|

|

Vol. LXV, No. 14

|

Wednesday, April 6, 2011

|

I go among the Fields and catch a glimpse of a stoat or a fieldmouse peeping out of the withered grass — the creature hath a purpose and its eyes are bright with it — I go amongst the buildings of a city and I see a Man hurrying along — to what? The creature hath a purpose and his eyes are bright with it.John Keats, from a letter to his brother in America

Poised, bright with purpose, 169 book stoats and field mice, counting myself (number 169), are lined up as if for a school fire drill. It’s preview day — or, some would say, dealer day — at the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Book Sale. At the stroke of ten, the tensely civil, tenuously constrained line moves down a long hallway into the school gym. By the time I get there the dealer creatures are sweeping the book-laden tables and plunging this way and that, arms teeming with spoils. Their eyes may be bright with purpose but their moves are random and reckless as they careen about searching for fresh veins of resalable printed matter. It’s only five past ten and already the tables look blitzed and huge piles of books have been claimed, shrouded, held hostage until the dust clears and there’s time to check the cost, the provenance, and the condition. Meanwhile, all around the wary browser is an incessant beeping noise like the beep beep beep of lifeline monitors in the ER. It’s the sound of scanner creatures scanning value on the net via ISBN numbers. Welcome to 2011.

In the letter quoted at the top, Keats was contemplating how far he and mankind are “from any humble standard of disinterestedness.” Were he witness to what goes on in the first hour of this sale, all these fiercely focused people scurrying around, the adrenaline so thick you could cut it with a knife or take it in your arms and dance with it, maybe he’d see evidence of the “electric fire in human nature” that tends to bring about “among these human creatures … some birth of new heroism,” but I doubt it. As he says in the next sentence, “the pity is that we must wonder at it: as we should at finding a pearl in rubbish.”

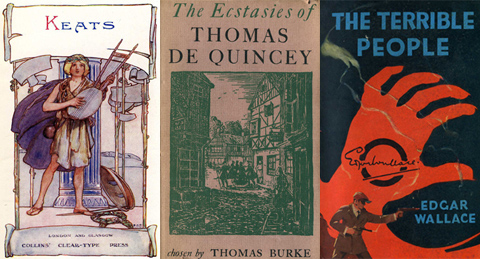

Isabella Abandoned

Speaking of pearls, when I stop to look over the cast-offs on a table marked for dealer discards, I notice a colorful little volume not much larger than your average iPhone. The vine-bordered cover says ISABELLA in gold letters and under it in blue letters KEATS. Priced at $1, it’s just the sort of puny, fated-to-be-neglected item a dealer in a hurry would toss aside. The endpapers are a miniature pastel mural showing swans, a half-naked mythological being with immense wings and a goddess with arms like a stevedore’s and amber hair streaming down to her hips. On the title page is a hapless looking lad playing a lute opposite a frontispiece picturing Isabella in Renaissance Florentine finery dementedly hugging her pot of basil. The page edges are trimmed in gilt. On one of the pastel-shaded plates inside, Fancy is portrayed as a barefoot, flower-bearing goddess with a stern, beautiful, severely intelligent face. It’s Fancy as Jane Austen might have imagined her.

The main attraction, of course, is the poetry, each poem titled in red letters and headed by black and white images of landscapes and seascapes. It’s a somewhat unorthodox selection, with lesser known pieces like “Calidore” and “Robin Hood” keeping company with more illustrious works such as the title poem, both “Hyperion” fragments, all the great Odes save “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” but no “Bright Star,” no “La Belle Dame Sans Merci,” no “Eve of St. Agnes.”

A small maroon book plate buried in the pictorial undergrowth of the endpaper reads Arthur Tyer/7 Uxbridge Rd./Broadway, Ealing. Street names like Uxbridge Road set me thinking of 221B Baker Street. I can almost hear Mrs. Hudson announcing “It’s a Mr. Tyer from Ealing, Mr. Holmes.”

