|

|

Vol. LXIV, No. 14

|

|

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

|

|

One after another they rise before me. Books gentle and quieting; books noble and inspiring; books that well merit to be pored over, not once but many a time. Yet never again shall I hold them in my hand; the years fly by too quickly, and are too few. Perhaps when I lie waiting for the end, some of those lost books will come into my wandering thoughts, and I shall remember them as friends to whom I owed a kindness — friends passed upon the way.George Gissing, The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft

One of the many charms of the Bryn Mawr-Wellesley Book Sale is the element of surprise. With as many as 80,000 volumes on the tables (according to one weary volunteer), you never know what you’ll be bringing home. When I set out last Wednesday, I had no earthly reason to meet up with Coventry Patmore. But who could resist a book of poetry from 1856 called The Angel in The House by a man with a name like an English village? And for only $2.

Nor was I able to resist, also for a mere $2, Charles Williams’s All Hallows Eve, which begins “She was standing on Westminster Bridge. It was twilight, but the City was no longer dark.” With an introduction by T.S. Eliot and that opening image, I’ll take it home and give it shelter from the storm.

And over here begging to be bought is an old friend who wandered out of my library some years ago, Thomas Wolfe’s The Hills Beyond. Who better than the lonely giant from Asheville, N.C., to sound the theme at the bazaar of the Lost? The first story in this book of almost-lost pieces from the mountain of manuscript that became Look Homeward, Angel (originally titled O Lost) is “The Lost Boy.” Of course finding Thomas Wolfe at a sale of this magnitude is no surprise. I also had reason to think Walt Whitman’s Civil War journal, Specimen Days, might turn up, which it did, in a 1968 anthology of his prose (the Deathbed Edition). An item I’ve had my eye on for years — a piece of Princetoniana called Poe’s Run (with pictures by Booth Tarkington) — was finally marked down to an affordable price at Collector’s Corner, so here it is being sniffed at by Nora, one of our tuxedo cats. Though I like to pretend otherwise, the Poe of the title is not the author of “The House of Usher,” but a cousin, a football hero and one of the Old Nassau’s illustrious Poe brothers (“But while Grasse grows and Watere runnes/Princetowne shall have a Poe”).

The Big Find

There’s some poetic justice in the fact that the most expensive and evocative castaway that turned up last week was written by a man who has no peer when it comes to celebrating the precious essence of a book and the euphoria of the quest, a man who claims to know every volume he owns “by its scent,” who understands the difference between possessing a book and borrowing it from a library: “Now and then I have bought a volume of the raggedest and wretchedest aspect, dishonoured with foolish scribbling, torn, blotted — no matter, I liked it better to read out of that than out of a copy that was not mine.”

This is someone who remembers the time and place of each encounter with books “purchased with money which ought to have been spent on what are called the necessaries of life.” (that what are called says it all.) “Many a time,” he continues, “I have stood before a stall, or a bookseller’s window, torn by conflict of intellectual desire and bodily need. At the very hour of dinner, when my stomach clamoured for food, I have been stopped by the sight of a volume so long coveted, and marked at so advantageous a price, that I could not let it go.” He goes on to mention spotting one of those “long-coveted volumes” at an old bookshop in Goodge Street when six pence was all he had in the world, just enough for a plate of meat and vegetables at an Oxford Street coffee shop. So he paces the pavement, fingering the coins, “two appetites at combat” within him. And, no surprise given his concept of the true “necessaries of life,” he buys the book, takes it home, and settles for “a dinner of bread and butter.”

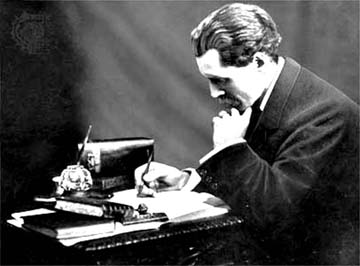

Is it any wonder then that George Gissing (1857-1903) has fascinated generations of writers, book lovers, and collectors? For besides having the underdog charisma of one who was down and out in London and survived to tell his tale, he expresses a love of books as few others have done, feelingly and at length, while giving us one of the most vivid pictures ever put in print of the harsh realities of the literary life and publishing — the subject of his best-known novel, New Grub Street.

