|

|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 36

|

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

|

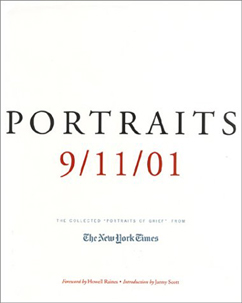

“Human and Heroic New York” — Ten Years Past September 11Stuart MitchnerFlying out of Newark on a brilliantly clear night in March 2002, we saw a vision in the sky above Manhattan. The spectacle of two phantom towers soaring beyond any mortal architect’s wildest dreams had people going “Oooh” and “Ahhh!” These happy sounds were followed by a falling off, a shared sigh as people remembered what was signified by those two shafts of blue light. If you felt love for New York before September 11, your love overwhelmed you when Manhattan was the emotional epicenter, the aching heart of a stricken nation. New York became America’s city that fall. When the baseball season started up again a week later, ballparks all around the country were handing out “I Love NY” buttons, and there were banners reading “NYC, USA, We Are Family.” Even in Boston they were playing “New York, New York” on the Fenway Park organ. In the city, when passing strangers met your gaze, you connected, as if you were sharing the same loss. Every firehouse had a shrine. Suddenly cops were heroes and firemen were holy warriors. The emotional climate of the city reminded me of how it was during the 1996 World Series when Joe Torre was the man of the hour. In the fall of 2001, it was Torre who once again seemed closer than any other public figure to the heart of the city we loved. The Greatest Poem In his introduction to the New York Times’ Portraits: 9/11/01 (Times Books/Holt 2002), Howell Raines picks a line from Walt Whitman to describe the 1,910 stories it took 143 Times reporters to research and write: “These lives bundled together so randomly into a union of loving memory … remind us of what Walt Whitman knew: ‘The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem.’” Whitman made that statement in an introduction of his own, to the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855). Twenty-three years later, in a chapter from Specimen Days in America titled “Human and Heroic New York,” he reports his findings after three weeks walking the streets, riding the ferry boats, horse-cars, and crowded excursion steamers, exploring Wall and Nassau Streets, the “democratic Bowery” and places of amusement, observing “endless humanity in all phases …. No need to specify minutely — enough to say that (making allowances for the shadows and side-streaks of a million-headed city), the brief total of the impressions, the human qualities” are “comforting, even heroic, beyond statement.” Looking at the faces and reading the stories in what Raines calls 9/11’s “democracy of death,” you can’t help but think of Whitman’s assessments of “alertness,” “clear eyes that look straight at you, a singular combination of reticence and self-possession … surely beyond anywhere else upon earth.” For Whitman, his “daily contact and rapport” with the city’s “myriad people” provided “the best, most effective medicine my soul has yet partaken.” Falling If you want to revisit the nightmare of 9/11, you can find it in books like 102 Minutes (Times Books 2005) or Never Forget: An Oral History of September 11, 2001 (Harper Collins 2002), which is still disturbing to read ten years later. If anything, these in-the-horror-of-the-moment accounts are more harrowing in their searing intimacy than the on-the-scene videos that are sure to be all over TV next week. For instance, there’s the rookie paramedic who actually seemed to think he could catch the people who were jumping or falling from the north tower. His superior, who had seen “two separate firemen” killed by falling bodies, had to hold onto him, “almost had to knock him to the ground,” telling him, “‘You can’t. They’re going to kill you.’” That was on page 33. I stopped on page 54 after reading the experience of the 29-year-old trading company executive who had been on the 85th floor of 1 World Trade Center when he saw “the plane coming into the building.” He says he is “still waiting for something else to happen.” He thinks that if something else does happen, “it will happen in New York.” I wonder how he feels as the 10th anniversary approaches. A Very Special Fireman You may not find Whitman’s medicine for the soul in the faces and stories of the victims collected in Portraits but as you view them you’ll most likely share with Howell Raines an “awareness of the subtle nobility of everyday existence” and “of the unforced dedication with which our fellow citizens go about their duties as parents, life partners, employers or employees.” And in case you find yourself generalizing (“all firemen are alike”), there are startling exceptions such as first responder Vincent Kane from Engine Company 22 who lived on the Upper East Side, spent hours in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, went