|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 39

|

|

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

|

He steals what he loves and loves what he steals ….

Dylan shuffles space and time like a man dealing stud poker. One moment it’s 1935, high atop some Manhattan hotel, then it’s 1966 in Paris or 2000 in West Lafayette, Indiana, then it’s 1927, and we’re in Mississipi ….

Sean Wilentz on Bob Dylan

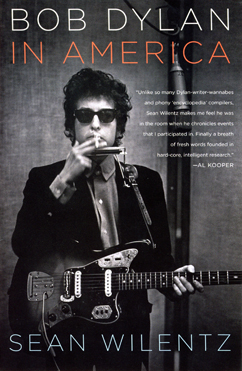

Sean Wilentz’s Bob Dylan in America (Doubleday $28.95) does what any worthy book about a great musician should do. It sends you to the music. And, as Al Kooper, who was there, points out, Wilentz puts you “in the room” during the making of Blonde on Blonde, an album no one needs to send me to. I go there on my own at least once a year.

If your knowledge of pre-electric Dylan (and American folk music in general) is scattered and sparse, Wilentz’s book will show you the way to songs you should know better, as happens when he contrasts the Beatles, “with their odd chords and joyful harmonies,” to “the long-stemmed word imagery in ‘Chimes of Freedom.’” Long-stemmed words? What’s that about? Go to the song and you’re amazed and a bit shamed to realize you never really heard it, never appreciated that Dylan doesn’t hear the chimes, he sees them, and he sees them flashing. Read the lyrics out loud to yourself and you understand why Allen Ginsberg recognized Dylan as a master.

Hattie Carroll

Then there’s the song Wilentz calls “a surpassing work of art” whose “lyrics, like its outrage, are completely under control.” The only way I can find “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” at two in the morning is to search for it on YouTube, where it can be experienced in a somewhat murky black and white video set in a rustic interior that resembles a log cabin in the Great North Woods. You hear Dylan’s harmonica before you see him, as the camera pans over the other occupants of the cabin, all male, each one solemnly absorbed in some ordinary activity, one smoking a pipe, one playing solitaire, another reading the paper. They have the look of hunters, outdoorsmen, or maybe they’ve kidnapped Dylan and the one who’s writing with such concentration is at work on a ransom note. The strangest thing is that they seem to have little or no awareness of the music and its message. They’re not really listening so much as inhabiting the atmosphere of the song being sung with such quiet passion by a very young Bob Dylan, so young he might have just arrived from Hibbing, or maybe this is Hibbing in the dead of winter. According to YouTube, the year is 1963 and Dylan is 23 (he looks 15).

Come to this moment 47 years later with an awareness of the music made by the same man at 60 in the first decade of the new millennium and you’re in what Wilentz calls “the magic zone where it was 1933 and 1863 and 2006 all at once.” Addressing the complaints about Dylan’s magpie tendencies in Love and Theft and the three albums of new old music that followed it, Wilentz goes on to say that “Quoting, without credit, bits of a Henry Timrod poem or adapting a Bing Crosby melody was not, by these lights, an act of plagiarism, and it involved more than recycling the forgotten. It was part of an act of conjuring.”

In that odd backwoods scene conjured, staged and filmed by the Canadian Broadcasting Company for “Hattie Carroll,” it’s easy to imagine that the drunken, thoughtless killing of a kitchen maid by a wealthy 24-year-old white tobacco farmer — the incident the kid from Hibbing has clipped from the newspapers, reimagined, and is singing about — took place in the 19th or early 20th century when in fact it had happened in February of 1963, the same year Dylan wrote the song. And when you hear that it happened at a “hotel society gatherin’” in Baltimore, it’s hard to keep your thoughts from jumping ahead to the mid-2000s and The Wire, the television series set on the mean streets of Baltimore and peopled by the descendents of Hattie Carroll. You know Dylan’s song had to be in the minds of the makers of that urban epic, and sure enough, a search online reveals that the program’s creator, David Simon, actually interviewed Hattie’s killer, William Zantzinger, the man Dylan has immortalized in eternal infamy and who died unrepentant in 2009, in Baltimore.

New York the Muse

So how is it that a unique book being misleadingly reviewed as a biography has been produced by the Princeton University history professor best-known for works like The Age of Reagan (2008) and The Rise of American Democracy, which won the 2005 Bancroft Prize?

“Only a few hints — a few diffused, faint clues and indirections.” The gist of the line from Walt Whitman that serves as Wilentz’s epigraph is implicit in his introduction when he says that writing a book about Dylan “wouldn’t have been in the cards except for a fluke, the result of strange good fortune.” Indirections or no, the “good fortune” happened to be that his father was Elias Wilentz, co-owner with Ted Wilentz of “Greenwich Village’s Famous” Eighth Street Bookshop. Besides being a literary center, as key to the New York counterculture as City Lights was to San Francisco’s, the Eighth Street had its own imprint, Corinth Books, which published works in paperback by Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Leroi Jones, Charles Olson, and Frank O’Hara, among others in those busy first years of the 1960s. Presumably still more important to the future historian was Corinth’s American Experience Series, the publishing venture overseen by his father, with reprints of texts on subjects such as exploration, Native Americans, the New World, black experience (a book about Harriet Tubman), and a facsimile of The Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex (Melville used the original when researching Moby-Dick). Is it any wonder that a child who grew up in that environment would one day become a student of American Studies?

In the course of examining the diverse influences encompassed by his subject, Wilentz has in effect written a shadow memoir haunted by his father and the bookshop where Uncle Ted introduced Bob Dylan to Allen Ginsberg in his apartment above the store one day. New York was where it came together for both Wilentz and Dylan, who signaled his own debt to the city with the cover photograph for his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, and his 2006 album Modern Times. As Wilentz shows, particularly in the opening chapters, New York City was both source and muse for Dylan, whether in the New York Public Library, the streets and cafes of the Village, in the art cinemas where he first saw Les Enfants du Paradis (another fascinating influence, like that of Aaron Copland, unearthed by Wilentz), or in the studios of artists like Norman Raeben, whose teachings figure in one of Dylan’s greatest songs, “Tangled Up in Blue.”

The Lone Pilgrim

Within the New York manifestation of that “magic zone” of timeless connection and creation, the event that first brought Wilentz and Dylan together is the October 31, 1964 Philharmonic Hall concert, a bootleg recording of which Wilentz would write Grammy-nominated liner notes for some 40 years later. While the concert is fully covered in Wilentz’s third chapter (“Darkness at the Break of Noon”), the first mention of it in the introduction echoes the “strange good fortune” that led to this book: “It was another bit of luck: my father got hold of a pair of free tickets.” So, it was at the age of 13 in the company of his father, thanks to his father, that the son found the subject he would take up almost half a century later.

When Dylan’s career faltered in the 1980s, so did Wilentz’s attachment. Everything changed with World Gone Wrong, the 1993 album containing the performances Wilentz called “Dylan’s field recordings of himself.” Although Wilentz’s book is not dedicated to his father’s memory, it might as well be. The depth of the association with Dylan’s music is apparent in Wilentz’s admission, first made in the introduction, that Dylan’s rendition of “The Lone Pilgrim,” a ballad whose lyrics date back to 1838, helped him grieve when his father died in 1994. Listening to the song “over and over” during the months after his father’s death brings “a solace that came from the last place, and the last performer, I’d have expected it from. More than a decade later, it still brings solace, especially in the last two lines and the very last word, which is also the last word on World Gone Wrong, ‘The same hand that led me through scenes most severe/Has kindly assisted me home.’” For Dylan’s performance Sean Wilentz “will always feel a gratitude that is completely personal.”