After a little detective work of my own using some 21st-century technology, I find Arthur Thomas Tyer in the National Archives, in possession of a 21-year lease from 24 June 1885 with a Mr. Charles Henry Woods, both of 4A Broadway, Ealing, booksellers and stationers. Their shop and garden cost them £115 yearly for first year, £120 yearly for second year. One wonders what happened to Woods when Tyer moved to Uxbridge Road. Did they fall out? Did they move together or did Woods die (preferably under mysterious circumstances)? The real mystery is how a human chain of book dealers and book buyers helped this none too sturdy little volume make its way from Mr. Tyer’s bookshop on Uxbridge Road to the Princeton Day School gym in 2011.

Walking With DeQuincey

More London associations came into play when The Ecstasies of Thomas DeQuincey showed up in the relocated, roomier Collector’s Corner. The attraction of the volume was its picturesque dust jacket, its title, and the fact that the “ecstasies” had been “chosen by” Thomas Burke, a spiritual intimate of the Opium Eater. In fact, DeQuincey and Burke share the same down-and-out-in-London subject matter. While DeQuincey’s special province is Soho and Marylebone, the author of Limehouse Nights covers the East End and the docks.

Burke’s enlightened sympathy for his soulmate makes his introduction to DeQuincey’s Ecstasies a work of art in itself and well worth the nine dollars I paid for the book. Burke imagines that “if DeQuincey’s ghost walks at all,” it walks “under the million dreamy windows of midnight London.” So susceptible was Burke to the enchantment of the Confessions that “thereafter in all my wanderings he walked at my side, more positive to me than any of the living bodies that jostled about me.” Even so, Burke’s DeQuincey remains unknowable, a fog-shrouded shadow being, “a goblin; a furtive, flitting creature whom nobody ever saw …. All his life he wanted to hide.”

My own most memorable encounter with DeQuincey took place on a bus between Tehran and Baghdad where, as night fell, I was reading “The Glory of Motion” after smiling over a prefatory passage about the time one of his daughters came into his study to find him calmly reading a book with his hair on fire. At the time it seemed miraculous that the Macdonald Illustrated Classics edition of Confessions of an English Opium Eater (its glassine wrapper still intact) would turn up in a Tehran street market, but as the peregrinations of Ayer’s copy of Keats demonstrate, what makes the world of books go round are the creatures who write and sell and read them and will continue doing so regardless of Kindles and Nooks.

“Never Heard of Him”

A multitude of potential buyers had been all over the Mystery tables without deigning to pick up, for a mere $2, The Terrible People (1926) by Edgar Wallace, with its spectacular dust jacket. Whenever one or another of this author’s 175 novels surfaces at book sales, which is often, they’re rarely wearing dust jackets. The dealers scorned the Wallace because it’s a reprint, and they passed up an immaculate, handsomely designed book of poetry from 1945 because they’d never heard of Hoyt Hudson. Chances are, neither have you. Hudson, who is not related to the landlady at 221B Baker Street (his middle name is Hopewell), was chairman of the Princeton University English Department from 1933 to 1942. When he died at 50 in 1944, friends and colleagues (he had since moved west, to Stanford) put together this collection of accomplished, if not great, poetry, called it Celebration and had it published by Grabhorn Press in a limited edition of 500 copies.

Look for Hoyt Hudson online and you’ll find an essay (“An Ignored Giant”) celebrating him as a scholar of rhetoric and singling out for special mention his essay, “De-Quincey On Rhetoric and Public Speaking,” which refers to “the teeming mass of DeQuincey’s ideas,” his “overflowing bounty,” and concludes: “So, the last word is, read DeQuincey.”

Our Hero

And read Keats, if not the poetry, the letters, or at least the installment from February 19, 1819 (online under “Keats on The Vale of Soul-Making”), which begins with the 24-year-old poet’s account of his ill-fated first time playing cricket (“I got a black eye … the second black eye I have had since leaving school”). In the letter I’ve been quoting from, which was begun on February 14 and sent in a series of packets to George and Georgiana Keats in America, the passage that begins “I go out among the Fields” ends with lines I quoted for an epigraph in a 2007 column about the letters (“Discovering Keats: A Birthday Celebration”):

“… I myself am pursuing the same instinctive course as the veriest human animal you can think of — I am however young writing at random — straining at particles of light in the midst of a great darkness — without knowing the bearing of any one assertion of any one opinion. Yet may I not in this be free from sin? May there not be superior beings amused with any graceful, though instinctive attitude my mind may fall into, as I am entertained with the alertness of a Stoat or the anxiety of a Deer?”