|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 47

|

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

|

|

|

Subscribe to our newsletter |

|

Vol. LXV, No. 47

|

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

|

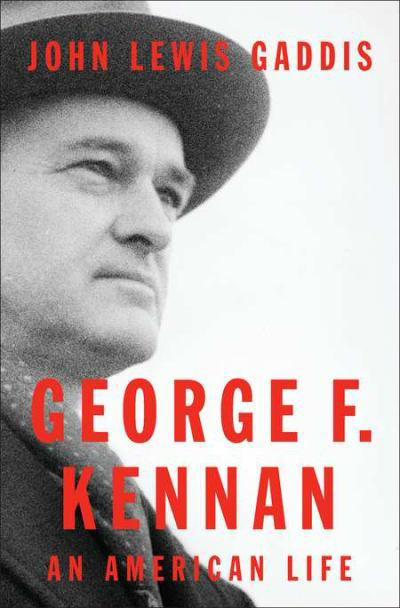

Remembering George F. Kennan, the Elder Statesman of Hodge RoadStuart MitchnerBefore I’d read past page five of John Lewis Gaddis’s George F. Kennan: An American Life (The Penguin Press $39.95), I knew I wouldn’t be able to write about the book objectively. Even the dedication — “In memory of Annelise Sørensen Kennan” — will have emotional overtones for anyone who had more than a casual fondness for George and Annelise Kennan. In fact, Annelise comes to life a few paragraphs later when after referring to his 23-year-long relationship with his subject (it “could not have been better”), Gaddis writes that he and Kennan “originally thought of the book as more political than personal,” until Annelise “strongly objected,” reminding them that her husband’s writings “were full of gloom and doom” and that Gaddis “must get to know him well enough to see that he was not always this way.” Gaddis goes on to tell how “the stabilizing role” Annelise played in her husband’s life became clear to him one evening in Princeton in 1983: “The Kennans were just back from Norway, and when I asked how it had been, George started complaining about dissolute youth hanging around the docks. Annelise put an end to that: ‘George, you’re always worrying about docks!’ All docks everywhere had dissolute youth. That, along with tying up boats, was what they were for. And then, turning to me: ‘He worries too much about the docks.’ “ Thus: “Annelise had her way with this book, and that’s why I have dedicated it to her memory.” A Backyard View At the time of the dock exchange, I was living in the garage apartment behind the Kennan home on Hodge Road with my wife and seven-year-old son. Although the biographer, a history professor at Yale, had been granted “unrestricted access” to Kennan, “his papers, and his mostly handwritten diaries,” he saw his subject “about once a year for a quarter of a century.” Except for their summers in Norway, we saw George Kennan almost daily for six years; we saw him in his bathrobe tossing stones at marauding squirrels, shoveling snow, chopping wood for the stove in his tower study, climbing up a scarily tall ladder to clean the gutters, and we saw him sitting on the bench in front of our little house as my son opened his hand to display the creature he’d found somewhere on the Kennan property. Asked if he knew what it was, the elder statesman of Hodge Road not only identified it but said a few mild, earnest, soft-spoken words about the humble skink and its place in the universe. Qualities of Wonder “The fact is that one moves through life like someone moving with a lantern in a dark woods.” So begins the second paragraph of George Kennan’s Memoirs: 1925-1950. As he develops the metaphor, the lantern illuminates “a bit of the path ahead” and “a bit of the path behind” while “the darkness follows hard on one’s footsteps, and envelops our trail as one proceeds. Were one to be able, as one never is, to retrace the steps by daylight, one would find that the terrain traversed bears, in reality, little relationship to what imagination and memory had pictured.” I read that passage shortly after meeting George Kennan for the first time. I was examining the Memoirs for clues as to what sort of a person we were going to be living behind. As I read I was disarmed by the reference to “our” trail. The shift from “one” to “our” brought me aboard. Reading on, I felt myself bonding with the author, our august and austere landlord, who, however, “habitually read special meanings into things, scenes, and places — qualities of wonder, beauty, promise, or horror — for which there was no external evidence visible, or plausible, to others.” His world “was peopled with mysteries, seductive hints, vague menaces, ‘intimations of immortality.’” I went to the living room window and looked across the park-like expanse of the back yard to the small lighted window in the tower of the Kennan house wondering what he was working on up there. Five months later the news came over the radio as I was washing the dishes. George Kennan had won the Einstein Peace Prize. Along with all the rest — historian and statesman, architect of containment, former ambassador to the Soviet Union, memoirist quoting Wordsworth, poet and mystic — our landlord was being honored for attempting to save the world. Visions and Dreams Any number of other reviews will tell you all you need to know about how Gaddis portrays George Kennan’s unique career in the Foreign Service. I was looking for something more personal, something