|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 37

|

|

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

|

|

|

Vol. LXI, No. 37

|

|

Wednesday, September 12, 2007

|

|

The quirkiest prison movie ever made may be Up the River, directed by John Ford and released in 1930. This is a prison where the warden’s little girl plays with the inmates and cheers on their baseball team and where prisoners stage minstrel shows and perform in drag. Aside from the quirkiness, the outstanding feature of the movie is the presence of a charmingly boisterous newcomer named Spencer Tracy, a force of nature compared to the stiff, leading-man types who gummed up the works in so many early sound films.

In fact, one of those charmless romantic leads plays a character named Steve in Up the River. Slightly built, borderline effeminate, with a weak voice, he’s a bit funny-looking, sweet but sappy, a circa-1930s nerd who at one point actually “goes home to mama.” He’s a step above the worst of the hapless leading men of the early talkies only because he delivers his lines with relative ease and lacks the usual pretty-boy good looks. If you told movie executives coming out of a showing of Up the River that the little guy with the laughable first name playing Steve would one day be an international icon, the ultimate existential movie hero, the tough-guy incarnate voted “the greatest male screen legend” by the American Film Institute, you would be met with incredulous laughter.

A mere six years later, after bottoming out in Hollywood and slinking home to New York and the theatre, that same clean-cut lad with the unfortunate first name is back on the screen as an unshaven, tightly wound piece of pure menace named Duke Mantee. Unshaven, with eyes in which no light shines, haunted, harrowed, relentless, talking in a demented monotone, Humphrey Bogart doesn’t merely act the part; he’s apparently possessed by it, locked into it, you might even say straitjacketed in it. This may have been, as is generally accepted, his “breakthrough role,” but the killer who seems to be turning to stone before our eyes in The Petrified Forest is not the Bogart who was proclaimed the greatest of male screen legends in his centenary year, 1999. At his best, Bogart is the opposite of petrified. In The Maltese Falcon his Sam Spade is a study in tics and grimaces. Watch the way he’s always tugging at his ear as Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep. In The African Queen his Academy-Awardwinning performance is one of the most complete, vividly worked out creations ever filmed, full of humor, character, and sheer physical energy; even his stomach gets into the act by growling at an inopportune moment.

According to the commentary and special features on the DVD of The Petrified Forest, Warners wanted to use top-billed tough guys like Edward G. Robinson or James Cagney for the part of Duke Mantee. The best they could do for Bogart was to let him play one of the killer’s henchmen. Leslie Howard, who co-starred with Bette Davis, saved the day by refusing to make the picture unless Bogart played Mantee (as he had done opposite Howard a year before on Broadway). The DVD commentary claims that Bogart’s performance as Mantee saved his career, was the talk of the lot, and bowled over the bigshots at Warners. You have to wonder what they were thinking when you look at the movies Bogart made at Warners between The Petrified Forest and High Sierra (1941). The five years of mostly unworthy roles he had to endure after the supposed “breakthrough” says a lot about the slave-trade aspect of the studio system.

Bogart in Hell

Bogart was only slightly exaggerating when he told an interviewer, “In my first 34 pictures, I was shot in twelve, electrocuted or hanged in eight, and was a jailbird in nine.” Roles like those were actually closer to purgatory than hell because in most of them he was at least performing in the tough-guy milieu he would dominate so brilliantly in the 1940s and for all time. If you want to see Bogart in hell, wait for Turner Classic Movies to show Isle of Fury, probably the worst of the movies he made after The Petrified Forest.

