|

|

Vol. LXIII, No. 35

|

|

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

|

|

Really to read Pynchon properly you would have to be astonishingly learned not only about literature but about a vast number of other subjects belonging to the disciplines and to popular culture, learned to the point where learning is almost a sensuous pleasure, something to play around with, to feel totally relaxed about, so that you can take in stride every dizzying transition from one allusive mode to another.Richard Poirier

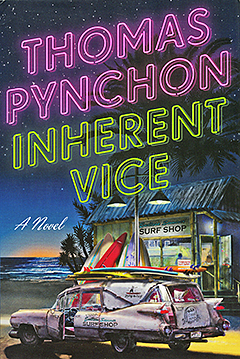

I’d just started Thomas Pynchon’s latest creation, Inherent Vice (Penguin $27.95) when a copy of Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Vintage $14.95) came my way. Though I rarely read thrillers, I put Pynchon aside for this one because of the title character. As soon as that anorexic hacker Lisbeth Salander entered the story, I couldn’t stop reading. Two days after she held out her skinny hand and pulled me in, I was done, and I’d have gone right on to The Girl Who Played with Fire except for the Pynchon, which has taken me three weeks to get through.

I have to scratch my head when I read reviews describing Inherent Vice as “a beach read,” a “page-turner,” a “breezy work of genre fiction,” an “amusing snapshot.” This convoluted jeu de cannibas is less a page-turner than a mind-twister, and just as marijuana can make a minute feel like an hour, Pynchon can make his novel’s 369 pages feel like 800. The California setting and counterculture ambience recall his most accessible novel, Vineland (1990), but that one’s a lark by comparison. To properly apprehend Inherent Vice you have to access, inhabit, and more or less disappear into the pot-befogged brain of its private eye protagonist, Larry “Doc” Sportello. As you trace your way through the holes and fissures, nooks and crannies of narrative, it’s like trying to make sense of fragments laid out on a sheet of paper resembling the one Doc inserts in his Olivetti that “appeared to have been used repeatedly for some strange compulsive origami.” Things begin to make sense only when you realize that Pynchon is creating his own stoned aesthetic; he wants to disorient you.

Over and over again Pynchon replicates in the mad matrix of his plot the memory lapses Doc is constantly subject to, as when after doing an impersonation of Edward G. Robinson, he asks, “Oh. Was … I doing that out loud?” Or when after eating a meal, he asks, “What happened to our food man, it’s taking them an awful long time to bring it.” Or: “Being the continuation of a long story Doc had forgotten, or maybe missed, the beginning of.” All through the book it’s what and how and who. What story? Beginning where? Told by whom? The question mark rules, punctuating even seemingly simple declarative lines of dialogue.

Missing Something

After suggesting that Inherent Vice “does not appear to be a Pynchonian palimpsest of semi-obscure allusions,” Louis Menand is closer to the truth when he admits in his New Yorker review, “I could be missing something, of course. (I could be missing everything.)” In case you think that you’re not dealing with a “Pynchonian palimpsest,” just visit Inherent Vice’s wikipedia-gone-wild website’s page-by-page variorum.

Menand’s admission could have come from the lips of Doc Sportello himself, a man who can’t get through a minute of the day without thinking he’s “missing something” or forgetting having done something he just did. Imagine a caper involving all the usual LA-noirish elements (real estate swindles, kidnapping, murder) being investigated by a detective whose thought process is described in terms of things “deliberately lost and found again … and there was something now scratching like a rogue chicken at the fringes of the unkempt barnyard that was Doc’s brain, but he couldn’t quite locate it, let alone account for the critter when evening rolled around.” Exactly the paradigm of Inherent Vice: you read a reference to a place, person, incident, you lose it (but not deliberately), then you find it (if you look hard enough).

It isn’t just that Pynchon’s doing a number on Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe here. Doc can also be read as a travesty of Sherlock Holmes (if not on the same low-comedy level as the Mad Comics version); instead of the cocaine-energized mastermind you have a pot head who hallucinates clues (“It helps to smoke a lot of weed and do acid on and off”) and is a good shot when it counts: “He waited till he saw a dense patch of moving shadow, sighted it in, and fired, rolling away immediately, and the figure dropped like an acid tab into the mouth of Time.” Perfect. You begin in Chandler country and end up on Gummo Marx Way in the Pynchon District, where things go round and round “but never end up in exactly the same place,” to quote Bigfoot Bjornsen, Doc’s LAPD nemesis/sidekick (the Lestrade to his Holmes, the Claude Rains to his Bogart, the Abbott to his Costello). “Like a record on a turntable,” according to Bigfoot, “all it takes is one groove’s difference and the universe can be on into a whole ’nother song.”