to performances of the New York Philharmonic, regularly patrolled the firehouse trash bins for recyclables, became a vegetarian, and loved to play music by the Grateful Dead or the Beatles on his guitar, which he kept in his locker at the firehouse. “His neighbors on East 80th Street … listened for the music wafting softly from his apartment late at night.” It’s in entries like that one that the Times’ American poem takes hold. Portraits Redrawn “Writing the book also gave her a way to protect Eddie. ‘It felt good to stick him in a book; he’s safe in there,’ she said. In her book, he’s always 31 years old.” Alissa Torres is talking about her husband Eddie, who died on 9/11. Her account of what she’s done in the ten years since is available in the New York Times’ interactive “Portraits of Grief” site, where you can now also read updates from the victims’ friends, families, and loved ones in “Portraits Redrawn.” When you enter the site, you find different groupings of faces and stories featured upfront while updated material is in the sidebar. Otherwise you can search by letter. The person I picked at random today, September 5, is Marina Gertsberg, who was four when her father chose not to serve with the Soviet forces in Afghanistan and took his family from the Ukraine to the Howard Beach section of Queens, where Marina went to the Mark Twain School for the Gifted and Talented, Stuyvesant High School, and the State University of New York at Binghamton. A week before 9/11 she joined Cantor Fitzgerald as a junior manager. Three days before her death at 25 she was maid of honor at a friend’s wedding in Brooklyn, “walking down the aisle in a purple gown that set off her blue eyes,” according to her mother. “She was like a queen.” Princeton’s Modest Memorial One of the most serene 9/11 memorials is on the Princeton University campus where East Pyne Hall connects with Chancellor Green, just east of Nassau Hall. The effect is that of an intimate outdoor chapel. Jon Hlafter’s design has 13 gold stars circling a paved walkway within a garden that displays the names and class years of the Princeton alumni killed in the attack. At the entrance to the garden is a bronze Remembrance Bell created by Toshiko Takaezu, a visual arts professor who died this past March 9. The memorial was dedicated on a drizzling Saturday, September 13, 2003, by University President Shirley Tilghman. While other area residents were lost on September 11 (notably Cranbury’s Todd Beamer, one of the heroes of Flight 93), I looked up the online sketches of the 11 undergraduates and two graduate students honored in the memorial garden and found a few words about each that suggest some of the “human qualities” documented in Portraits: 9/11/01. The 13 Princetonians killed in the September 11 attacks were: undergraduate alumni Robert Cruikshank ’58 (“You could trust him. He was a rock to everyone”); Robert Deraney ’80 (“He set an elegant table with china and silver for 35 and ended evenings by playing the piano”); Christopher Ingrassia ’95 (“What stood out about him was the deep kindness he poured out on friends and strangers alike”); Karen Klitzman ’84 (“Living in a house wedged between a pig farm and a brothel, she escaped to Hong Kong on the weekends”); Catherine MacRae ’00 (“She was beautiful and funny and charmingly self-deprecating and talked on the phone to her mother at least three times a day”); Charles McCrann ’68 (“Charlie did two important things in 1979: he married his wife, Michelle, and he produced, directed, and starred in the horror film Toxic Zombies”); Robert McIlvaine ’97 (“The guy devoured books: the fiction of Toni Morrison, essays by Cornel West”); Christopher Mello ’98 (“a poet, a film buff, and an artist); John Schroeder ’92 (“One Halloween he was Paul Stanley of the rock band Kiss; another time he made an Elvis costume and found many other excuses to wear it”); Jeffrey Wiener ’90 (“Jeffrey and Heidi Wiener became engaged at F.A.O. Schwarz, in front of the big clock”); Martin Wohlforth ’76 (“I have a picture of him holding our daughter for the first time in the hospital with a mask on”); and graduate alumni William Caswell ’75 (“ His technical and management skills were held in the highest esteem by his colleagues and were officially recognized by major Navy awards and commendations”); and Joshua Rosenthal ’81 (“He was not a daredevil, but he did have a childlike adventurous streak”). Let Walt Whitman sum things up, from his introduction to the 1855 Leaves of Grass: “Men and women and the earth and all upon it are simply to be taken as they are, and the investigation of their past and present and future shall be unintermitted and shall be done with perfect candor.” The quote for William Caswell is from a memorial note in the Princeton Alumni Weekly. The New York Times site is www.nytimes.com/interactive/us/sept-11-reckoning/portraits-of-grief.html. |