In Isle of Fury you have Bogart without shadows, bereft of even his snarl, so small, so civil, so social; Bogart in white shirt, pants, and shoes, with the stigmata of a neat little mustache; Bogart, who pales beside even so unworthy a male as square-jawed, wooden Donald Woods; Bogart the unwitting cuckold, whose particular level of hell is a South Seas port where he oversees a fleet of native pearl divers who are afraid to dive because other divers have gone down and never come up. The only way Bogart, whose name is Valentine Stevens, can convince them to get on with it is to dive into those mysterious waters himself. Not being a pearl diver, he has to submit to enclosure within a laughably bulky diving outfit complete with a bulbous helmet that his wee mustached face peers miserably out of as they drop him overboard. Plodding underwater, he soon discovers the mysterious menace, the evil force, is an octopus. But this is no high-tech Hollywood octopus such as today’s digital wizards might create. This is an over-sized Muppet Octopus the Warners art department must have cobbled together out of pipe cleaners and licorice sticks. Bogart never had a chance. In symbolic terms, he was trapped and Warners was the octopus.

Not to worry. He’d paid his dues and one day four years later when the current king of the lot, Paul Muni, was on a leave of absence, the Warners brass decided, in effect, that it was time to make Bogart a star. After George Raft turned down both High Sierra and The Maltese Falcon, Bogart had his ticket to movie heaven, with Casablanca and Lauren Bacall waiting just around the corner.

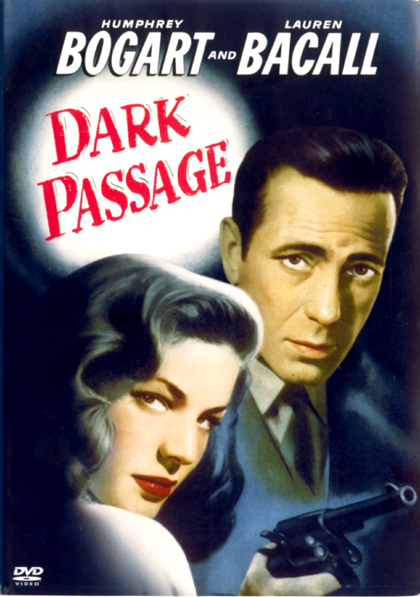

Dark Passage

Since I seem to have fallen into the habit of ringing out anniversaries of years ending in “7,” I’ve got an excuse to celebrate one of my favorite Bogarts, a movie Pauline Kael inexplicably and unceremoniously panned (“a bummer … an almost total drag”). Dark Passage (1947) is not only one of the best film noirs ever made, it offers a cozier, more domestic version of the on-screen relationship of Bogart and Lauren Bacall than the more famous pairings in To Have and Have Not (Bacall’s unforgettable 1944 debut) and The Big Sleep (1946). Bogart is not playing a private eye this time but a man framed for the murder of his wife who escapes from San Quentin and sets about finding the real killer. His savior, played by Lauren Bacall, puts him up, gets him some clothes, and, of course, falls in love with him. The thing most people who have seen Dark Passage remark on is that for well over half the movie we don’t even see Bogart. We hear his voice and we see through his eyes until Bacall peels the bandages off his face after an affably sinister plastic surgeon skillfully alters it in a scene that belongs in the Film Noir Hall of Fame. Though the picture begins in broad daylight with location shots of San Quentin, the Golden Gate Bridge, and San Francisco, it might as well be pitch black because when Bogart speaks, it’s always after midnight.

Thus has the clean-cut fellow who sounded like a sedated Bugs Bunny in Up the River become the legendary man of shadows haunting the city that never sleeps. In 1947 he’s also king of the lot, the highest paid movie star in Hollywood, and he’s getting all that dough for a part where he doesn’t even show his famous face until the last hour. And since Bugs himself is another of the reigning Warner Bros. stars, the DVD of Dark Passage offers the bonus of a cartoon where Elmer Fudd attempts to catch the wascally wabbit so he can serve him up to a cartoon version of Bogart. Bugs resists with his usual lunatic finesse until a cartoon Lauren Bacall sits down next to Bogey. At that point the ever randy Bugs offers himself to the couple on a platter.

Ten years after he made Dark Passage, in January 1957, Bogart died and the legend was born. The films Bogart made in movie heaven (and even a few from purgatory) are available on DVD at the Princeton Public Library.