In a book where some radio station’s constantly playing period music (amazon.com offers a downloadable playlist apparently provided by the author), the reference to a record fits right in. You could also put together a DVD anthology of the quotes from Hollywood, but don’t go looking for Burke Stodger in .45-Caliber-Kissoff.

When you come right down to it, Doc is less a character than a whole twilight-of-the-sixties state of mind disguised as a private eye. With Lisbeth Salander, you know how she talks, thinks, looks, sounds, and smells. With Doc, it’s more subtle, like the “glittering mosaic of doubt” the first paragraph of Chapter 20 compares to the marine insurance term that gives the book its title. “Inherent vice” is “stuff marine policies don’t like to cover.” Like a cargo of eggs that might break. Or, as Doc suggests, “like original sin.” Or, from the same paragraph, like a private eye “who got out his lens and gazed into each image till one by one they began to float apart into little blobs of color.” It’s no surprise that a book as compellingly cryptic as Inherent Vice pictures this derangement as both “a kind of limit” and “a gateway to the past.” One thing for sure, if you want to smell Doc, all you have to do is light a joint and remember how it was way back in those innocent days of yore when the odor all by itself was enough to get you high.

From the concept called Oedipa Maas in The Crying of Lot 49 to the essence of delight in Vice called Trillium Fortnight, Pynchon’s characters may not exert the same human fascination as Lisbeth Salander, but one of this novelist’s favorite fixations involves exploring the no-man’s land between character and concept, which is why he writes literature and Stieg Larsson writes page-turners. Fog in Larsson is just fog, a piece of functional atmosphere. In Pynchon it’s the holy grail of metaphor. You have fog as fog, fog as atmosphere, fog as the element of the mystery and all its oddities and obfuscations, or as the smoke of a drugged-out narrative the reader is moving carefully through, or, most powerfully, at the end, fog as “a patch of blindness” being traversed by a convoy of cars “like a caravan in a desert of perception.” The fog-eloquent concluding paragraphs of Inherent Vice are worth more than a thousand page-turners, even ones as accomplished as The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Also worth a mention according to what separates the inhaling of a Pynchon joint-in-prose from a page turner is that it’s often laugh-out-loud funny. At its weakest, Vice’s humor makes you grimace and roll your eyes; at its best the humor pulls you in — as happens early on with the description of Doc’s place of employment where the sign reads LSD INVESTIGATIONS (the LSD standing for Location. Surveillance. Detection), beneath which is “a rendering of a giant bloodshot eyeball in the psychedelic favorites green and magenta, the detailing of whose literally thousands of frenzied capillaries had been subcontracted out to a commune of speed freaks who had long since migrated up to Sonoma.”

As for Doc’s office, it consists of “a pair of high-backed banquettes covered in padded fuchsia plastic, facing each other across a Formica table in a pleasant tropical green. This was in fact a modular coffee-shop booth, which Doc had scavenged from a renovation in Hawthorne.”

And put in place by Thomas Pynchon, who has been scavenging literature out of the waste of culture and history for almost 50 years now.

Poirier’s Rainbow

Just as it was impossible to write about the Beatles and Lester Young in the shadow of Richard Poirier’s August 15 death without mentioning the impact of his work, the same is even truer in reference to Pynchon. Poirier was arguably the first literary authority to write about and teach Thomas Pynchon. It was Poirier who greeted Pynchon’s debut V (1963) in the New York Review of Books, declaring that it earned the author “the right to be called one of the best [novelists] we have now.” Three years later his New York Times review of The Crying of Lot 49 helped put Pynchon on the literary map, much as his eloquent, in-depth reading of Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) in the Saturday Review created the excitement that helped make Pynchon’s masterpiece a best-seller and eventual National Book Award winner.

It would be hard to imagine a more inspiring teacher-author pairing than Poirier and Pynchon, a combination I was fortunate enough to see in action at Rutgers in Poirier’s course on Recent American Literature. Any student who also happened to be exploring Joyce or Spenser in Introduction to Graduate Study in the late sixties knows that Poirier’s classes were usually no less brilliantly and deviously plotted than The Crying of Lot 49. Each session was a communal quest for the luminous resolution that never quite completely emerged from a classroom work-in-progress that could be both fascinating and exhausting. Pynchon provides a fitting analogy to that experience at the end of Inherent Vice, if you can imagine Poirier as the larger guiding light in that fogbound convoy “of unknown size, each car keeping the one ahead in taillight range, like a caravan in a desert of perception, gathered awhile for safety in getting across a patch of blindness.”

The passage quoted in the epigraph is from Richard Poirier’s essay “The Importance of Thomas Pynchon,” which can be found in the groundbreaking anthology edited by his colleagues George Levine and David Leverenz, Mindful Pleasures: Essays on Thomas Pynchon (Little, Brown 1976), available at the Princeton Public Library.