The fact that most people reading this column have likely never heard of Gissing is close to the heart of his appeal. It’s as if one of those “mute inglorious Miltons” in Thomas Gray’s country churchyard had somehow fought his way through the miasma of obscurity to produce against all odds 20 books in 20 years, including a half dozen of the best novels of his time.

The book I found in Bryn Mawr’s Collector’s Corner for $20 appeared some 20 years after Gissing’s death under the imprint of Pascal Covici, the man who would later discover and publish John Steinbeck. The book is titled The Sins of the Fathers, after a story the destitute 20-year-old exile from the Midlands published in the Chicago Tribune, of all places. The three other stories, “Gretchen,” “R.I.P.” and “Too Dearly Bought” were also published in the Tribune at a time when “a few cents’ worth of peanuts” were all Gissing could afford to eat. It’s not stretching it much to say that the $18 he received for the title story, apparently his first publication, saved his life.

Vincent Starrett’s introduction to The Sins of the Fathers begins like a story itself: “In the twentieth year of his melancholy existence, George Robert Gissing, having involved himself in an offense against the law, was for a time imprisoned, then sent by his friends to America.” The details Starrett neglects to mention are that Gissing, despite being born into a lower middle-class family, had made a brilliant start in life at college in Manchester, until he fell in love with a prostitute, spent all his own money in an effort to keep her off the street, and eventually resorted to stealing to support her, for which he was arrested and served a month’s hard labor in prison.

The Story

In one sense, “The Sins of the Fathers” is the story of Gissing’s life: a young man helps a poor, desperate young woman “of the lower class” he meets on the streets of a “great English manufacturing town.” As much for sympathy’s sake as passion’s, he wants to marry her, but his father is against the match and to put it off sends him to America to earn the money to support a wife. In time the father deceives the girl with a forged letter and then deceives his son by claiming that she died. After marrying someone else, he spots the girl in the chorus of a musical, seeks her out, and pays for his good heart and his father’s sin as she drags them both down to death in the icy river. In “real life” when Gissing came back from America he married the prostitute, wrote and published his brilliant first novel Workers in the Dawn (a financial failure), supported his wife as she sank into alcoholism, except that rather than being dragged to an icy fate, he left her; even so, he continued to support her on the little he had until her death five years after they separated. His second wife was also of lower birth, met under circumstances that were much like those in the story; she had no sympathy for his work, the marriage was a nightmare, and she ended up in a lunatic asylum. Gissing’s third match, with a French woman who understood his work (she translated it in fact), finally brought him a few years of relative happiness. Anyone who has read The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft, Gissing’s elegaic imaginary journal (and the work from which I’ve been quoting), or any of his grittier, darker, more ambitious work, will know that his “melancholy existence” was brightened by his love of literature and music (Ryecroft mentions “that Nocturne of Chopin’s which I love best”) and the gratifying creative energy that produced all those novels, along with a travel book and a biography of Charles Dickens.

The other tale told in Vincent Starrett’s introduction to my Bryn Mawr find (number 530 of a limited edition of 550) testifies to the devotion of those to whom Starrett dedicates the book: “the collectors of the work of George Gissing...an increasing race.” Starrett himself and another collector named Christopher Hagerup burrowed into the files of the Chicago Tribune looking for the “lost stories.” Hagerup got there first, identified the tales (two of which had been unsigned), and “painstakingly copied them from the yellowed files with a stub of a pencil” (no easy chore: the published book is 124 pages long). After all that effort, Hagerup decided the tales were “not important enugh to justify publication.” That was Starrett’s cue. Aware of all the Gissing devotees who wanted to see the early work, he was determined put them in print, which he accomplished when Pascal Covici came along.

George Gissing died the same year he wrote the passage quoted above about the “lost books” that gently entered his last thoughts.

Gissing Reprints

Only one of Gissing’s novels, The Odd Women, is in the collection of the Princeton Public Library, although most of his best work has been reprinted in recent years. In fact, there were 32 editions between 1961 and 1977. The most recent biography, Paul Delany’s George Gisssing: A Life, was published in England in 2008. A fictional version of Gissing’s life is the subject of Morley Roberts’s The Private Life of Henry Maitland (1912). Gissing is also a character in Peter Ackroyd’s 1994 novel Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem.