Night,” Marcus suggests that Manzarek’s playing calls forth “memories of late night TV creep-show movie marathons, or even more directly the music from early network suspense programs,” until it transcends those memories and “takes you somewhere else.” Nice and Smooth My own “lifetime” with the Doors was packed into the first two albums, both released in 1967. The third album, Waiting for the Sun (1968), was a huge disappointment. I went looking for highlights from the later LPs, thanks to Marcus’s chapter on “L.A. Woman,” where the mystery guest is Thomas Pynchon. In “Roadhouse Blues,” Marcus invites in, among others, Louise Brooks and Eric Ambler, along with Charles Manson, Aleister Crowley, and L. Ron Hubbard. While many found the dark side of the sixties in the music of the Doors, I was one of the people Marcus may be referring to in a Publishers Weekly interview when he speaks of the need to believe in the “great myth” of the 1960s “with the notion of possibility at its heart,” a notion the Doors “still represent.” These people “either bring a yearning for that sense of possibility, or perhaps a corrupted memory of that sense of possibility.” My yearning took the form of blissing out and dancing myself silly to “I Looked at You” and “Take It As It Comes” or singing along with Morrison on “People Are Strange” and “You’re Lost, Little Girl” from Strange Days. “Nice and smooth,” said my mother when I put the headphones on her ears and played the latter song. Smooth is right. Listen to the blending of Krieger’s playing and Morrison’s ghostly vocal. “Little Girl” isn’t mentioned in Marcus’s book, but it’s a joy to sing along with, as is its counterpart on the same album, “Unhappy Girl.” It may sound odd, given all the dark doomy Doors imagery and Morrison’s surly in-person presence, but singing along with Jim on these songs is like singing along with Sinatra. The two “girl” songs may seem emotionally lightweight compared to “Strange Days,” “Moonlight Drive,” “My Eyes Have Seen You,” and “When the Music’s Over” (“We want the world and we want it – NOW”), but they’re crucial to the mood and mystery of the second album and nicely complement the infectiously melodic joyride of “People Are Strange.” The other Doors make haunting music, but for sheer strangeness, they’re not in the same league with their leader, the human storm in the title of John Densmore’s memoir Riders On the Storm. For instance, Ray Manzarek’s account of the time they were on their way to a concert. While the other three Doors sat in the back of the limo eating ice cream cones, Morrison was swilling Scotch straight from the bottle. In an online video, Morrison’s sister Anne recalls his request for a high school graduation present: “He asked my parents for the complete works of Nietzsche.” Up Close In Person In the annals of Jim Morrison meltdowns, exposures, and arrests, the Doors concert of October 20, 1967, at the University of Michigan ranks near the top. Keep in mind that at this time few in the audience knew who Morrison was, even though “Light My Fire” had been one of the summer’s biggest hits. Tickets were $3, everyone was standing, and we were up front near the steps that led to the stage, where the Doors were stalling as they waited for their lead singer. He was in fact nearby, a few yards in front of us. No groupies were rushing him, no hip coeds. He didn’t seem particularly intimidating: we saw no charisma, no menace, no poetry, just a strung-out-looking guy dressed in black leather slumped over a railing. The crowd was restless; there was some booing. I was ready to urge him on – he was close enough to hear me – and when he looked up, glowering, then smiling, slyly, the posturing drunk was suddenly radiating charisma, menace, and poetry. I have an image of him taking the steps in one bound, crossing the stage, grabbing the mike, and coiling himself around the mike stand. As the band played “Soul Kitchen,” Morrison wasn’t singing. He was cursing the audience. F-words galore. Leaning over the edge of the stage, he crooned fabulous obscenities, insulting one and all, goading them, leading a chorus of boos and hisses until the campus police stopped the show before he’d sung a note. In the interval, as the Big Ten homecoming-dance portion of the audience left the building, I found myself standing next to Robby Krieger, who had been shooed off the stage with the others. I apologized for the crowd, an odd thing to do, given the fact that Morrison had provoked them. But I was still under the spell of Strange Days, which had just come out, and I was sure that the Doors were the most exciting group in America. And when they finally climbed back on the stage, what a set they played for the faithful who had come not to dance but to listen. Greil Marcus is on a roll, three books in one year. With Bob Dylan and Van Morrison, he’s meditating on giants. With the Doors, it’s all about the group, the story of those songs, and of a period of time (1966-1971) end-marked by Jim Morrison’s death in Paris July 3, 1971. Also out this month is The Doors FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock by Rich Weidman (Backbeat $13.59). |