relevant to what I felt that October night in 1980 staring out the window at the lighted tower. I wanted intimate insights from the “stack of loose-leaf binders” containing Kennan’s diaries that Gaddis was allowed to take away with him after one of his last visits to 146 Hodge Road. And then there was that “single, smaller volume” of which Kennan said, “‘I guess you wouldn’t be interested in this.’” Gaddis asked what it was. “‘Oh, just my dream diary.’” Once again, Annelise to the rescue: “‘Take it too,’” she insisted. Clearly, Annelise trusted Gaddis to live up to this “extraordinary expression of confidence.” How wisely and tastefully he does so becomes immediately apparent and explains why I found myself emotionally involved from the first pages of the book. Beginning with the death of Kennan’s mother only two months after his birth in Milwaukee on February 16, 1904, Gaddis presents five passages from the diaries that suggest the lasting impact of that loss (“the rending of a relationship so brief that it could not even exist in memory”). In the Memoirs, after admitting to having been “scarred for life,” Kennan moves on through the metaphorical “dark woods” because he was, as Gaddis puts it, “not then prepared to reveal where the evidence lay, in the realm of visions and dreams.” Gaddis incorporates each passage into the third person. In the first, from 1931, a “young diplomat” realizes “that Mother is far away and that no one is ever going to understand you and that it is not even very important whether anyone ever does.” In 1942 “an older Foreign Service officer” interned in Nazi Germany, “married now and a father,” wonders if his children “would remember him were he not to return” and wishes he “could have had at least one conversation” with his mother. In 1959 “a middle-aged historian … dreams for the first time of meeting his mother” who “is plainly preoccupied with something else” and “accepts with politeness” his “instantaneous gesture of recognition and joy and tenderness.” In 1984 “an aging brother, now eighty,” speaks to his sisters of “the desperation our mother must have felt as she faced death with the realization that she was being torn away relentlessly from four small children and abandoning them to a wildly uncertain future.” Finally, and most movingly, the passage from June 1999: “A distinguished elder statesman, at ninety-five failing physically but fully in command mentally, suddenly sheds tears as he recalls Anton Chekhov’s haunting story ‘The Steppe,’ about a boy of nine traveling with a group of peasants across a vast Russian landscape. The boy misses his mother, ‘understanding neither where he was going nor why,’ trying to grasp the meaning of stars at night, only to find that they ‘oppress your spirits with their silence,’ hinting at ‘that solitariness awaiting us all in the grave, and life’s essence seems to be despair and horror.’” Lenin’s Widow By December 1987, we had moved from the garage apartment behind the Kennans into a home of our own and George and Annelise were coming to dinner. I don’t remember much of what was said. George quoted a Russian proverb as they entered the house, the first we’d ever owned, and there was some talk about a recent event where he’d been hugged by Gorbachev. That’s all I remember. Gaddis tells the whole story. Invited to the Soviet embassy reception on the occasion of Gorbachev’s first visit to the United States, George was standing on the fringes “until Annelise took charge. ‘For goodness sake, go up and greet people.’” And so he does, pushing past Kissinger, McNamara, McGeorge Bundy, and John Kenneth Galbraith, not to mention Billy Graham, Paul Newman, Joyce Carol Oates, Norman Mailer, Robert De Niro, and John Denver. Gorbachev recognizes Kennan, opens his arms and embraces him. “It was not what Kennan had expected from the first successor to Stalin he had ever met.” Meanwhile — “Seated at Kennan’s table while Gorbachev spoke was [in Kennan’s words] ‘a lady of most striking appearance, who chain-smoked Danish cigars and appeared to be rather bored with the whole performance …. I was later told that I should have recognized her — as widow of a famous rock star.’ His name, strangely, was something like ‘Lenin.’” That’s all. No comment from Gaddis. He lets the bizarre scene speak for itself. The Soviet social secretary or whoever concocted the extraordinary guest list had seated the Kennans at the same table with Yoko Ono. A Bit of Life In a January 1982 letter to his cousin Charlie James, George Kennan writes that “there is a bit of life still to be lived — a bit to be seen of the tragic beauty and poetry of this world — a bit, in short, to be witnessed, perceived, and recorded.” Fortunately for the world, he had 20 more years to live and six more books to write. |