|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 40

|

|

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

|

|

|

Vol. LXII, No. 40

|

|

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

|

|

Every now and then as I’m sorting through the stock for the Friends of the Library Book Sale, I’ll find myself imagining the story behind a particular donation. Beginning with the look and feel of the books, the storyline develops from the range of subjects, traces of the owner’s identity in the form of elaborate inscriptions, or endpapers bearing person and place names and dates, or from clues such as makeshift bookmarks and the family photos that sometimes turn up between the covers. The plot thickens when you find underlinings and marginal notes, although these markings usually devalue a book to the point where you hesitate to put it out for sale.

One exception to this rule and one of the most interesting donation back stories ever concerns the subject of this column, Anne Martindell, who died at the age of 93 in June. As I was going through the 14 hefty boxes of books from her library last week, I noticed that several volumes about the tumultuous events of that wild political year, 1968, contained penciled annotations suggesting her involvement in the presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy and the Democratic convention. Intrigued, I took home her copy of Charles Kaiser’s 1968 in America: Music, Politics, Chaos, Counterculture, and the Shaping of a Generation. Although I had not then read Martindell’s recently published memoir, Never Too Late (Boxed Books $29.95), the annotations I found in her copy of 1968 suggested that she’d used the book almost 40 years later in writing her own account of that period. Marginal notations appear in reference to the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (“I was there”), other major war protests (“I was in NY and Washington”). In the margin next to the words of a co-worker in the McCarthy campaign quoted as saying that she realized the “world was in the hands of people like me,” Martindell noted, “my reaction to being elected,” a reference to her election to the state senate in New Jersey some five years later.

The more I saw of the Martindell donation, the more I began to think it would be interesting to display these varied and suggestive pieces of an extraordinary life as a self-contained entity, something that worked out nicely with last year’s sale featuring books from the library of the late Borough mayor Joseph O’Neill. In addition to wanting to know the story behind those marginal notes (as well as the underlinings in a biography of New Zealand painter Toss Woollaston), I was intrigued by the range of interests covered in Martindell’s reading matter — politics and New Zealand, McCarthy and McGovern, Camus and Jefferson, and Robert Lowell. So I went to the new non-fiction shelves at the library, found her memoir, checked it out, and satisfied my curiosity.

Facing Challenges

What a contrast Never Too Late is to the oral history of Bella Abzug I was reading and reviewing a few weeks ago. On one hand you have a political dynamo from the Bronx shaking up Washington and the culture at large; on the other, the dutiful, well-born (you could say Park Avenue) daughter of a remote mother and a tyrannical father. Because of the adversity she had to deal with at home, her struggle and her achievement seem even more remarkable than Abzug’s. Simply to survive so cold and brutal an upbringing would be a challenge in itself. It’s the “poor little rich girl” story with a vengeance; in childhood her “principal crime was reading,” and for that she was spanked with a hair brush. After a difficult boarding school experience, she finally begins to find herself in her first year of college (at Smith), only to be pulled out by her father and for all purposes forced into marriage at 19 (at Trinity Church in Princeton: “I felt like an actress in a play — a very bad play”). You’re feeling for her, from the first scene where her beloved nanny takes her in for her daily ritual “visit” with “Mummy” to the triumphant completion of her education at Smith at age

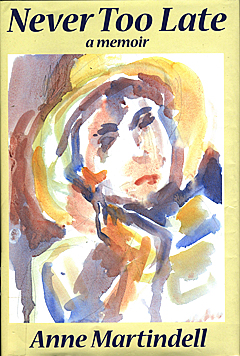

87. And you’re cheering her on through 1968, the year that changed her life, sending her into politics and the career that peaked when President Jimmy Carter named her ambassador to New Zealand. Probably the biggest cheer you give comes when she finally finds love, in her 60s, with that same Toss Woollaston whose underlined biography had you wondering and whose charming, semi-abstract portrait of her is reproduced on the cover of Never Too Late.

The events of 1968 gave Martindell passion and commitment to a cause, and her defining woman’s-rights moment is the heroic equal to any of Bella Abzug’s. Soon after she’s tapped to become vice-chairman of the Democratic party in New Jersey, she discovers that there is “a stark divide between the male and female roles in the party.” Women are expected to “pour coffee and stuff the envelopes and be happy with little pats on the head for the good work.” Refusing to accept what she considers to be “a female ghetto,” she speaks to women’s groups around the state, trying to “stir up” the envelope stuffers (“What did the women get, beyond perhaps a focus for their social lives?”). When she learns that the state chairman, Sal Bontempo, has called a meeting of the party “Big Bulls,” she tells him she wants to be there. Instead of backing off when she’s told “the boys don’t want any women there,” she proceeds to crash the party. “I’ve studied the rules,” she tells the all-male assemblage, “and I’ve come to represent the nearly 600 Democratic committee women.” After a “dead silence,” she’s gently told that “rough language” is sometimes used (“We wouldn’t want to offend you”). Her I-don’t-give-an-“expletive” reply settles the question and makes the next day’s news. That sweet moment of staring down the “Big Bulls” and becoming overnight “a bona fide political figure in New Jersey” was the prelude to her eventual run for the state senate.

The Anne Martindell contribution to this week’s book sale may be scattered to the winds once the crowd at the noon Friday preview plows through the tables, but when and if you find a book on New Zealand, or McGovern, or McCarthy, or any of the other highlights of her fascinating life, chances are it once belonged to her, and now to the community, thanks to the donation given by her four children, Marjory, George, David, and Roger.